Remembering My Big Brother on Veterans Day

I’m saddened by his suffering and his death as a homeless man, and I hope for change

A friend who recently traveled to Washington D.C. told me she connected on the street with a homeless veteran. She provided him a meal and he asked her if she would come and see him the next day. She did and literally gave him some of the clothes off her back.

I thanked her, not just for being compassionate to a fellow human being, but to a person who is likely someone's son, brother, uncle. She said something that will stick with me: "I think he really just wanted to be seen."

The story made me think again of all the veterans recently coming home from America's longest war in Afghanistan, but also made me think of my brother, Steve.

I was 11 years younger and only have a few memories of the younger Steve.

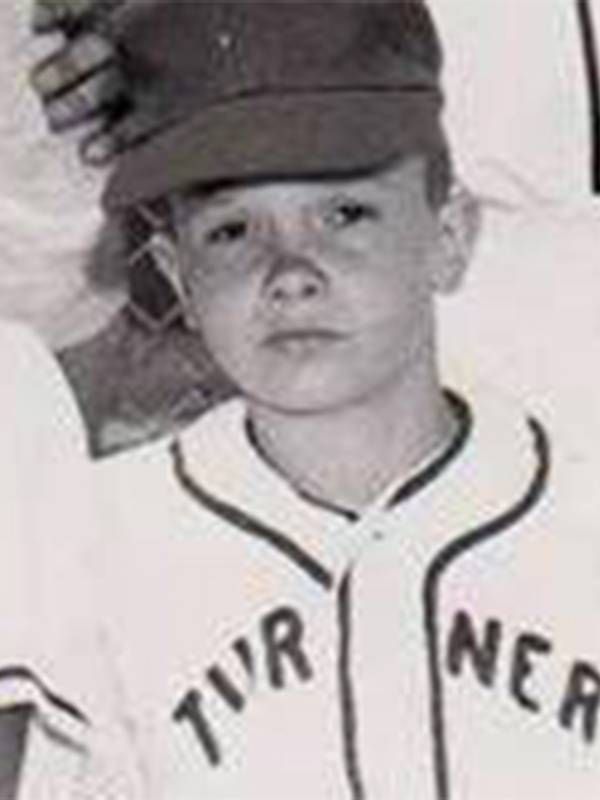

Steve was a gregarious, fun-loving and compassionate kid who loved animals. He loved going to our family's church so much; his first aspiration was to be a Lutheran minister. He was living the suburban American Dream in 1950s and '60s middle America, playing sports and teasing his sisters.

I was 11 years younger and only have a few memories of the younger Steve. I do remember the smell of his aftershave when he'd chase me down, tickling me until I cried. When he wasn't home, I'd wrap myself up in his letterman's jacket. Steve was a big brother — a tormenter, but above all, my champion and protector.

When Steve grew further into his teen years, he developed the rebelliousness and angst that visits most of us. After skipping school and finally dropping out during his senior year, Steve enlisted in the Army in 1969. He was 17.

He tried out for the Army baseball team and also wanted to become a paratrooper, but was ultimately taught how to fire large Howitzers from foxholes near ChuLai, Vietnam.

When Steve moved back into my parents' home after his service, he wasn't the same person. He was sullen and much darker. His carefree, happy side showed less often, but he was just as sensitive and generous. Steve instilled in me a love for music and bought me a cassette player and Cat Stevens' "Teaser and the Firecat" for Christmas the year I turned eight.

After Vietnam, He Wasn't the Same

Steve's drinking increased and he would sit up many nights playing classical music with loud, crashing drums and symbols. As a naïve child who knew nothing of the horrors of war, I asked him once if he'd killed anyone. "I guess I did. I don't know and maybe that's what bothers me the most," he said.

In 1981, Steve had failed several stints of employer-sponsored rehab and lost his job. He left our family home for good, embarking on a 17-year cycle of binge drinking and drying out in VA hospitals. He'd work until he started drinking again and lose his apartment.

Wash. Rinse. Repeat.

For our family, it was constant worry and hoping he would take the help we thought the VA was providing and stop the endless cycle. For our mother, the guilt of signing the papers that allowed him to enter the military in the first place weighed on her.

No matter how far Steve fell, his love for reading and learning never ebbed. Books were just as much of a necessity for his life as his backpack of clothing.

In the times he was working, he always stayed in contact with our mom, even sending her money sporadically. He never failed calling on her birthday, Mother's Day or Christmas. If he was near our hometown of Kansas City, he came to family functions.

No News Was Terrible News

In the fall of 1999, Steve stayed with our nephew and then headed north to look for work. The last he spoke with our mom, he had an apartment in Fargo, N.D. and was working on construction crews.

When Steve didn't call our mother a couple of months later on her birthday, she feared something was wrong. Four days passed until Christmas and she knew something was wrong. Another birthday and Christmas passed before I decided to see if I could find out what happened.

Telling our mother her only son was dead was one of the hardest things I've ever had to do. Steve's cycle had begun again after we'd spoken to him that final fall. Almost 30 years to the day he enlisted in the military, he'd lost his apartment and died alone, from alcohol poisoning and hypothermia in an alley in Fargo.

Although his body was transferred to the VA for a military burial, neither the civilian nor VA officials looked for next-of-kin to notify.

As a family, our worst fears had become our reality. Not only was Steve gone, but he died and was buried with no one. He was treated in death as an invisible person.

When the Fargo and Kansas City press ran stories on Steve, we realized in life, there were people like my friend who saw Steve. A nurse from the VA wrote me a letter telling how she remembered Steve because of his big smile, intelligence and wit. She commented he was always carrying a book.

A pastor, a man who helped homeless people secure housing, even a guy who remembered Steve from playing football in high school 30 years before on an opposing team, all remembered my brother.

Seeking Answers About My Brother's Life

To help process my grief and maybe find answers for my mother on what went wrong in Steve's life, I secured over 300 pages of medical records from the U.S. Department of Veteran's Affairs (VA). It was evident by that documentation Steve was likely never properly diagnosed or treated.

Not only was Steve gone, but he died and was buried with no one. He was treated in death as an invisible person.

The symptoms of Post Traumatic Stress Syndrome (PTSD) were apparently evident from Steve's first admission to a VA hospital in 1981. After writing that they thought he had PTSD, what was documented next was truly astonishing. A doctor asked Steve if he thought he suffered from PTSD. Steve said he didn't think so. And that was the end of that.

For the next 17 years, Steve was treated for an unnamed "personality disorder likely present before his service." In my research, various people who worked with Vietnam veterans in particular told me this was a common VA diagnosis during that era.

There are an estimated 38,000 homeless veterans on the streets of America on any given night, many of them self-medicating, as Steve did. A VA study that analyzed veteran suicides from 1979-2014 estimated the number of veteran suicides to be 22 each day.

There is hope. Both the number of homeless veterans and veteran suicides has been steadily decreasing in recent years.

There are no memorials for veterans like my brother, or the one my friend encountered, who have fallen through the cracks. They don't need a memorial, though; they just long to be seen. If you see a veteran this Veterans Day, or any day, please recognize they deserve a "thank you."