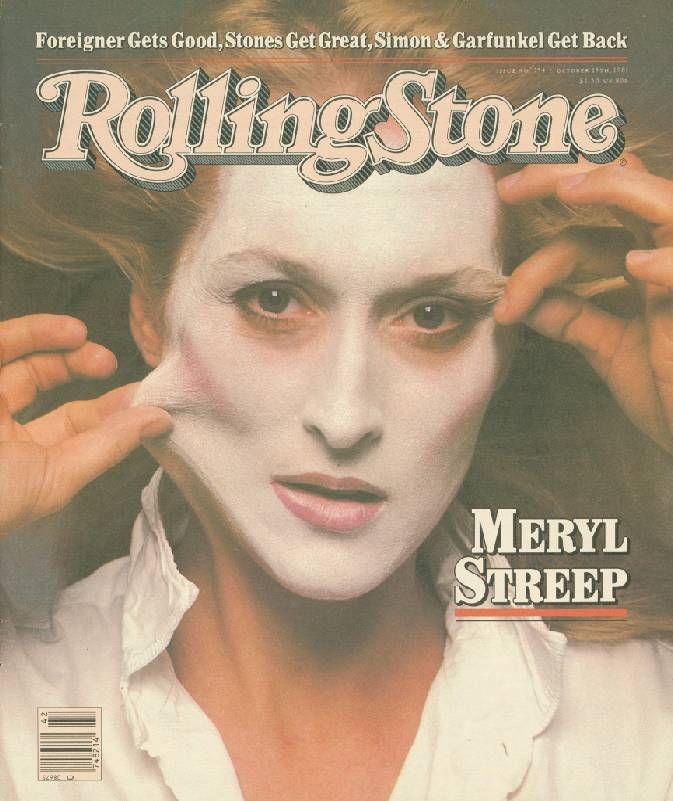

Rocking Back with Rolling Stone's Jann Wenner

In a chat with Next Avenue, the counterculture bible’s founder and now bestselling memoirist talks freely about sex, drugs, rock and roll buddies — and aging

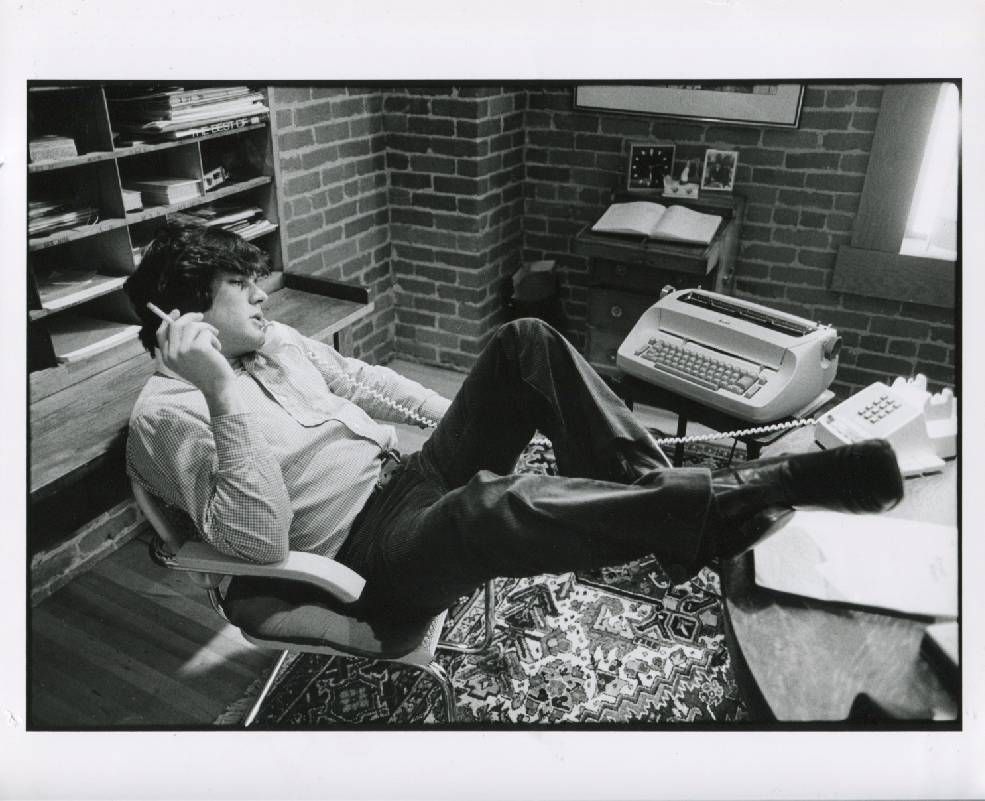

If you grew up in the '60s or '70s, odds are you were a Rolling Stone reader. You also likely knew about Jann Wenner, the brash wunderkind who founded the magazine in San Francisco at 21 in 1967, The Summer of Love.

