How to Protect Your Retirement Investments

The long stock market run-up means it's time to safeguard your money

What goes up must eventually come down, as every student of science and stock markets knows. This week’s upcoming 30 anniversary of Black Monday, the single worst day in Wall Street history, is a fitting occasion to consider whether you’re prepared for the time when gravity inevitably brings soaring stock prices back to earth.

No one anticipates a repeat of that fateful day in 1987 when the Dow fell 22.6 percent, the equivalent of a 5,000-point freefall at current levels. Nor are market pundits saying a bear market (when prices drop 20 percent or more) is imminent. Certainly the average investor isn't worried: In a new Wells Fargo survey, 65 percent of working Americans say the U.S. stock market is now a good place to invest for retirement, up from 45 percent a year earlier.

What Bull Markets Die Of

Still, there’s reason to be jittery — and not just because this month is also the 10 anniversary of the start of the financial-crisis downturn that cut stock values by more than half over 17 months. The current run-up, after all, is the second longest and strongest on record; an 8 ½-year climb that has more than quadrupled equity prices. Stocks are expensive by historical standards, too. And you never know what exogenous event could be a trigger for a scary market drop. (It’s an old Wall Street adage that bull markets die of fright, not old age.)

“Many people have become complacent because this bull market has gone on for so long,” says Christine Benz, director of personal finance at Morningstar. “But the risks are really quite high.”

That’s especially true for near- and early-retirees who have less time to ride out losses than younger people. So how can you protect yourself?

While the standard advice to “stay the course” no matter what the market does in the short-term still holds, imagine the course as a three-lane highway. If you’re close to, or already in, retirement, it’s time to start shifting to the right, where cautious driving prevails.

Fill the Buckets of Your Retirement Investments

Incidentally, even a mild stock-market loss or an extended period of below-average returns can inflict serious damage if they come early in your retirement.

The reason: If you need to sell investments to cover your living expenses, you’ll lock in those losses. And since you’ll have a smaller balance left in your portfolio, you’ll gain less when stock prices eventually recover. And solid growth in your investment portfolio is critical to ensuring your money will last your lifetime.

Here’s an example to show how an early-retirement stock decline can sting: Consider two hypothetical investors, Joe and Janet, who both start retirement with $1 million in savings, withdraw $62,000 a year from that stash to live on (adjusted annually for inflation) and earn an average of 7.56 percent annually over the next 30 years. Joe’s portfolio loses 10 percent in the first year before rebounding, while Jane earns the same 7.56 percent every year. According to financial planners Harold Evensky and Deena Katz, Janet will make it through retirement with nearly $100,000 to spare. But poor Joe will run out of money after 22 years — eight years shy of the goal.

How can you avoid Joe’s fate?

The Mental Shift

First, do a mental shift.

Think of your retirement savings as three buckets. The first bucket should hold enough cash and short-term investments to cover your living expenses for a year or two, when combined with your Social Security benefits, pension and other income. The second bucket, mentally earmarked for the middle years of retirement, holds bonds; the third bucket, with stocks, covers the last years.

If you’re within a few years of retirement or already retired, start filling up that spending bucket now, by selling a portion of your biggest-winning stocks and putting the proceeds in cash investments, like a money market fund and a short-term bond fund. Once you stop working, you’ll pull money for living expenses from this part of your portfolio and replenish, as needed, from the other two buckets.

There’s a psychological benefit to this strategy too: Knowing that near-term expenses are covered, says Benz, “helps keep people in their seats at market inflection points.”

Alternatively, says Wade Pfau, professor of retirement income at the American College and author of the new book, How Much Can I Spend In Retirement?, once you retire, you could use some of your savings to buy an immediate annuity from an insurance or investment company. This financial product provides a guaranteed monthly income for life. (You can see how much money you’d receive monthly based on your age, gender and the amount you’re investing here.)

The downside of an immediate annuity: You typically give up access to your money in exchange for the lifetime income guarantee. And if you die soon after buying it, you will have shelled out a relatively large amount for a small number of payments. (You can buy an immediate annuity to be left to your heirs, but it will pay less income.)

The upside: Studies from Towers Watson and others show that retirees who annuitize tend to be happier and feel they have a higher standard of living than those who rely on savings alone.

Take a Goldilocks Approach

Another way to protect against big losses but keep your savings growing to last 30 years or more is by taking a Goldilocks approach to investing. This means holding a portfolio mix that’s not too hot (heavy on stocks) and not too cold (heavy on bonds), but just right for you.

