How My Parachute Took 75 Years to Drop in Normandy

After storing a WWII parachute in our Brooklyn basement for decades, I recently began a quest to find a new home for it

While grounded during the pandemic, one of my projects was to find a worthy recipient for a red World War II nylon/cotton parachute that had been sitting in my Brooklyn, N.Y. basement for 22 years. In September, I traveled to visit its new home — at the site of a famous D-Day battle in Normandy.

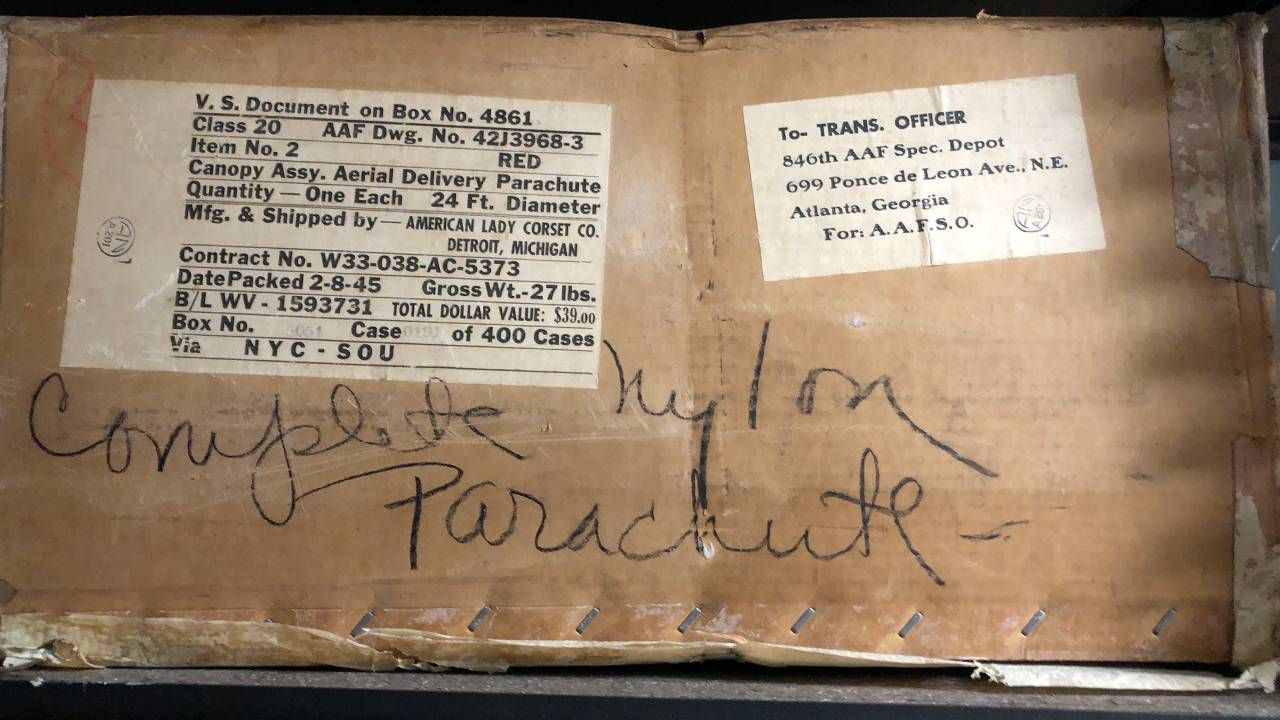

The parachute, in its original carton and never used, was previously in the attic of my parents' house in the Bronx when they bought the place "as is" in 1967. About a year after my father died in 1997, my mother sold the house and, while cleaning out 30 years of detritus, showed up on my stoop with this bulky, 27-pound bundle.

Though many people associate World War II parachutes with ones used by paratroopers or airmen, color-coded parachutes like ours were used for supply drops.

She announced that she was passing the torch to me, to preserve the parachute "for history." Envisioning the day when we, too, might need to downsize, my husband and I recently decided it was time to hand off our red inheritance to the pros.

Having spent five autumns in France during the past six years and visited many military museums (including some at the D-Day beaches), I've lingered at showcases of objects that have been used to tell the story of World War II. So, I contacted several museums that might, for various reasons, want to add our parachute to their collection.

A French Museum Shows an Interest

The one that showed the greatest interest was the Airborne Museum in Sainte-Mère-Église, the first French town liberated by the Allies on June 6, 1944.