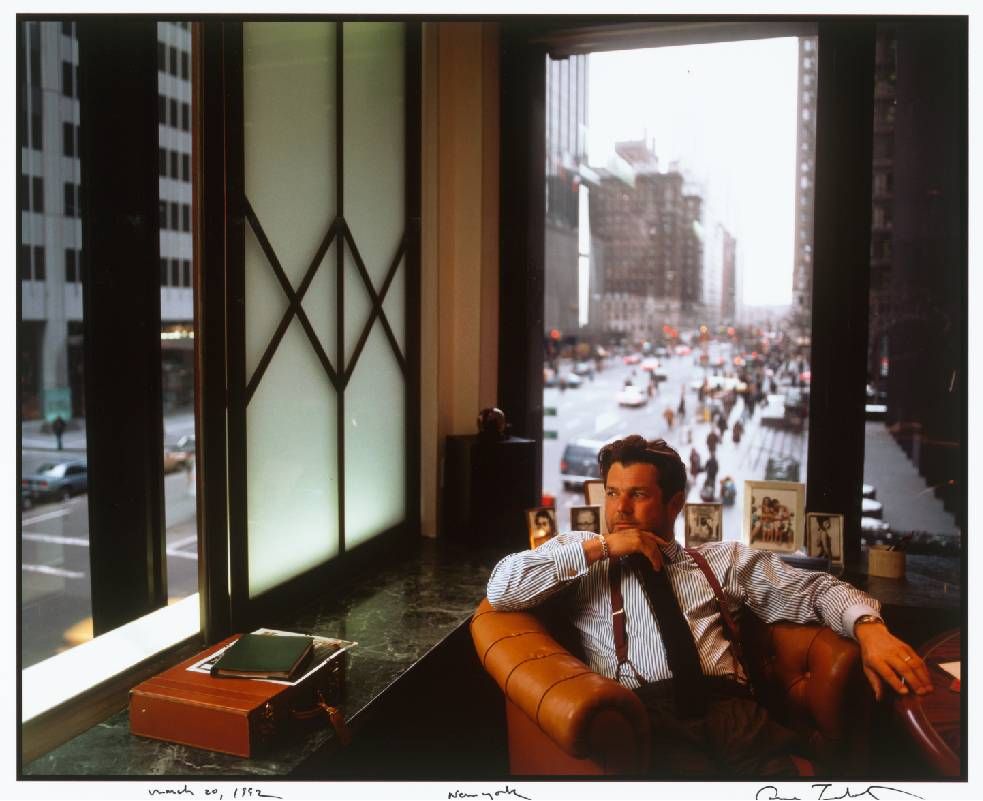

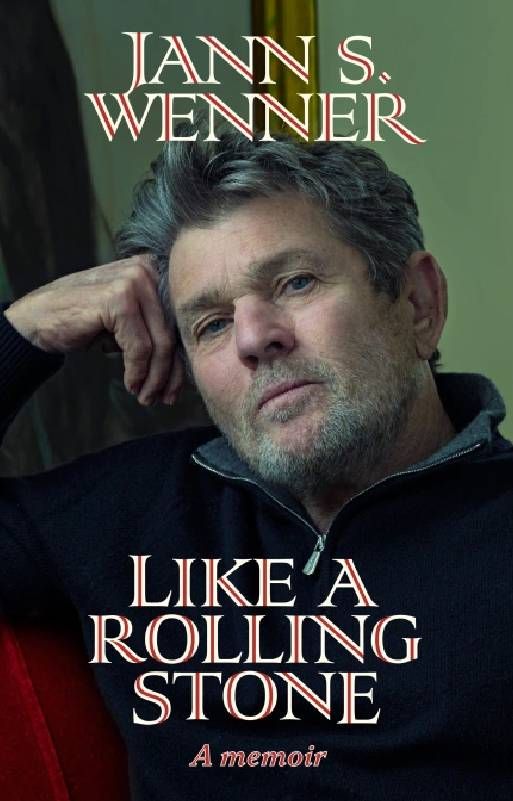

Now, Wenner is 76 — born in the first year of the baby boom — and he's out with a rollicking, frank 576-page, bestselling memoir, "Like a Rolling Stone." (When I interviewed him by Zoom in his New York City apartment, Wenner told me the first draft was more than twice the final length.)

