Providing Spiritual Care After a Disaster

How a semi-retired pastor offers presence and compassion to those in need

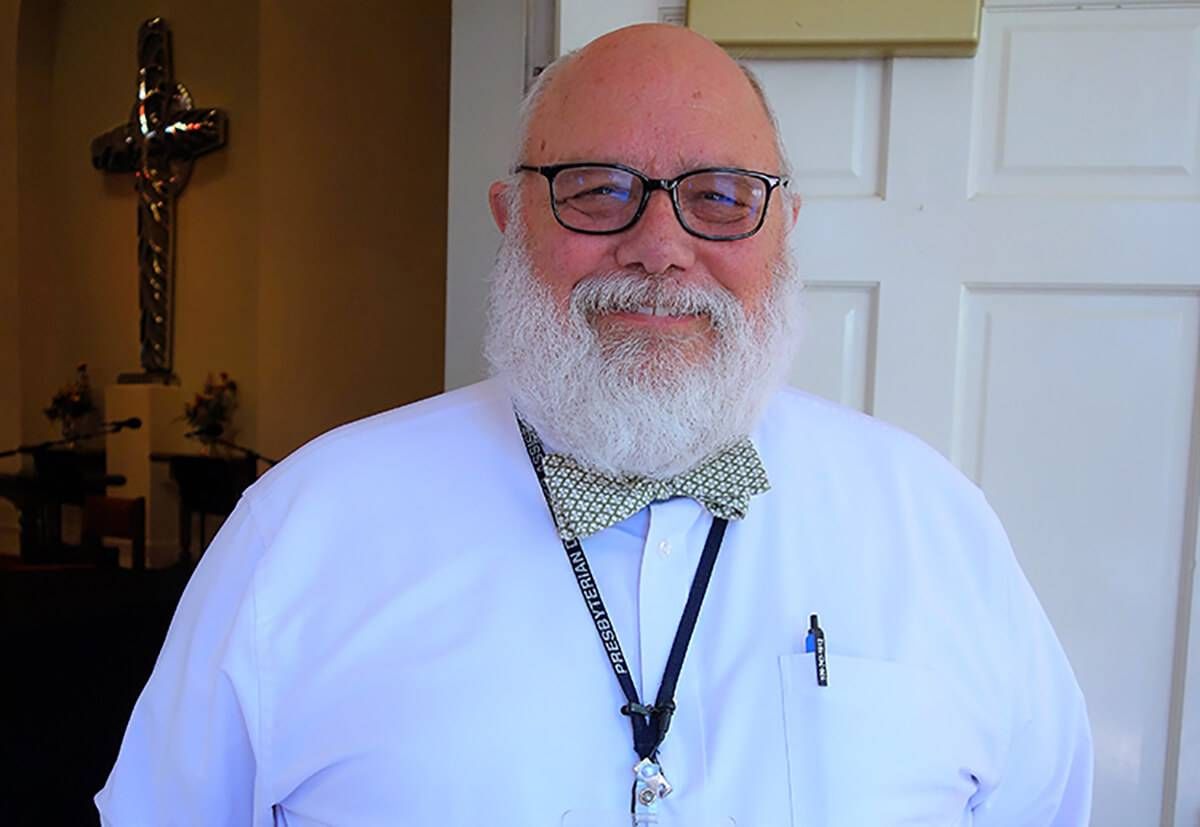

On the evening of July 21, 2012, the night after a mass shooting at an Aurora, Colo., movie theater, a crowd gathered on a nearby hillside to remember the victims. Among those in attendance was Rev. John Cheek, an associate pastor at a Presbyterian church in Tucson, 900 miles to the south.

Representing Presbyterian Disaster Assistance (PDA), an agency of the Presbyterian Church U.S.A., Cheek had deployed to Aurora that morning, along with a fellow PDA volunteer from California; two other volunteers from Massachusetts and Florida would arrive the next day. All four were flying in on one-way tickets, prepared to stay as long as necessary to provide spiritual care to those affected by the tragedy — especially church leaders, chaplains and other caregivers.

“On Sunday, each of us went to a different church, so there was a PDA presence at each of the PC (USA) churches in Aurora,” Cheek said. “We had the chance to speak about what PDA does and why we were there, to make ourselves available after worship for anybody that wanted to talk to us.”

