Reflections on My Days Working With the 'Founding Mothers' of NPR

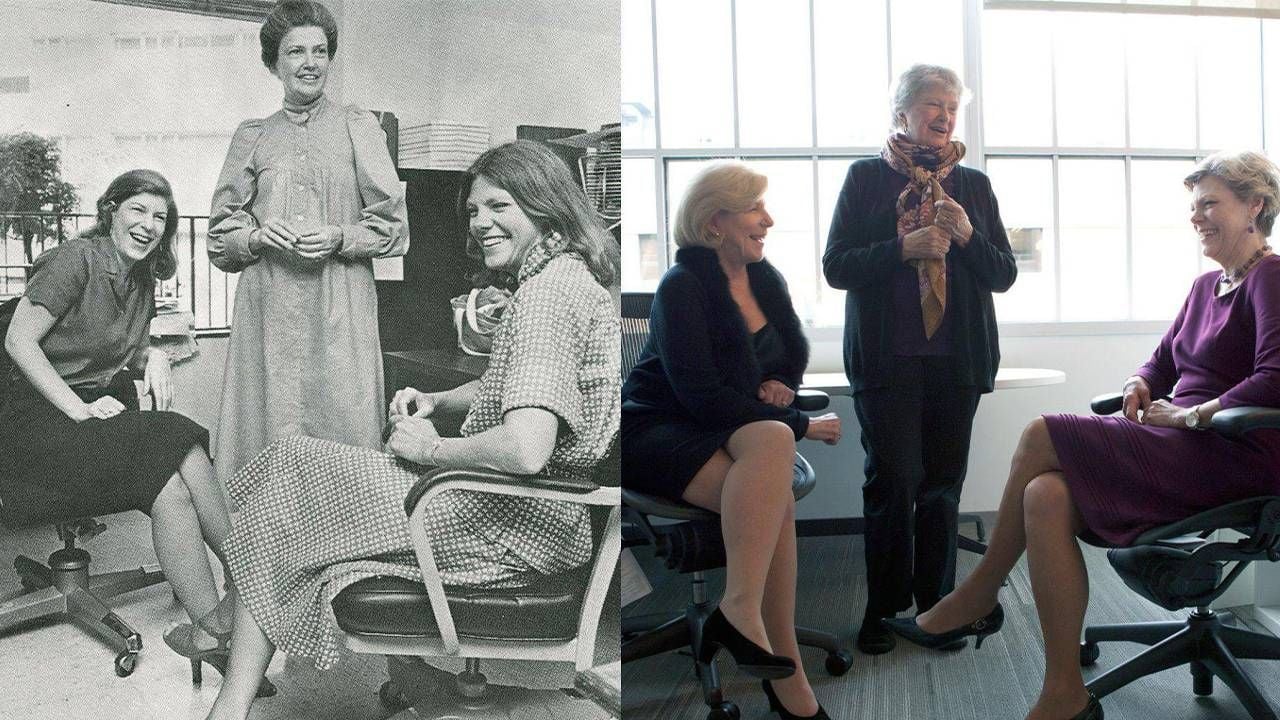

Looking back and catching up with three of them: Susan Stamberg, Linda Wertheimer and Nina Totenberg

Editor’s note: With National Public Radio (NPR) approaching its 50th anniversary and the release of the book "susan, linda, nina & cokie" about NPR broadcasters Susan Stamberg, Linda Wertheimer, Nina Totenberg and Cokie Roberts, Next Avenue has published an article by Richard Harris, "The Founding Mothers of NPR." Harris worked at NPR for years with those groundbreaking women and offers a personal account here.

Sometime in the early 1970s, word spread around my college radio station outside Chicago that a new public radio network had recently been launched in Washington, D.C. National Public Radio was apparently desperate for content.

Ted Koppel paid NPR the biggest compliment when he told me that he wanted "Nightline" to be more like "All Things Considered."

So, this undergrad put some stories together including one during my senior year about the controversial artificial sweetener cyclamate — and was a bit surprised to be sent to WBEZ, the Chicago public radio station, to feed it over a phone line to the network for NPR's afternoon newsmagazine "All Things Considered." And then, to hear it on the air on a show I admired.

As I was preparing to graduate from Northwestern, someone at NPR tipped me off to a job at WOI Radio, the public radio station in Ames, Iowa that was reported to be one of the stronger stations in the system.

One day, doing a statewide newscast there, I learned an important lesson. If you're from Boston and unfamiliar with different types of cattle, it's best to ask a local how to pronounce 'heifer' before you go on the air and make a fool of yourself. (For the record, it's HEFF-er, not HIGH-fer). The phone lines lit up with listeners asking: "Who is that city slicker doing the news?"

The NPR Coverage That Made History

Before I could do any more damage, Senate Majority Leader Robert Byrd gave NPR permission to air gavel-to-gavel debate from the Senate chamber. This historic decision prompted a call from NPR headquarters in Washington, D.C., asking if I would be among six member-station producers to temporarily relocate to Washington to help produce "All Things Considered" while the regular staff was shifted to the historic broadcasts.