I found Wenner thoughtful, funny, self-effacing, revealing about his celebrity friends (from Jagger to Jackie O) and candid about his drug use and cocaine in the Rolling Stone office.

"The legacy part, honestly, I'm not interested in that. Legacy schmegacy."

Aging, as well as a fall and a recent string of surgeries (heart, femur, spine) that led to a brief coma have made Wenner more mellow and reflective.

Wenner — who changed his name from Jan to Jann at 15 to be cooler — grew up in the San Francisco suburb of San Rafael with his entrepreneur parents, Sim and Edward, and two sisters. He dropped out of Berkeley and soon started Rolling Stone with rock music critic Ralph Gleason.

Wenner later created Outside, Men's Journal and Family Life magazines, bought Us magazine and co-founded The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. He sold his company in 2017; his son Gus is now Rolling Stone's CEO.

Wenner's personal life has been unconventional. He was married to Jane Schindelheim for 28 years and the couple had three children. During the marriage, in 1995, Wenner began a serious relationship with the fashion designer Matt Nye, who he later married; the couple have three children.

Highlights from our conversation:

Next Avenue: How's your health? I know you've had a few tough years.

Jann Wenner: My health right now is terrific. I think primarily because I'm just kind of happy overall and I'm enjoying not working. A lot of tension is drained out of my life, which is delightful.

You wrote that your health problems were your fault. Why did you say that?

Look, health problems are very related to age and I'm 76, so there's that. But the exacerbation of them is related to the fact that I had diabetes and that I smoked for 40 years. [Wenner coughed periodically during the interview.]

You're walking with a cane?

Mainly out of safety. I can walk without the cane, but I think we all know as we get older that falls are to be avoided.

Why did you want to write your memoir and why now?

Once I recovered from my heart attack and various injuries and sold Rolling Stone, I had all this time on my hands. And it was a project that I knew had to be done. I thought to myself this story of building Rolling Stone and my own story were nicely combined to be a story of our times in our generation.

The book is also a way of leaving your legacy, right?

The legacy part, honestly, I'm not interested in that. Legacy schmegacy.

Some people called you an enfant terrible at Rolling Stone, but I think that described you as a child. What were you like as a kid?

I was the brightest kid in the class and ready to start trouble and couldn't contain myself.

That paid off, though.

After a lot of patience on other people's parts.

One thing I didn't know until I read your book was that you're Jewish. Has that affected your life and who you are today?

I think not in an outward sense, not being a practicing Jew. I was raised in Marin County, California, and went to boarding school and those were not very terribly Jewish environments. I am certain that there's a genetic and intellectual part of that identity that's very strong.

You describe your mother as a different kind of mom and wrote that somewhere along the line you realized you didn't like being around her. You called her a mixed blessing.

My mother was very strong and funny and independent and an individual that really stood out. She was kind of a role model for [my sisters and me]. Then as we got to be adults, and she kind of abandoned our family and went off on her own, sometimes she'd be very selfish. Sometimes she was very loving, too.

And your dad?

My dad was a more conventional guy who did everything he could to hold the kids together. He was a great guy who took a lot of joy in all the craziness that he had in his kids.

There's a poignant part of the book when your father was on his deathbed, you were in your early 40s and thought about telling him you were gay, but didn't. Why not?

Well, I thought: Why should I introduce it on his last moments on earth? That would be extraordinarily selfish.

"I don't know that it would have thrived in that more high-pressure environment of New York. I don't think we'd have been as close to the artists and as authentic as we were."

Do you think your parents knew when you were a kid that you were gay?

I think so, yeah.

You never came out publicly the way some celebrities have. Why?

