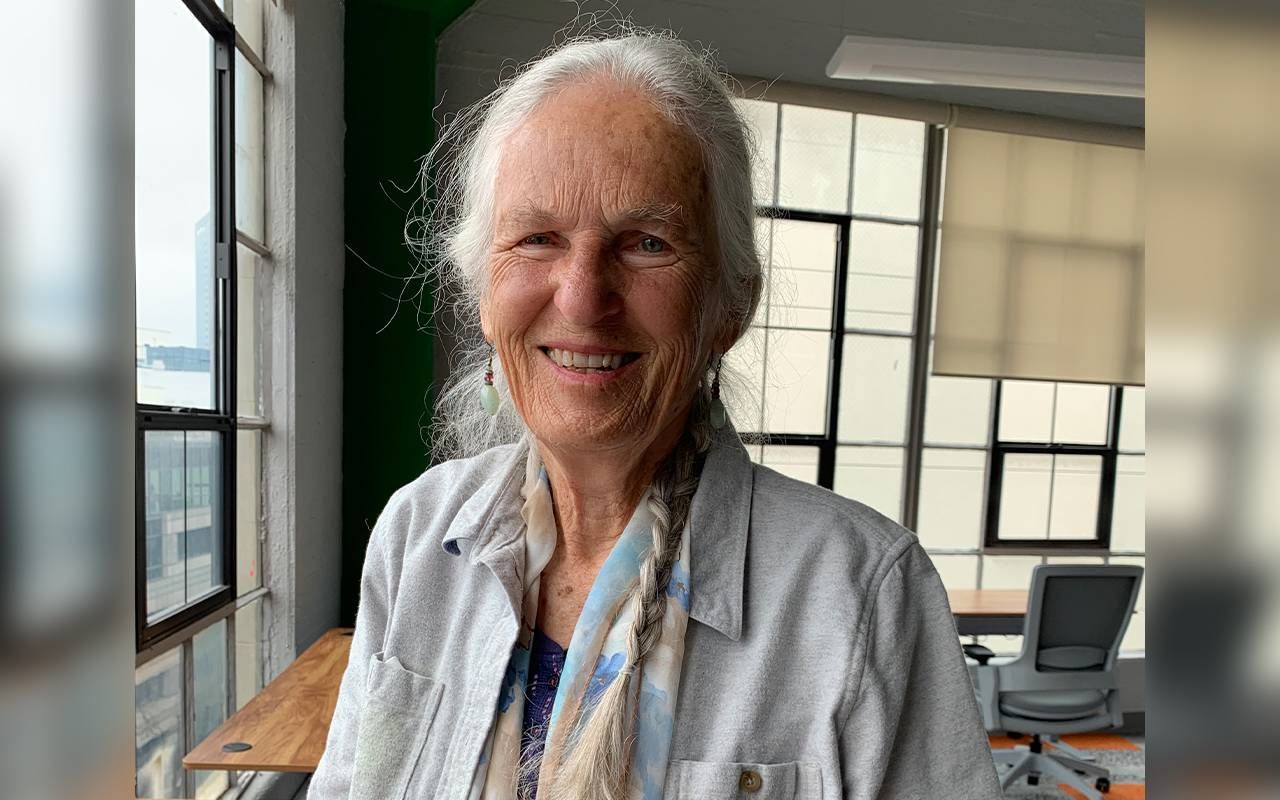

Rasa's Story

An 88-year-old Lithuanian American recalls her harrowing journey escaping the Russians in the 1940s

The first time the Russians marched into Lithuania, Rasa Gustaitis was six years old. She was with her grandmother in the backyard when she heard a neighbor call out the news. Gustaitis recalled the fear on her grandmother's face as she whispered, "Bozhe Moi," ("My God"). It was June 15, 1940.

