OPINION: Why We Need a COVID-19 Memorial to Those Who Died in Long-Term Care Facilities

A renowned anti-ageist argues for it as a matter of justice

The cruelty of the COVID-19 era has stripped us prematurely of many matriarchs and patriarchs, of all races and ethnicities, who had the misfortune to live in long-term care facilities that could not, or would not, save their lives. They are now an utterly disproportionate 40% of the U.S. dead — already 100,000 people.

Already, specific memorials are emerging: my own city has placed stark rows of empty chairs in front of City Hall for all of Newton, Mass.'s dead. Eventually there will be many scattered memorials, less ephemeral — plaques in hospitals, say, like those in fire stations after 9/11.

But we need to honor our missing, lamented elders with a special permanent and national cenotaph [a memorial to honor a person or people whose remains are elsewhere] to them, as a collective. This is a matter of justice and solidarity.

We grieve with the families for their loved ones who merely needed some help with activities of daily life; who were managing disabilities or chronic illnesses or cognitive impairments with dignity; who came to nursing or veterans' homes to recover from operations or because they liked congregate living more than loneliness.

They should have died hereafter, their hands held by loving hands. They could have.

We may wrongly think they were too frail and too susceptible to the coronavirus, instead of recognizing that they could have been better protected by their state bureaucracies and the administrators of their facilities.

The monument we need would be beautiful and dignified, soothing and unifying.

The truth is: In some care homes notable for forethought and good will, residents never got infected. Or if some tested positive, more of them survived. Many others could have had longer and happier lives.

The Grief of Families

Instead, their families remain left with grief, shock and sometimes outrage at the ageist neglect and malfeasance that bereaved them. Reckonings and reform are not yet in sight.

The survivors feel isolated, unable to hold healing funerals. But Americans not so afflicted can empathetically share their grief, nationally and publicly.

On a sad landmark day in September, "Doonesbury" cartoonist Garry Trudeau had Mike Doonesbury ask, wonderingly, "How do we grasp the vast scope of what's happening?" and filled the Sunday strip with 200,000 dots.

One way to grasp the scope of the wrong done to those who died and those who will die in long-term care facilities is by erecting a monument especially to them.