To me, it's a private matter. It became inevitable given the New York media environment that people were going to write about it. But I wanted to discourage it. I mean, just let me have my personal life.

When you started Rolling Stone, you borrowed $7,500 from your family and parents of your soon-to-be wife. What was that like?

I don't think anybody really thought it was going to succeed that much, but they were willing to just take a gamble.

You began Rolling Stone in San Francisco, where you were, not New York City, where most magazines were. Why?

We were so much of the San Francisco scene. And I didn't know anything about the magazine business; I didn't know it was located in New York.

I don't know that it would've thrived in that more high-pressure environment of New York. I don't think we'd have been as close to the artists and as authentic as we were.

Eventually, you and the magazine moved to New York. You wrote that you failed to anticipate how New York would change the magazine and you. How did it change Rolling Stone?

We became more of a national voice in a national publication than you would otherwise have in an area like San Francisco.

How did moving to New York change you?

Well, success goes to your head, and you get involved in a swirl of distractions, which is lots and lots of fun. And then you get lionized, then people start thinking you're pretty hot s*** and then you start thinking you're pretty hot s***. Then, you come too close to the sun.

You write about Rolling Stone's Capri Lounge, the darkroom where some staffers dabbled and dealt in drugs, especially cocaine. Do you regret allowing cocaine in the office?

Well, I don't regret it in that something horrible was done. I mean, cocaine was just in the air everywhere in those years. It dominated the music scene.

I don't think the use of cocaine was productive. There was a lot of wasted time and money on it. Did it make anything good happen? Not particularly.

I bet a lot of Next Avenue readers in their 60s were some of your earliest readers. How has Rolling Stone been a touchstone for boomers?

The baby boom was the largest single age cohort in American history … As soon as this generation gets to come of age, it starts to confront a lot of realities about America that are really discomforting … We're in a war in Vietnam for f***'s sake.

So, naturally we respond to Dylan and the other sounds of rock trying to express this frustration, the hypocrisy of the society and what the reality is ...

Rock and roll became what we called 'the glue that held the generation together.' And for that reason, Rolling Stone became one of those touchstones.

Rolling Stone has published many fantastic articles. Any you're especially proud of?

There's so many of 'em, it's hard to say. But I thought Hunter's [Hunter S. Thompson] coverage of the 1972 presidential campaign was brilliant. And I thought Tom Wolfe's 'The Right Stuff' and 'Bonfire of the Vanities' are also great.

How did you get Tom Wolfe to write 'Bonfire of the Vanities' in installments in Rolling Stone?

Well, I was a fan of Tom Wolfe's before I started Rolling Stone. So, it was always on my mind that I wanted to have Tom write for us … I just set about finding him and started courting him …

"Rock and roll became what we called 'the glue that held the generation together.' And for that reason, Rolling Stone became one of those touchstones."

We both had this big fascination with American culture and the edges of it and the oddities of it. And I think he liked being a little bit a part of our daring, rebellious, challenging spirit.

Was the idea to publish 'Bonfire' his idea or your idea?

The idea for the subject was my idea: New York City.

The idea of doing it in installments was totally his idea based on how novels were published in the late 19th century in England — in installments every week in newspapers.

A journalist I know told me he thought your greatest contribution to the culture was creating a platform for talented people who didn't fit into the establishment of journalism like Hunter S. Thompson and photographer Annie Leibovitz. What do you think?

I think that's true … We were the desired home of all the new talent that was coming up much the way The New Yorker had been a couple of decades before.

Were you concerned your friendship with rock stars would create a conflict of interest for Rolling Stone?

No, because I understood the potential for it, and it wasn't really a problem.

When Altamont happened [the 1969 music festival where a concertgoer was murdered during The Rolling Stones' performance], the question was how we were going to handle it vis-a-vis my friendship with Mick.

I made the decision we would go journalistically with what we saw as the truth. And while Mick got angry about that at that time, we resumed our friendship, without another word about it, later on.

Honestly, no friend of mine ever asked me for a favor, to alter something or give extra stars to [the reviews of] their records.

You don't write much in the book about women in rock you've known. Why?

Well, there's not that many women in rock, especially then. Who were the women in rock then? Janis Joplin, Tina Turner, Grace Slick comes along later, Bonnie Raitt, Linda Ronstadt, Stevie Nicks much later.

