Love 'em or Hate 'em, Pink Flamingos Live On

How a lawn ornament from the '50s became an icon with staying power

You might see them haunting a lawn near you: the Zombie Flamingo. They are the undead progeny of the first pair of plastic pink flamingos — created just shy of 60 years ago by the late Don Featherstone. Destined to become a pop culture icon, the birds rose to popularity alongside Elvis and suburbia — and managed to survive in spite of the hippie movement and just plain good taste.

“It’s been said there are more plastic flamingos in the United States than real ones,” says Bruce Zarozny, president of Cado Products in Fitchburg, Mass., which produces the celebrated Don Featherstone pink flamingo. “We ship thousands of them every year. [Don] used to say, ‘Tacky never goes out of style.’”

Flamingos — the real ones — became the rage with Floridian resort owners in the 1920s. The Flamingo hotel, which opened in 1921 in Miami Beach, associated the brilliant bird with opulence and glitz. Gangster Bugsy Siegel followed suit in 1946 with his Flamingo Hotel in Las Vegas (although some say it was named after his red-haired girlfriend Virginia Hill who was nicknamed “The Flamingo”).

After World War II, Americans began to move to suburbia, but some grew tired of the sameness of the neighborhoods and wanted to claim a little individuality. So they began to decorate their yards with statuary — cheaper and perhaps insolent imitations of the aristocrats’ carved garden sculptures.

Thinking Pink

At the time, pink was the “in” color — washing machines, stoves and refrigerators came in petal pink and other hues. Elvis Presley bought a pink Cadillac in 1956 after signing his first recording contract. So when young Featherstone, an art major working at a plastic factory, created the pink plastic flamingo design for Union Products in 1957, middle-class America immediately embraced it.

“You had to mark your house somehow,” Featherstone told Smithsonian magazine in 2012. “A woman could pick up a flamingo at the store and come home with a piece of tropical elegance under her arm to change her humdrum house.”

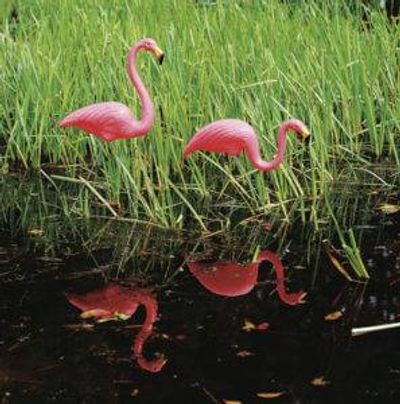

Featherstone’s flamingo pairs (with one bird grazing, and the other on sentry duty) became quirky totems for those thumbing their noses at the elite. For others, they were tacky and reprehensible. In the ’60s, plastic became a symbol of the establishment, so the hippie generation rejected the flamingo in favor of natural-looking fountains and rock gardens, explains Jennifer Price in her book, Flight Maps: Adventures with Nature in Modern America.

But by then, the bird had established a loyal fan base. When John Waters created his quirky 1972 film, Pink Flamingos, the lawn birds achieved a cult reputation. By the 1980s, they had crossed over into the shallow waters of glam, serving as themes at fundraising bashes and offering up their elegant heads as croquet mallets on the lawns of the wealthy, with a nod to the croquet game in Disney’s 1951 film, Alice in Wonderland.

A Prize for the Pink Flamingos Creator

Featherstone moved up the ranks at Union Products, eventually landing in the president’s chair. In 1996, he received the Ig Nobel Prize for Art by Improbable Research, which recognizes “achievements that make people laugh then think.”

The all-white Snomingo (now discontinued), a cousin of the original, was introduced the same year, followed by the taller Realmingo. Featherstone’s signature appeared engraved on the bottoms of the birds from 1987 until 2001, a year after his retirement from Union Products. The removal caused an uproar among Featherstone’s fans, and the journal Annals of Improbable Research teamed up with the Museum of Bad Art (MoBA) to boycott the unsigned birds, saying the company was removing the signature of an artist from his work. Union Products restored the signature.

Although many companies now produce similar styles of flamingos, lawn ornament purists will settle only for the Featherstone-signed classic and its cousins. A regal pair resides at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. And in 2011, Disney honored Featherstone by naming a character after him: the pink plastic flamingo in the movie Gnomeo and Juliet.

Flocking Together

Cado Products purchased the company in 2010, and continues the flamingo line, including the Realmingo, Caribbean Blue Flamingo and the newest member of the flock, the aforementioned Zombie Flamingo. Alternate colors are also custom-manufactured.

“Sometimes people buy dozens of flamingos and ‘flock’ peoples houses,” Zarozny says. “They use them as fundraisers — supporters pay to have them placed on someone’s lawn.” The “flockee” then will often pay to have them migrate to someone else’s home. Featherstone’s own Massachusetts home was a nesting ground to 57 plastic birds, celebrating the year of his flamingo’s “hatching.”

Featherstone died in 2015, but his creation lives on. “We are so proud to have the Don Featherstone flamingo in our line,” says Zarozny. “People like them because they are fun, and they have a huge following."