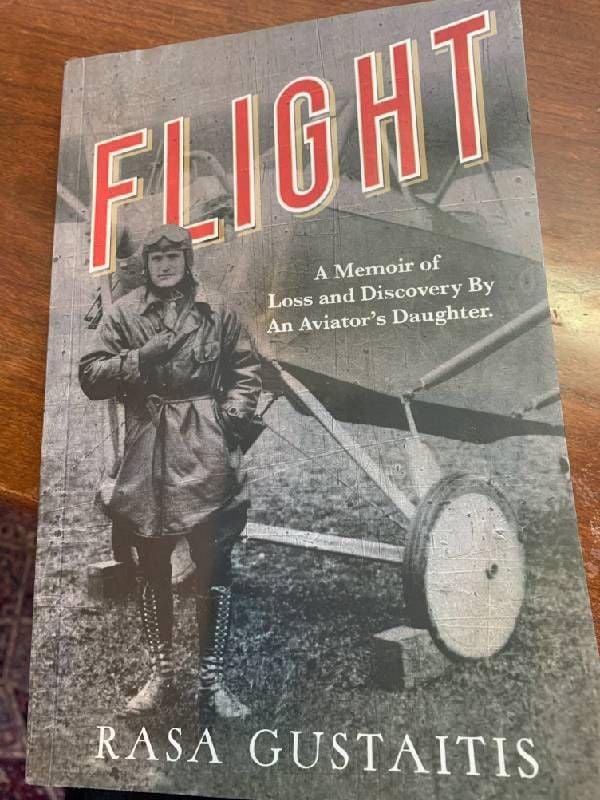

Gustaitis's father, General Antanas Gustaitis, was the head of the Lithuanian Air Force at the time and well-known for his contributions to aero-engineering. Realizing that the family was in danger, he convinced Gustaitis's mother to make plans to escape without him. In his own bid to cross the border, General Gustaitis was captured and taken away by the Russians on March 4, 1941.

Claiming to be of German descent, Gustaitis's mother and grandmother gathered the three children, one an infant, and boarded a train to Poland, then under Nazi occupation.

Gustaitis received evidence of her father being captured and taken to Butyrka prison in Moscow, relentlessly interrogated and later executed in October, 1941.

When she was in her early eighties, Gustaitis reconstructed her past in a memoir she worked on for eight years, aptly named "Flight." The memoir dredges up details of the family's harrowing journey out of Russia-occupied Lithuania — twice — and their resettlement in New York, Gustaitis's assimilation into American life, and then later the reconnection to her father's personal and aeronautical history in Lithuania.

Now in her late eighties, Gustaitis, who lives in the San Francisco area, is tall and regal-looking with long flowing hair, a beautifully expressive face and a soft and serene manner of talking. "The history slips down easily," Gustaitis told me as we sat in her living room and talked about Russia's incursion into Ukraine and its relevance to her own troubled past. "Putin has said he wants to restore the Soviet Union boundaries. That was also Stalin's thing."

In July 1940, Stalin annexed Lithuania, the southernmost Baltic state, and declared it part of the Soviet Socialist Republic. Thousands of Lithuanians were deported to the Gulag in Siberia and a number of high-ranking Lithuanians were captured and killed. Gustaitis received evidence of her father being captured and taken to Butyrka prison in Moscow, relentlessly interrogated and later executed in October, 1941. These documents compiled in a Moscow prison are now part of Lithuania's Special Archive in Vilnius.

Out of Lithuania, Twice

In the memoir, Gustaitis writes lyrically, and with journalistic precision captures the essence of what was lost and found in the aftermath of war.

The first time the family of five escaped from Lithuania, it was in the middle of the night. They boarded a train that stopped at small stations where red flags with a hammer and sickle flew from poles. When they reached German-occupied Lodz in Poland, the Nazis singled out Gustaitis's older sister, Jurate, who was a shade darker-skinned than the others, measured the circumference of her head and photographed her before letting her rejoin the family.

Gustaitis and her family sheltered first at a school and then at a summer camp for displaced persons.

"Unfathomable evil was ravaging Eastern Europe and surely an awareness of its presence crept into every child."

Soon after, on June 22, 1941, the Germans launched Operation Barbarossa, invading the Soviet Union and driving the Russians out of Lithuania. Believing that it was safe for them, and in the hope of reuniting with her husband, Gustaitis's mother took the family back to Lithuania.

Gustaitis's memories of that period are trauma-filled. "Unfathomable evil was ravaging Eastern Europe and surely an awareness of its presence crept into every child," she wrote. It is estimated that over 200,000 Jews died at the hands of the Nazis in Lithuania, the highest victim rates in Europe.

Gustaitis recalled watching through the window of a school bus a man with a yellow six-pointed star patch on his back being chased by German soldiers. Gustaitis wrote of Jurate witnessing German soldiers shoot at a group of naked people standing in front of a ditch, "who then fell, one by one, into the ditch."

The family coped the best way they could. While Jurate found solace in playing the piano, Gustaitis discovered religion, coming to the realization that the Catholic Church was a safe haven, where "no evil existed."