PDA, the Presbyterian Church U.S.A.'s emergency and refugee program, provides emotional and spiritual care, as well as long-term recovery assistance, to communities affected by natural and man-made disaster. Each year, the 100 volunteers on PDA’s national response team deploy about 60 times. In 2017, volunteers spent 2,122 days in the field supporting 70 of the denomination’s 170 presbyteries (regional bodies).

Responding to Immediate Needs

As Cheek and his colleagues explained that morning in Aurora, PDA volunteers don’t come to town to preach or otherwise usurp the role of local pastors and caregivers. “This congregation needs to hear their pastor, but he or she may need some help from us if they’ve not been through this type of trauma before,” Cheek said. “There may be an immediate need for me to sit and hold a woman’s hand and let her weep. Of course, I’m going to do that, but in the longer run, her pastor is not going to be me.”

In Aurora, none of the PC (USA) congregations had primary victims, although all four had secondary victims (a former co-worker, a neighbor’s son, etc.). So Cheek and his colleagues spent much of their time at local hospitals.

“One of the most important things we had a chance to do was to work with hospital chaplains, who were tremendously tasked with the work of caring for all of these victims coming into the hospitals,” said Cheek.

Cheek sees his work as a ministry of presence, not of problem-solving. “Many of us want to fix things,” he said. “There’s not much fixing that happens in disaster, but there is a lot of standing together, sitting together and holding hands. That’s the vital work in that context.”

Inspired by Volunteers

PDA volunteers had sat with Cheek a year earlier, when a gunman shot U.S. Rep. Gabrielle Giffords and 18 other people about two miles from Cheek’s home. Among the six people killed that day were U.S. District Judge John Role, a longtime friend, and Phyllis Schneck, a member of Cheek’s congregation; two other congregation members were wounded.

PDA quickly deployed three volunteers, two of whom ended up staying for 11 days. “David Holyan, who’s a pastor in Kirkwood, Mo., was the first one to see me,” Cheek recalled. “He walked up to me, and he flung his arms around me. He said, ‘I’m so sorry.’”

Seeing volunteers like Holyan at work inspired Cheek to get involved with PDA. He also sensed that his unique background might come in handy: At the time, he’d only been a pastor for about six years, but before that, he’d been a Tucson police officer for more than two decades.

“I have found the 24 years I spent as a police officer have been beneficial to me in terms of being able to keep my head in the game when there is some kind of significant disaster,” Cheek said. Besides being able to maintain composure in traumatic situations, he can translate police jargon and interpret police procedures for his teammates and the other second responders he works with.

A Career Change

Across his law enforcement career, people often told Cheek he’d missed his calling and should have been a pastor. He agreed, even as he pursued his only professional goal: becoming a hostage negotiator, a position he held for five years. “I was in the best possible situation a person could be in, and I began to feel unsettled and feel like I wasn’t doing what I was supposed to be doing,” he said.

After much prayer and discernment, Cheek enrolled in Fuller Theological Seminary’s Tucson extension program in 1996, taking his first class in uniform during a work break. He was ordained nearly nine years later and served Northminster Presbyterian Church for nearly 12 years.

Cheek retired from that church last year, but still serves a church in Silver City, N.M., 200 miles from Tucson, on a part-time basis. “I’m there typically two Sundays and the week in between,” he said.

He’s also frequently on the road with PDA. Just a week after Hurricane Irma hit Florida in September 2017, he traveled to Jacksonville, Orlando, Okeechobee and Tampa to help pastors and community leaders access resources they needed. He returned to Tampa a month or so later to lead resilience training for pastors, something he has done more recently in Austin with Texas pastors affected by Hurricane Harvey.

With two careers mostly behind him, Cheek might be tempted to coast through retirement, but that’s not going to happen. “The 24 years I was in police work, I didn’t realize it, but it was ministry internship,” he said. “God has prepared me to be present with people in disaster; it would be unthinkable for me not to be present to people since God has prepared me for it.”

And so the next time the phone rings, Cheek will grab his suitcase, book a one-way ticket and travel into tragedy. “We cannot fix it, but we can be present,” he said. “And being present is a really big thing.”