Best Ways Older Workers Can Prepare for a Recession

How to help avoid becoming part of the long-term unemployed

If you’re over 50, employed and getting a little jittery about the safety of your job due to the cooling economy, that’s understandable. Although the unemployment rate is still just 3.7% — near its 50-year low — monthly job growth has slowed to 158,000, compared to 223,000 a month a year ago. And the 130,000 jobs created in August failed to meet economists’ expectations.

The overall slowdown in the U.S. economy, due to uncertainty over tariffs and trade policy, is prompting concerns about how much further things might decelerate in coming months.

Although the Federal Reserve Board is likely to reduce the risk of recession by cutting its benchmark interest rate a quarter point at its meeting next week, that won’t reassure many economy watchers. For instance, Ray Dalio, founder of the world’s largest hedge fund, just told Bloomberg News that he sees a 25% chance of a U.S. recession this year and in 2020.

What Happened to Older Workers in the Last Recession?

Here’s why this matters so much to older workers: In the last recession, it took much longer for unemployed people over 50 to get hired, on average, than for younger people without jobs. What’s more, the older ones were also more likely to become part of the long-term unemployed — out of work for six months or longer. And when they finally landed a job, their wages were typically much lower than in their previous one and below the level of their reemployed younger peers.

According to the Urban Institute research report, Age Disparities in Unemployment and Reemployment during the Great Recession and Recovery, nearly half of people age 25 to 34 who lost their jobs during the Great Recession were reemployed within six months. Yet it took more than nine months for half of the unemployed ages 51 to 60 to find work.