It all became official on February 8, 1978 when NPR's Linda Wertheimer spoke these words: "Today is the first time in our 200-year history that the debates in the Senate will be heard far beyond the chamber and its visitor's gallery." So began nine weeks of debate on the Panama Canal Treaty, broadcast live on NPR stations.

Wertheimer recently told me it was a highlight of her distinguished career: "The thing the Democrats were so panicked about was they didn't think they could explain giving away the Canal. It was part of our mythology, and to give it away was a bad idea."

The morning after I arrived in Washington, I came down for breakfast at the hotel where NPR put up its temporary producers and noticed Sen. George McGovern, the 1972 Democratic presidential nominee, walk in. That was the moment I knew I wasn't in Iowa anymore.

Around the corner at NPR, I felt like a beginning swimmer getting thrown in the deep end of the pool. I would listen to Susan Stamberg or Bob Edwards record an interview for "All Things Considered," then under deadline pressure, I would take the large metal reel of recording tape and edit it on a splicing block with a razor blade to fit whatever hole was needed in the show. I quickly learned the art of fishing missing syllables from the trash can and splicing them onto the tape that would soon air on the broadcast. I had to pinch myself occasionally that they were paying me — though not much — to do work I so enjoyed.

Reuniting With the 'All Things Considered' Crew

When the Canal debate ended, it was as though my carriage had turned back into a pumpkin. I returned to Iowa. But not for long. A few months later, an opportunity at NPR allowed me to reunite with the "All Things Considered" crew and this time, as a full-timer.

Cokie Roberts, the fourth of the NPR Founding Mothers had just joined the network. And were it not for the 1983 NPR funding crisis that coincided with the impending birth of our first child, who knows how many decades I might have stayed at the network.

In many ways, I have NPR to thank for getting hired at ABC's "Nightline." Host Ted Koppel paid NPR the biggest compliment when he told me that he wanted "Nightline" to be more like "All Things Considered." And it was at "Nightline"where I got to work once more with two of NPR's Founding Mothers: Cokie Roberts, who joined ABC News while maintaining at least a weekly presence on NPR and who would substitute for Koppel on "Nightline," and on occasion, Nina Totenberg, who provided legal analysis.

No evening was more memorable for me than the night Totenberg sparred with Republican Sen. Alan Simpson, debating Anita Hill's allegations against Supreme Court nominee Clarence Thomas, a story Totenberg broke when she interviewed Hill.

As contentious as their "Nightline" appearance was, it was what I witnessed after the broadcast on the sidewalk in front of the ABC Washington bureau that left me slack-jawed. Totenberg asked me to escort her out of the bureau to her waiting car. As she got in, Simpson held the door open, called Totenberg an unethical journalist and wouldn't let the car go. Then Totenberg got out of the car, called Simpson "an expletive bully," then got back in and told the driver, "Let's go!" And as she rounded the corner, Totenberg recalls, the driver looked at her and said, "Lady, you need a gun."

Eventually, Totenberg and Simpson became friends, and she took him to the annual Radio-TV Correspondents dinner. Washington doesn't work well if reporter and source hold a lasting grudge.

Why 'The Founding Mothers' of NPR Have a Hold on Me

I've never been able to put into words why more than 40 years later, NPR and its Founding Mothers — Susan Stamberg, Linda Wertheimer, Nina Totenberg and Cokie Roberts — still have a hold on me.

I first met all of them in 1978. They taught me that tough journalism doesn't need to be accompanied by a gruff demeanor.

What I'll remember most about Cokie is that no matter the deadline and stress we were working under, she made a point of always asking, "How were Kit and the girls?"

Perhaps I should quote an NPR listener from Iowa City, who described Susan Stamberg in the Press-Citizen this way: "You don't deliver the news. You deliver humanity."

That humanity was on display when my wife Kit and I had dinner with Susan a few years ago and she took me aside to let me know that NPR was preparing an obituary for our mutual friend, Cokie Roberts, who would leave us a few days later. Hearing this awful news from Susan was a shock, but it was also a gift coming from her, so I could be prepared and wouldn't have to hear it first on the news.

NPR's four Founding Mothers had always supported each other in time of need, so it was no surprise that when we walked into St. Matthew's Cathedral for Cokie's funeral mass, there were Susan, Linda and Nina honoring the fourth, handing out programs and taking people to their pew.

What I'll remember most about Cokie Roberts is that no matter the deadline and stress we were working under, she made a point of always asking, "How were Kit and the girls?" (she updated this to "How were Kit and the young ladies?" as they grew up).

Steve Roberts eulogized his wife by telling those in the Cathedral and those watching on C-SPAN that in her last days of life, Cokie became friendly with one of her nurses and insisted that Steve rummage through her recipe box at home to find a recipe for crawfish cornbread. The author of that recipe, recalled Steve, was Big Lou, serving a life sentence at Louisiana's Angola Prison. But he was Cokie's friend too.

It seemed everyone was.