The second time out of Lithuania was in 1944 when Stalin mounted a counteroffensive against the Germans. The family once again took flight. On this second train ride out of Lithuania, Gustaitis was ten years old. She wrote of how the rattling of the train sounded out "goodbye my dearest Lietuva," and as she watched the familiar landscape recede into the past, she felt some bread crumbs lodged between her thighs, and this discomfort felt "somehow right."

Gustaitis and her family disembarked in Vienna before heading to Graz in Austria. A Ukrainian family with two children lived next door to their apartment. Gustaitis remembers playing with the Ukrainian girl and it was a day of terror and grief when she heard one day that the Ukrainian girl and her brother had been killed by a bomb. "She comes to mind a lot now," Gustaitis said.

Arriving in the United States

After Hitler was defeated, Gustaitis's family secured passage to America on the SS Ernie Pyle, a Merchant Marine vessel, with the sponsorship of an aunt in Brooklyn, New York.

On arriving in Brooklyn, two things struck Gustaitis as unusual. First, there were no broken windows — signifying no bombings — and there was trash on the streets. This was unusual even in the heavily bombed parts of Europe, according to Gustaitis.

Gustaitis enrolled in public school and found that first year in Brooklyn tough. In a conversation we had on her sun-filled patio overlooking a flowering garden, she told me that she had found it hard to relate to the other kids in the school.

"There was no other displaced person there and I was pretty weird to the kids. For one thing it seemed to me that my classmates were much older than me because they were dressed like adults instead of like kids. I still had pigtails and a short dress and they wore heels and nylons," she said. But after a couple of years in Brooklyn, she received a scholarship to Dana Hall, a boarding school in Wellesley, Massachusetts.

Gustaitis's life in America proceeded steadily forward after that. She enrolled at Oberlin College for undergraduate studies and then on to Columbia University for a graduate degree in journalism. She started her career at the Washington Post, before moving on to the New York Herald Tribune and then Pacific News Service in San Francisco, while authoring a number of non-fiction books.

"In many ways, I think I've been very privileged. Yes, we left with a couple of suitcases and my grandmother's down comforter, but I was able to come here and had this miraculous good luck," Gustaitis remarked.

Memory and Memoir

"Writing a memoir gives a form and a shape to experience," Gustaitis said. Though, "there were lots of things I didn't remember at all," she admitted during a book reading event. There were many instances when she questioned her own recall, she said.

She related one such incident with vivid detail in her memoir. When she was walking home from the park one day, Gustaitis described seeing a boy blow himself up with a grenade near Vytautas, the Great War Museum. She heard an explosion, and when she turned to look, she saw a boy's knees, "pulled up the way I would pull up my knees while lying in a meadow and looking up at the sky." When Gustaitis checked with Jurate about the incident, Jurate said, "I'm sure that didn't happen because I would have known about it."

"Yes, we left with a couple of suitcases and my grandmother's down comforter, but I was able to come here and had this miraculous good luck."

Gustaitis nevertheless included the incident in her memoir. "If it's not correct, it's nevertheless what I remembered," she explained.

Looking pensive, Gustaitis said that writing "Flight" wasn't always easy. It required a lot of reflection and talking to the people who were involved at that time. "One can check historical facts, but it's tough to fact-check memories," she said.

On one of her trips back to Lithuania, Gustaitis visited the museum where her father's first plane was displayed. All the Lithuanian aircraft had been destroyed by the Russians, but this one plane had been taken apart and hidden in the basement of a musician and later reconstructed. The director of the State Archive showed Gustaitis a film of the test flight of that plane.

"Making a reconnection is to awaken a forgotten sorrow," she said, as she described these details. In a 2014 trip to Lithuania, she read the preserved Russian dossier "Byla 1066 A. Gustaitis" on her father's final days.

What Remains and What's Lost

From food to language there are similarities among people from the Baltic states. "Everybody eats borscht," remarked Gustaitis. Most families develop their own recipe for it. "My family's version is more Ukrainian borscht, more consolidated. My daughter and stepdaughter worked on our family borscht recipe and we are convinced it's the best," she said with a smile.

According to Gustaitis, the Ukrainians are not that different from Lithuanians and others from that region, nor from Russians. "You meet a Ukrainian here and often they will say, 'I have many friends who are Russians.' We spoke both languages. It's crazy, it's like brothers shooting each other."

Discussing the state of the world today, Gustaitis sees the parallels from her own days as a refugee. Displacement and resettling are facts of life now. People are escaping all manner of tragedies, from wars to gangs to discrimination.

"I mean, it's a myth that everybody comes here to get a better life. They come here to live," she said.