How Religious Belief Can Affect Health

One scientist used brain scans of rabbis to inform his research

Adhering to a well-balanced diet and incorporating exercise into your routine are two well-known ways to improve health. What about religious involvement? Can that also have a positive effect on health and well-being?

There’s a growing field of study that seeks to link the physiological effects of religious and spiritual practices on the body: neurotheology.

Dr. Andrew Newberg, a neuroscientist and pioneer in the field, defines neurotheology as exploring the link between the brain and our religious and spiritual selves. Newberg is director of research at the Marcus Institute of Integrative Health and professor of emergency medicine and radiology at Thomas Jefferson University and Hospital in Philadelphia. He is also the author of 10 books, including How God Changes Your Brain and Neurotheology: How Science Can Enlighten Us About Spirituality.

The History of Neurotheology

“The first place where I believe neurotheology appears in an academic setting was a 1984 article by James Ashbrook, Neurotheology: The Working Brain and the Work of Theology in the journal, Zygon,” Newberg said. “But in some ways, neurotheology is thousands of years old, as with the Hindu and Buddhist traditions and how they tie the spiritual to the mind.

A number of studies point to an association between religious involvement and decreased morbidity and mortality.

“Even in western religions such as Christianity and Judaism, there is a tie between the brain and how we function on a religious and spiritual level,” Newberg continues. “An example I like to give is the Ten Commandments: The Bible says that these are things we can do (Deuteronomy 30:11-14). But there’s the recognition that we are able to do those things by using our minds.”

The Relationship Between the Brain and Religion

As a medical student in internal medicine and nuclear medicine, Newberg spent a year in a lab focused on brain imaging and nuclear imaging. He worked with psychiatrist Dr. Eugene d’Aguili, a leader in neurological research of religion who was studying religious experiences.

“We started to talk about the relationship between the brain and religion, and a light bulb went off,” Newberg said. “I can do brain scans of people praying and meditating to try to understand what’s going on within the brain during those experiences.”

Newberg has employed various types of brain imaging technology in his research, including positron emission tomography (PET) scans, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and single proton emission computed tomography (SPECT).

“SPECT works very well, as it allows us to measure blood flow. And the more blood flow the brain gets, the more active it is,” Newberg said.

“We’ve studied many different practices — including Buddhist monk meditators, Franciscan nuns in prayer and people speaking in tongues — to capture a snapshot of the brain during those practices,” he continues. “By understanding how the brain works during religious experiences, we can begin to understand how religion affects psychological and physical health.”

According to Newberg, a number of studies point to an association between religious involvement and decreased morbidity and mortality.

Prayer and meditation increase frontal lobe activity and have been shown to increase dopamine, a chemical that allows the transmission of signals between cells. Prayer and meditation also have been shown to lower heart rate and blood pressure, which can reduce heart disease and improve life span.

“Those are the direct effects of religion, those that directly have an impact on the brain and body,” Newberg says. “There are indirect effects as well, such as religion providing a strong social network, which may help people cope better with various issues in life — health issues in particular — as well as reduce stress and improve mood, which makes our immune and hormone systems work better.”

The Rabbi’s Brain

Newberg’s religious background is Jewish, having been born into a reformed Jewish household. “While I am not overly religious, I certainly recognize the importance of that connection in my life to how I am and how I think,” he says.

A research project exploring how Jewish religious thought and experience may intersect with neurotheology led to Newberg’s collaboration with Rabbi David Halpern, a resident in the department of psychiatry and human behavior at Thomas Jefferson University. Together, they wrote the 2018 book, The Rabbi’s Brain.

“I realized that one of the next steps of neurotheology is to look at the context of each of the religions’ traditions, to delve into both the scientific perspective and the religious perspective,” Newberg says.

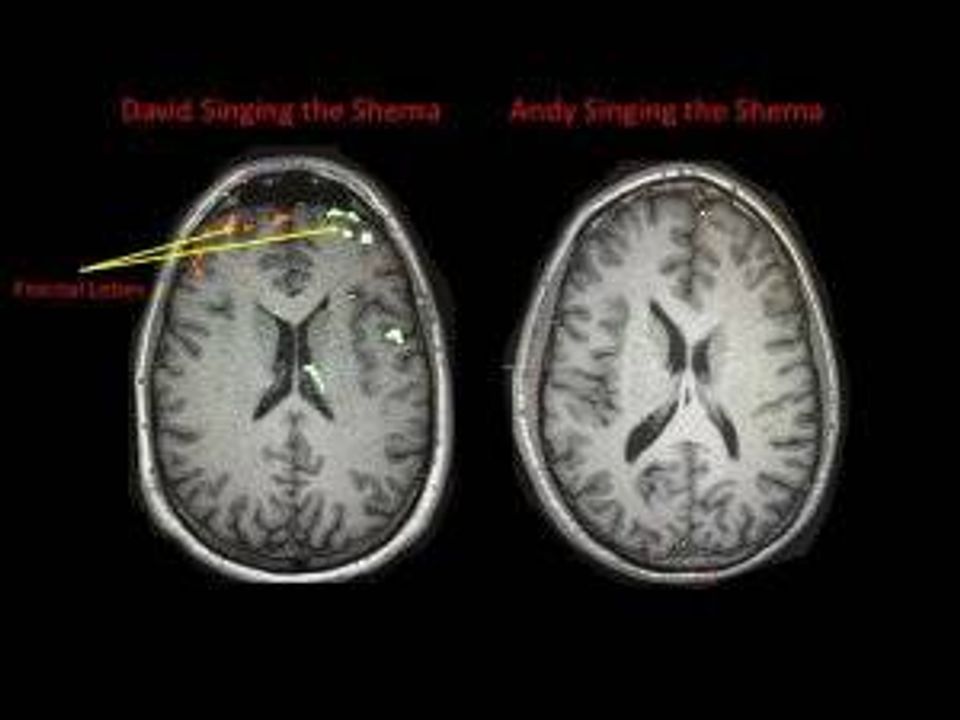

During their research, Halpern had his brain scanned while performing the “Shema,” one of the most fundamental prayers in Judaism. His brain also was scanned while singing a non-religious, well-known song.

“The results were unique, with one side of my brain activating, while the other side was deactivating,” Halpern says.

The area of increased activation was the right frontal lobe, and the decreased activation was in the left frontal lobe.

“This suggests that he had more intense focus on the prayer, but also had a sense of letting go or being taken over by the prayer process,” Newberg says.

Newberg's brain also was scanned while he did the same activities. “My brain did not do anything significant between singing the ‘Shema’ and singing a standard song,” he says. “So, for my brain, singing the ‘Shema’ is no different than singing some other song. David's brain had a completely different response, because the Shema is much more meaningful to his beliefs.”

In addition to brain scans, Newberg and Halpern’s research included a formal survey of 160 rabbis of various backgrounds and denominations.

"Just because we see the emotional centers become active on a brain scan does not mean we know what emotions the person is feeling,” Halpern says. “We asked questions like if the rabbis always wanted to be a rabbi, if they felt called by a role model or an experience, and, most importantly, what they thought about God and how emotions, thoughts and experiences contributed to their religious and spiritual beliefs.”

The Future of Neurotheology

Newberg believes that there’s a growing acceptance of neurotheology, and that recognizing people have a psychological, emotional, religious and spiritual component, versus just biological, plays an important role in the health care setting.

“I believe it’s important to keep science rigorous and religion religious,” Newberg says. “That means utilizing the best methodologies to advance science — possibly developing new techniques and approaches — while paying attention to, and understanding, what’s happening when people enter into prayer, liturgy and ritual through religious experiences.”