"It is a very beautiful historic piece and its packaging is very pretty," wrote the museum's curator, Eric Belloc, in response to the photos I sent.

He was referring both to the parachute and the descriptive information printed on its carton: "red; 24 feet in diameter; manufactured by the American Lady Corset Company in Detroit; and valued at $39." It had been packed on February 8, 1945; the war in Europe ended three months later.

Though many people associate World War II parachutes with the white or camouflage canopies used by paratroopers or by airmen who bailed out of planes, color-coded parachutes like ours were used for supply drops.

Red signaled that an attached container held ammunition or weapons. Yellow was for medical equipment; blue for food; green for radios and white for other equipment. Though our parachute only got as far as a military supply depot in Atlanta during the war, it was the kind that had been used to deliver supplies to Normandy.

Sainte-Mère-Église was an important part of the June 1944 D-Day landing plan because a national road, known as the N-13, ran through it. Allied troops needed to control that road to move inland through German-occupied France after a coastal landing.

Thinking About D-Day

American parachutists of the 82 and 101 Airborne Divisions were assigned to capture Sainte-Mère-Église to secure the beachhead at Utah Beach to the east, where American troops were scheduled to invade by sea. Hollywood would later portray this strategy in the 1962 film, "The Longest Day," with a star-studded cast that included John Wayne, Henry Fonda and Richard Burton.

"Will you ever take it out of the box?" I asked. "No," Belloc replied, half joking. "Have you?"

Our drive to Sainte-Mère-Église, from an Airbnb about 50 miles inland, took us along country roads overhung with hedgerows — tall, dense bushes that provided the Germans with natural cover and impeded the advance of Allied troops after D-Day.

We approached Sainte-Mère-Église along the N-13, and parked in front of the church where American paratrooper John Steele got caught on the tower during the D-Day attack. (Though a dummy of him hangs there today, in real life he was taken prisoner by the Germans but managed to escape and continue fighting.)

The Airborne Museum, housed in various parachute-shaped buildings, was across the street.

Opened in 1964, the museum has expanded its collection through public and private donations. On view in one pavilion is a C-47: a military transport plane that dropped parachutists during the D-Day attack. In another, visitors can walk through the only original Waco glider on display in Europe; these fragile-looking structures, made of steel, wood and canvas, were used to transport troops and equipment across the English Channel and quietly deliver them behind German lines.

The Airborne Museum owns about 50 parachutes, Belloc told me when we returned the week after our initial visit to meet with him and Magali Mallet, its director. The most recent parachute donated, in 2013, came from Henri-Jean Renaud, who was 10 when he retrieved a used camouflage canopy from a nearby field in June 1944. His father, Alexandre, was the mayor of Sainte-Mère-Église at the time.

What the Curator Asked

Our parachute arrived in Normandy 75 years later. And when Belloc emerged from his office carrying the carton that had sat in our basement for more than two decades, I experienced a frisson of excitement.

"Will you ever take it out of the box?" I asked, as the four of us sat around a conference room table, examining it.

"No," Belloc replied, half joking. "Have you?"