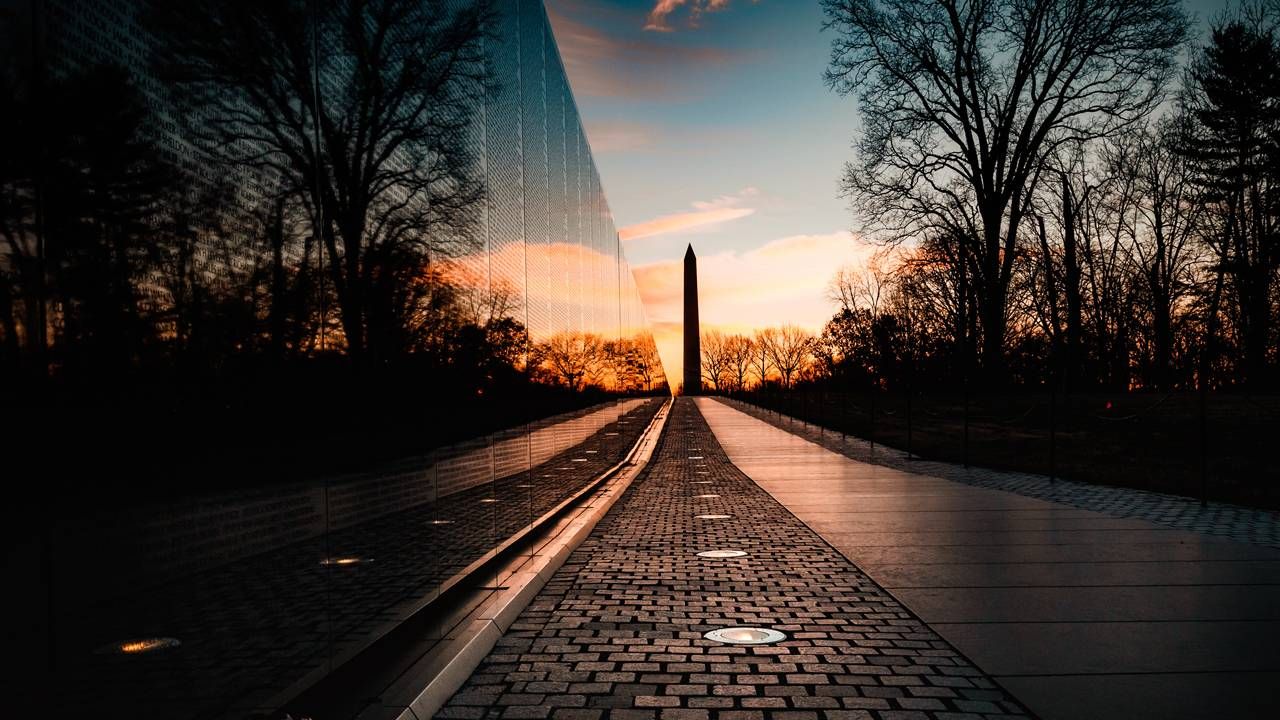

The monument we need would be beautiful and dignified, soothing and unifying. Imagine something that moves visitors like Maya Lin's Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington D.C. or the AIDS quilts. This one would be a noble structure of rich colors and materials to symbolize the way they are remembered, with full, individual lives and relationships.

Whatever the design, we need a powerful way of combating the terrible stereotypes of older adults who reside in care facilities: that they are unwanted and "demented" and therefore so much less than human that they are probably just waiting to die.

Aspersions against long-term care residents are cruel and untrue.

Ageism is intersectional and encompassing: into its vile attitudes and actions, it twists ableism and sexism, racism, classism and dementism.

Ageism in the Pandemic

Even before 2020, heavy foundations were laid for treating the prospect of older deaths without alarm or adequate funding for strict preventive measures. These attitudes led to a neglect that we can only call eldercide.

And since COVID-19, the statistics about the pandemic created a group identity for all older people as those-who-tend to-die. "The elderly" — including those of us who had until then thought of ourselves as still in the prime of life — were framed as doomed.

The first news of COVID-19 victims in long-term care facilities came from a nursing home in Seattle in February, and the statistics after that never let up. Certain ones were endlessly repeated: the median age of the dead; the higher risk of those in their 60s, 70s, 80s or beyond.

Our Commitment to Covering the Coronavirus

We are committed to reliable reporting on the risks of the coronavirus and steps you can take to benefit you, your loved ones and others in your community.

Read Next Avenue's Coronavirus Coverage

The numbing numbers cramp those of us in the second half of life into a faceless, sexless mass, without a voice. No one can "say their names." No one can even learn their gender or race. They did not only die; their selfhood was obliterated.

Journalists who've covered long-term-care facilities during the pandemic have tended to interview their administrators, aides and family members, instead of listening to survivors who were quarantined, isolated, lonely, perhaps terrified. Those witnesses, too, were silenced.

To Redress the Wrongs

The 100,000 who died have thus become a category of unmournable bodies. Grieving is human, but who is worthy of grief is something we learn. The process of mourning, or reform, or prevention, cannot even begin if the group in question is considered of less worth than other human beings.

#BlackLivesMatter is the response to one such deadly construction, based on a long history of racist othering; othering is the universal context of discriminations. The BLM demonstrations brought out white people and people of color who want to rid the country of the stereotype that young black lives lost were unworthy of grief.

Let us — our whole society — learn to defy ageism.

#OldLivesMatter is the slogan that can help our society once again think of all older adults as individuals with an equal right to life, wherever they reside, whatever their physical or cognitive or economic conditions.

And Congress and the president must reform long-term care so it provides the safe and comfortable homes we all deserve, if we are lucky enough to age toward old age.

Emily Dickinson told us how hard it is to mourn for strangers. She thought only "Immortal Friends" could provide that "vital kinsmanship:"

Bereavement in their death to feel

Whom we have never known

A Vital Kinsmanship import

Our Soul and theirs — between—

Let us — our whole society — learn to defy ageism. Let us begin to show solidarity with its victims. Thus we may prevent another eldercide. One way forward is to seek out the artists and architects who can turn our better knowledge, higher values and worthier feelings into a durable witness that rises up visibly and permanently from the earth.