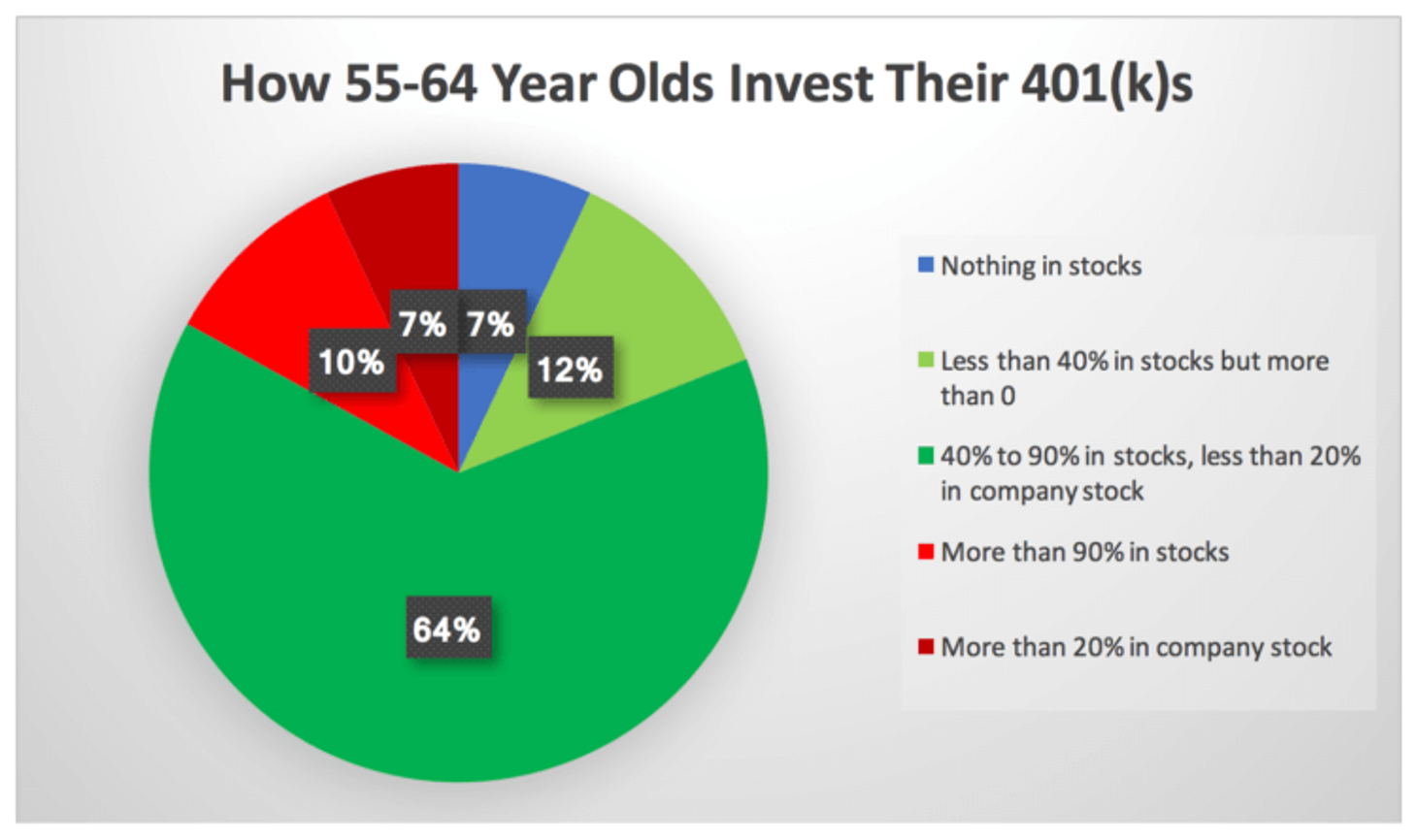

Yet many pre-retirees and current retirees have overloaded on one asset or the other. According to Vanguard, 17 percent of investors aged 55 to 64 have more than 90 percent of their portfolio in stocks or more than 20 percent in their own company’s shares. And one in five swing too far the other way, keeping less than 40 percent of their overall saving in equities, including 7 percent who own no stock at all.

At a minimum, if you haven’t adjusted the mix in your retirement account lately, rebalance now. The big stock market advance we’ve seen since 2009 means your investment weights are probably out of whack.

An account that was 70 percent in stocks/30 percent in bonds at the outset of the bull market would likely have about 88 percent in equities now. So, shift money out of your biggest winners and into bonds to lock in some gains and find the right balance.

Also, revisit those asset allocation targets to see if they still make sense.

For people who are near, or have recently begun, retirement, 30 to 60 percent in stocks is usually a reasonable range, Pfau says, adding the low end of that spectrum should be viewed as the absolute minimum. “The more aggressive you can be the better, as long as you won’t get scared and sell stocks after they drop, which is the worst possible reaction,” says Pfau.

One easy way to pour yourself an optimal portfolio blend: Move your savings to a target-date fund. It assembles a mix of stocks, bonds and other assets based on when you want to retire, and then gradually shifts to more conservative investments as the goal gets closer.

Target date funds are a handy tool to help retirement savers of all ages ride out market storms, Benz says.

Be Flexible About Investment Withdrawals in Retirement

You have another lever to pull if a market slide threatens your portfolio early in retirement. You can fiddle with how you’ll tap those assets when you need to start withdrawing money from your investment portfolio.

To avoid outliving your money, the traditional advice financial planners offer is: withdraw 4 percent from your savings in Year One of retirement and increase that amount annually to keep up with inflation. Instead of that, be flexible. Drop your annual withdrawal rate to 3 percent when the market is down or simply forgo the annual inflation adjustment until stocks recover.

Giving up your annual “raise” will feel like less of a hardship than an outright cut in spending. You probably won’t have to deprive yourself for long. The average bear market lasts about 14 months.

Just as you can’t count on the good times lasting forever, it’s comforting to remember the inevitable bad turns won’t either.