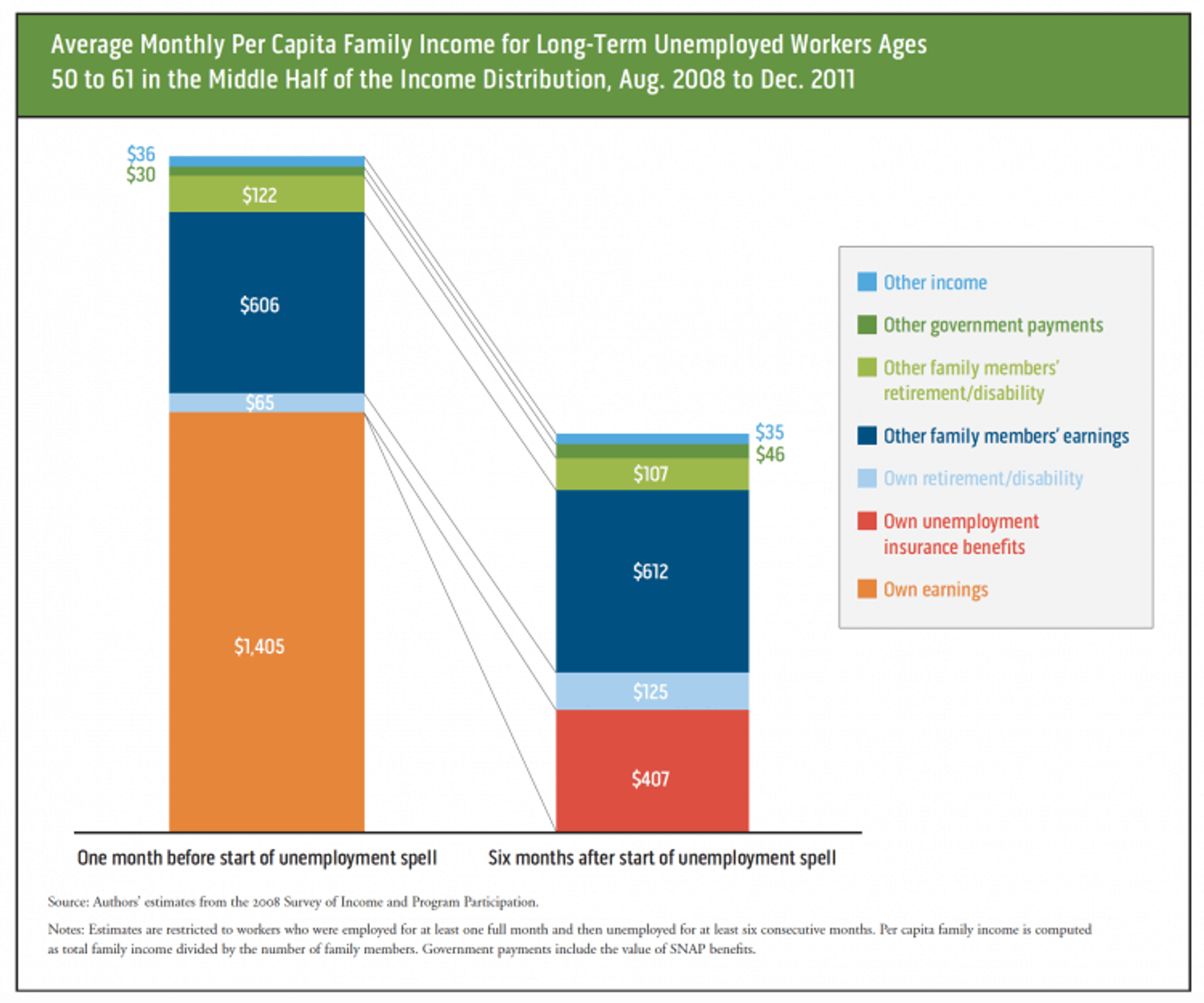

As the chart below indicates, long-term unemployed workers ages 51 to 60 also took a big hit to their monthly household income — a nearly 40% drop. That’s larger than other age groups since the 50s are typically peak earning years.

What About the Next Recession?

And for the next recession, whenever it may come…?

“I’m not particularly optimistic that things will be better for older workers,” says Richard Johnson, senior fellow at the Urban Institute and director of its program on retirement policy.

With good reason. A forthcoming article in Generations: Journal of the American Society on Aging will note that long-term unemployment has remained at heightened levels. More than one in four job-seekers ages 55 and older had been unemployed for more than six months in March 2019, it says; for those 54 and younger, one in five were.

“The labor market is brutal for older workers,” says Carl E. Van Horn, director of the John J. Heldrich Center for Workforce Development at Rutgers University and co-author of the article with Maria Heidkamp, director of the New Start Career Network at the Heldrich Center.

A combination of factors is at play. There’s age discrimination by employers, of course, but also the toxic stigma that often attaches to the long-term unemployed. Dismissive phrases like “There must be something wrong with him” or “It must be her fault she isn’t working.”

But, counters Van Horn, “These are people who are victims of acts of economic violence. There’s no more reason to stigmatize them than people who drive Hondas.”

Job-Protection Advice for Older Workers

So what should you consider doing now to help protect yourself and your job when the recession arrives?

An intriguing suggestion comes from Robin Johnson, lead trainer at CareerForce, Minnesota's career development and talent matching resource. She says: Practice looking for a job, but not applying for jobs. The value of this exercise is it acquaints you with what employers are looking for in their job postings. The effort also helps you focus on where you might look for work should that become necessary.

Another precautionary step: Pay increased attention to your network of colleagues, former workmates and acquaintances. Most job referrals these days come through personal networks and many people get hired after someone puts in a good word about them to the hiring employer.

Troubled by high rates of joblessness among those 45 years and older, Van Horn and colleagues at the Heldrich Center created the New Start Career Network in 2015 for older unemployed New Jerseyans. The motivating idea was to see if providing digital and human job counseling in a cost-effective way would help the long-term unemployed get work. New Start Career Network’s counselors are professional coaches volunteering their time.

“We have concluded that it can be replicated,” says Van Horn. “It is cost-effective. It supplements what is out there now.”

Among the lessons Van Horn learned from the New Start Career Network: Once you lose your job, don’t wait around to look for another. Try to avoid the unjust stigma faced by the long-term unemployed and get to work right away finding a new employer.

“You need to run scared,” Van Horn says. “Push yourself hard.”

Johnson echoes his advice. “You need to get serious,” she says. “No one likes looking for work. It isn’t fun. You need to show up for the process.”

Tapping into your network immediately is critical. But Van Horn notes that this step is often easier said than done. Losing a job is traumatic and, with networking, you’re supposed to openly tell people you’re out of work and looking for employment.

But it can pay off.

Van Horn tells the story of a lawyer he knows who was well-respected in the orthodox Jewish community and out of work. Van Horn asked him if he had talked to people in his temple. The man said he hadn’t, and Van Horn implored him to start. “I understand why he didn’t do it,” says Van Horn. “But he had to do it.”

After networking this way, the man got a job at a religious school.

Here’s the thing: The rise of the long-term unemployed doesn’t reflect individual failings. Losing a job could happen to any of us. And the evidence is overwhelming that individuals are willing to do their part to get work. Society, however, needs to devote more resources keeping people attached to the job market and knocking down barriers of age discrimination.

In the meantime, put together your action plan. Just in case.