The point is that rock and roll bands were guy bands. They were like motorcycle gangs or guitar cowboys. It was not a woman's field.

But I also felt you didn't have friendships with women in rock the way you did with the guys.

Well, I did have a decent relationship with Stevie Nicks. Janis was very short-lived; she was an alcoholic and an angry person. Bonnie, I had a good relationship with over the years. And Linda lived in LA.

I was close to people who are my mates.

You wrote that Rupert Murdoch asked if you would sell Rolling Stone to him, but you didn't. Then in the late '70s, you turned down another offer to sell Rolling Stone for 12 million dollars. Do you wish you had taken these?

Oh, I'm so glad I didn't. Because I was having so much fun and I had a long ways still to go.

You eventually sold Rolling Stone to Penske Media in 2017, 50 years after starting it. Was it that the time was right or were you forced into doing it?

All those things. I had always thought after 50 years, I'm going to bow out. And my son was ready to take it over. I also had the health scare, so I just didn't want to do it anymore.

And the internet was closing in, reducing our profit margins so much that we were just in a shrinking business. It was time to go. It had to be in the hands of a larger company that could afford the costs of it.

Did you expect that Gus would one day take over the magazine?

I thought he was going to be too young to do it by the time I had been there 50 years. But he came in right after college and showed such an aptitude, that after a year, I started to say, 'All right, let's proceed as if you are going to take this over and start learning the business.'

Do you see a lot of yourself in him?

Oh yeah. [Laughs.] He's full of energy and drive and belief in himself and charming and a great salesman and sharp. But he's a much more disciplined, methodical guy than I am.

"Mick's an extremely smart, very charismatic individual who has to be pretty guarded as a person to keep a sense of privacy."

You wrote that when he took over, you wanted to continue having a relationship with 'your baby,' and wondered if you could be the uncle or the grandpa or the brother-in-law. But you ended up being 'the ex-wife.' What happened?

Just exactly that. They didn't want me around anymore. They wanted to do it themselves and they were right. Who wants this old guy around all the time? He's a pain in the ass.

You're very upfront in the book about using cocaine, LSD, pot and heroin. And that you had peyote chocolates with your oldest sons and Matt in 2008. What's your view about drugs today?

I think that pot is obviously harmless and the moves lately to legalize and decriminalize it are absolutely way overdue. I encourage its use.

I think psychedelics are going to be proved extraordinarily useful and productive for mankind. I think they have the potential to rescue the country and civilization.

Heroin is heroin; it's addictive. Obviously, you're not going to live your life very well with that.

Do you consider yourself retired these days?

Well, I hate that word 'retired,' but I don't know what's better to say.

I have a couple of lunches a week with old friends and it's great. I've got three teenagers in my house, so that keeps me very young. And I've got the three older kids.

I definitely still feel like that [Bob Dylan] song: 'Forever Young.'

What gives you meaning and purpose now?

I'm finding a lot of meaning and purpose just in personal happiness and family. And these are things that I put aside to some degree during that very intense period running the business.

I assume you've given up motorcycle riding and bicycle racing. Have you found anything to replace them?

Well, with one bum leg, I don't want to risk a fall, so that eliminates everything [physically] except weight training and a stationary bike at home and stuff like that.

Some people take up painting or a musical instrument.

Painting sounds good.

I'm enjoying reading and listening to music; I'd like to do something a little more active than that, too; I'm going to go see the LA Philharmonic tonight at Carnegie Hall doing Mahler's First Symphony. I'm loving that kind of music.

Finally, what is your advice on aging?

Watch your health as much as you possibly can. Live every day. Spend time with friends. And for God's sake, be happy.

Jann Wenner's Famous Friends

Next Avenue: I want to ask about a few rock stars and celebrities you've been friendly with. Tell me about Mick Jagger.

Mick's an extremely smart, very charismatic individual who has to be pretty guarded as a person to keep a sense of privacy. He's smart, funny and fun to hang out with. He's been a dear, good friend and a pleasure to watch perform. An impressive character overall.

Bob Dylan?

Funny, sharp, really intelligent, a very deep guy who keeps to himself. But if he likes you, you're in like Flynn. Bob likes to play games, and so sometimes it's game playing — just having fun.

John Lennon?

