Never Pay the First Medical Bill You Get

Essential advice for patients from a health care investigative reporter

It wasn't until 1993, at Washington D.C.'s Georgetown University Hospital, that I began to fully appreciate the complexity of America's health care system. Life magazine had devised a clever photo shoot to document all 100+ people who were reflected in some way in the bill for ONE heart surgery: a double bypass/heart valve replacement on a 64-year-old retired teacher. I was there as an ABC producer to capture the moment for a "Nightline" episode, "The Anatomy of a Hospital Bill."

Front and center before the photographer were the recovering patient, sporting a surgical scar down his chest, and the chairman of surgery who'd performed the operation. Around them: dozens of nurses, pharmacists, the priest who prayed with the patient before and after surgery, plus the janitors, electricians, security guards and food service workers who kept the hospital running. Plus, of course, the administrative staff who compiled the bill — a lengthy computer printout totaling nearly $64,000.

When you talk to experts who review medical bills for a living, they will tell you that almost every medical bill has some kind of an error.

In a moment of candor, a hospital finance department official told us "the bill is largely fiction" and that "most hospital bills are routinely marked up higher than the actual cost."

Nearly three decades later, ProPublica investigative health care reporter Marshall Allen, author of the new book "Never Pay the First Bill (and Other Ways to Fight the Health Care System and Win)" says things haven't improved. He's been covering the industry for 15 years.

Allen likens today's health care system to a bully, squeezing and taunting the consumer. These days, he says, you don't need to have a major surgical procedure to feel the way steep out-of-pocket health care costs (including annual health insurance premiums and deductibles) and an epidemic of billing mistakes are draining your wallet. They're why 1 in 6 Americans wind up in medical debt collection.

Year after year, Allen notes, the cost of basic health care is Americans' No. 1 financial concern. His view: It's time to say enough is enough.

I spoke with Allen about how the nation's medical system got so out of whack and what patients can do to protect themselves from inaccurate, excessive fees:

Next Avenue: What changed in American health care that convinced you it was time to write this guide on how to fight back?

Marshall Allen: I think it is the perennial increase in the prices. Let's look at 2010 to 2020. Workers' earnings went up twenty-seven percent, family health care premiums went up fifty-five percent and deductibles went up a hundred and eleven percent. So, family premiums went up twice as fast as workers' earnings.

Curious, I got my ProPublica pay stubs from 2012 to 2019. And I could see that my premiums were going up so high while my coverage was getting reduced. If my premiums would have gone up at the same rate of inflation, I would literally have sixteen thousand dollars more in my pocket over that eight-year period.

And that's why you say some people feel as though they are uninsured, even if they are technically insured, because they're responsible for so much out-of-pocket.

Yes. Especially if someone's got a high [annual] deductible. It's common now to have a three-thousand-dollar, five-thousand-dollar or even ten-thousand-dollar deductible. That means you're functionally uninsured.

I can see the bill collection agencies smiling when they see the title of your book because they make money when people don't pay their medical bills. Are there times when you really shouldn't pay the first bill you receive from the doctor, clinic or hospital?

My point with the title is not that we should not pay our bills at all. But I argue that we should never pay the first bill until we have checked it to make sure it's accurately priced and accurately documented.

When you talk to experts who review medical bills for a living, they will tell you that almost every medical bill has some kind of an error. It's common for there to be charges for things that didn't even happen. And it's very common to be charged more than you should for something that did happen.

As you were writing the book, the issue hit home with a series of mistakes in your father's care at an assisted living facility — a medication error that worsened his dementia and the facility ignoring your mom's directive that he only be treated by his primary care physician. Then, you and your brothers had to struggle to correct the bill. How typical is this story?

Sadly, I think it is incredibly typical for the concerns of patients to be dismissed.

In America, we say the customer is always right. But in health care, the insurance companies are more concerned with keeping the hospitals and doctors and nursing homes and others in their networks than they are making sure that we're satisfied with the quality of care or the accuracy of the billing. So, even if you have an error in your bill, your insurance company will just pay it.

You really get this feeling that you're on your own.

And I think that's the sense of betrayal that the American public feels. Older Americans taking care of their older parents have experienced it — every year, higher and higher costs…

And so that's why there's this momentum building to do something. It's going to be a fight. There's going to be winners and losers, because right now they're taking away more of our money than they should and they're not going to release their grip on our money without us fighting back.

Among the mistakes in your Dad's case is that the billing code was Level Five — the most intensive, costliest exam. And this exam occurred soon after he had a full exam by his primary care physician before he was admitted to the assisted living facility. Was this an example of upcoding — billing for a more expensive exam than either was warranted or perhaps done? And how common is this practice?

Upcoding is extremely common. It's an epidemic. And I think it's the most common type of accepted fraud that's in our system right now.

How are patients starting to fight back against incorrect bills?

People are using small claims court to defend themselves. And it's our constitutional right to protect ourselves in small claims court against predatory practices of companies and individuals who take advantage of us.

Unfortunately, our health care system — especially the hospitals — have some of the worst offenders.

When you and your brothers jumped in, you had expertise in the health care system and your sister-in-law is a nursing home administrator with specialized knowledge. Is it realistic to expect lay people, especially older people who are wronged by the system, to successfully fight back? Isn't it often better to hire a professional patient advocate if you can?

I think that's often a great idea. You will have to pay the patient advocate a fee, but they are worth their weight in gold.

Yes, the average person may be intimidated to fight back. But let's just say five percent — even one percent — of the people are courageous enough to sue in small claims court. That would be like an army.