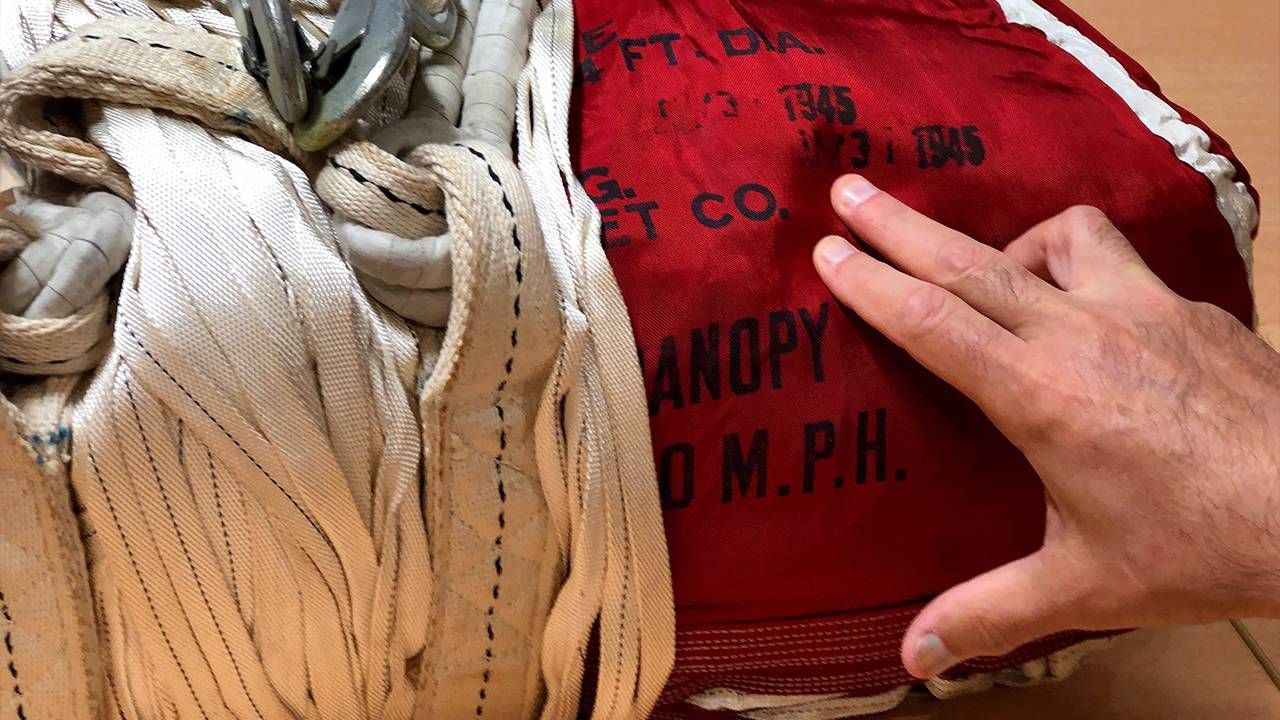

We hadn't, not wanting to do anything to diminish its historical value. So, except for the patch of red poking out of the thick, torn, brown-paper liner, we could only imagine what the parachute looked like.

Belloc offered to satisfy our curiosity.

Expertly, he slid the parachute out of its carton and unwound the white harness wrapped around it. He pointed out the clips that would have been used to attach the parachute to a matching supply container, like one we'd seen on display at the museum.

But unlike that object, which had faded to pink, our parachute was still a rich crimson. The heavy cardboard carton, and storage in dark areas, had kept it in perfect condition, Mallet said.

This was the first parachute the museum had received in its original box and the first made by the American Lady Corset Company.

The Lingering Mystery of Our Parachute

Though satisfied that we had done our part for history, we hadn't solved the mystery of how the parachute wound up in the attic of my childhood home.

My best guess was that it was purchased as surplus. WWII products that weren't needed (in this case, because the war ended) were auctioned off in bulk and otherwise sold as surplus. I was familiar with this concept growing up because there was an Army-Navy surplus store I passed by every day in my commute to high school.

My parents had bought their house from an estate, and the previous owner seemed to have been an eccentric pack rat. She was also a lawyer and active in Republican politics. Kimberly Guise, a curator at The National WWII Museum in New Orleans speculated that someone might have given her the parachute to hold for them because she had a large attic, and just forgotten about it.

Perhaps our original parachute owner might have planned to make an evening gown out of hers. Who knows?

After the war, it was popular to fashion used parachutes into other items. One newspaper ad for surplus white parachutes that the New Orleans curator sent me suggested they be dyed and used for everything from pajamas to evening gowns. So, perhaps our original parachute owner might have planned to make an evening gown out of hers. Who knows?

Red parachutes, like the one we donated, were produced in much smaller quantities than white ones, and therefore would have been a rare commodity.

As for its manufacturer — the American Lady Corset Company — none of the experts I spoke with were familiar with that business' wartime role. Its mostly female staff left their mark in labor-law annals by unionizing in 1940 and picketing the following year, with corsets worn over their street clothes.

After that, they apparently joined so many other women in the workforce who pivoted into the war effort. As Guise observed: "The confines of the corset and the opposite use of the parachute is an interesting juxtaposition."

The Airborne Museum plans to keep our parachute in storage for two or three years until the museum completes a renovation of its Waco Pavilion.

At that time, the parachute can't be displayed fully opened, Mallet told us, because parachutes "are too big and would lose their shape." But it could be exhibited, in a special case, partially unfurled, with the original carton beside it.

We found that prospect thrilling.

Not wanting to make any demands (or even suggestions), we told Belloc that we didn't care how the museum used our parachute. But knowing his plans satisfied every secret wish. This meant that as many as 100,000 visitors per year would see our parachute. And finally, it would be out of the box.