John was more on all the time. He was very witty, obviously extremely intelligent, passionate about music and also had a deep kind of mean streak because he was pissed at a lot of things that had happened to him. But overall, an extraordinary person to be around.

My sense from the book was that you didn't stay friends.

After we did the 'Lennon Remembers' interview in Rolling Stone, I published a book from it. He didn't want me to, so he was pissed off. After about five years, we buried the hatchet and he started to call the interview 'Lennon Regrets.'

In 1970, you went to see the new movie, 'Let It Be' in an empty theater with John, Yoko Ono and your wife Jane. What was that like?

Totally strange. That 'Let It Be' movie really portrayed the imminent breakup of The Beatles. When it was over, it was such a sad moment. We all left the theater and went out on the sidewalk and hugged each other and cried.

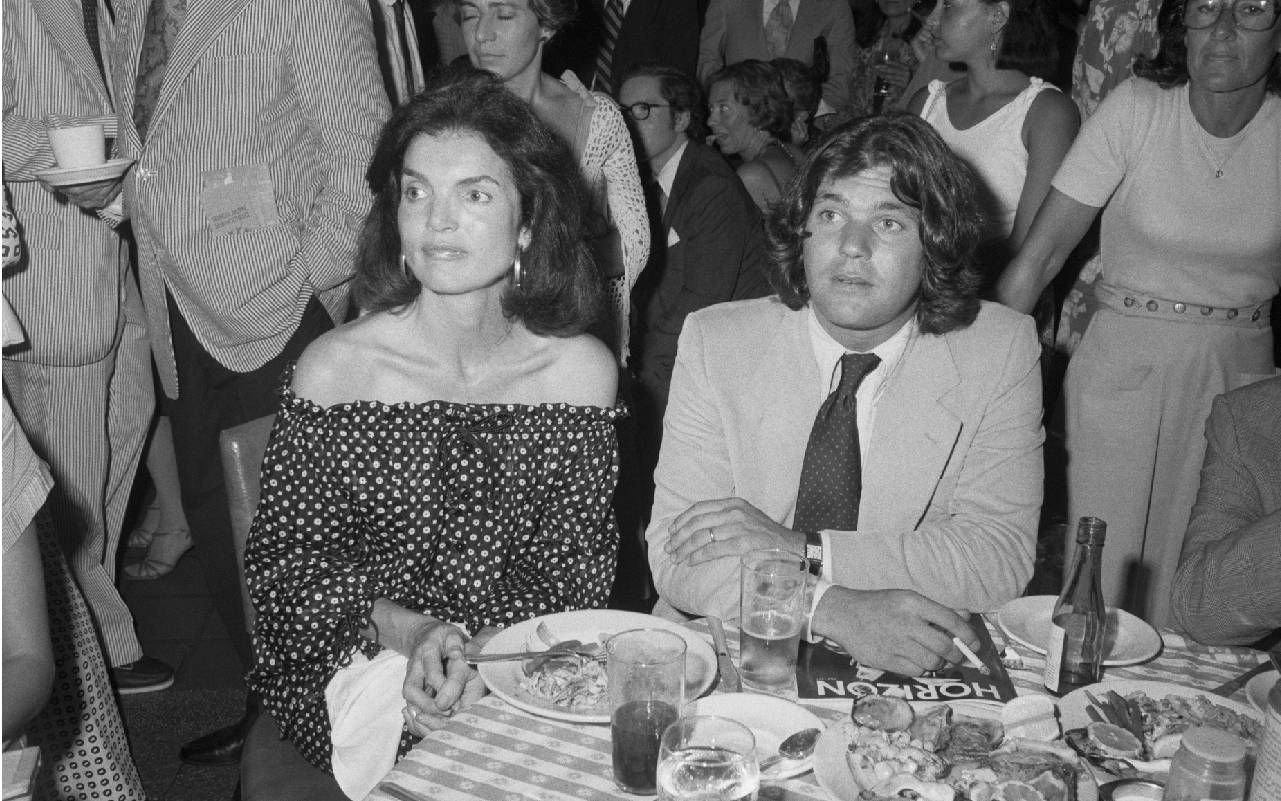

You also write about your friendships with Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis and JFK Jr. What were they like?

Jackie was just the most wonderfully iridescent personality; funny and thoughtful and personable.

And John was just a good kid I always kept my eyes on.