You'd have millions of Americans filing cases against hospitals for unfair bills. That would be a game changer, creating hassle and expense for the hospitals and giving them the incentive that they need to treat us fairly.

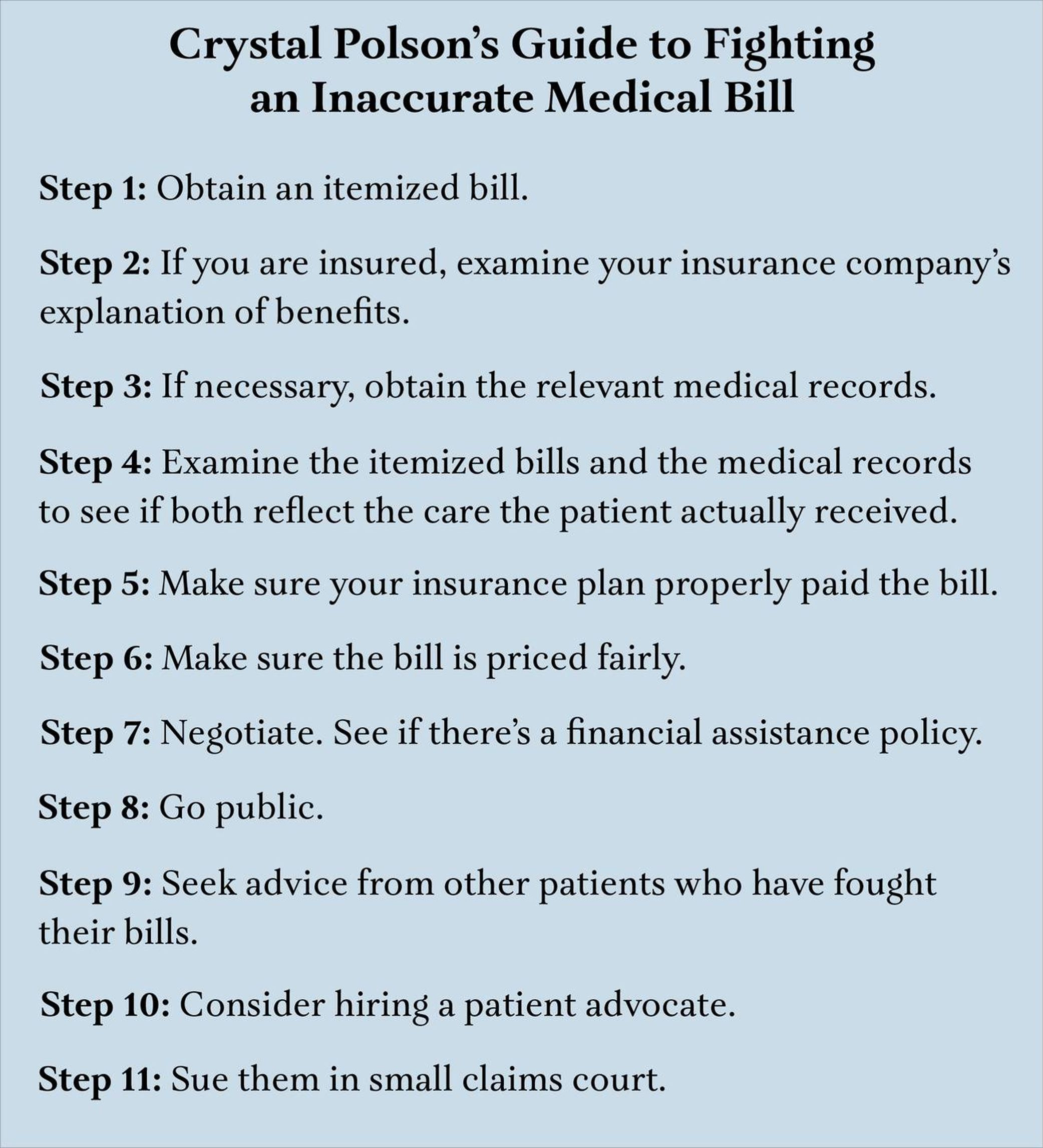

You write that Crystal Paulson, a nurse and patient advocate, recommends eleven steps consumers should take to fight back against incorrect bills [see below], with Step One being to request an itemized bill. Why do you get itemized receipts at the grocery store but it's not mandatory that hospitals send them out?

It should be required. I think it's a deliberate attempt to conceal costs. I think the more they can hide the itemized prices, the more they can get away with overcharging people.

We're in this situation we're in because our elected officials have allowed this to get worse and worse.

Baked into our market-based health care system is profit — for the hospitals, insurance companies and pharmaceutical firms. What can we do to change the equilibrium, so they put more emphasis on patients and less on profits?

We can do a lot about it. We need to use this new [Trump administration's] hospital price transparency rule requiring hospitals to post prices [online]. So far, compliance is spotty and the financial penalty for not complying is small. But it's a chance to reward the fairly priced hospitals and shun the overpriced ones.

You spent five years in the ministry earlier in your career. How did that inform your interest in health care?

I end up looking at the health care system through more of a moral lens, what's fair and what's not fair, what's ethical and what's unethical.

It's not fair to charge one patient more than another for the exact same service at the exact same hospital just because one patient has one insurance plan and another has another insurance plan.

It's not fair for hospitals and insurance companies to set their prices in secret and then just demand that the patient pay it when the patient could pay much less, in some cases, by paying cash.

They're fundamental inequities in the way our system is set up. And that's what I'm trying to help people understand, expose and then show them how to fight back and win.