Roz Chast is Candid About Caregiving

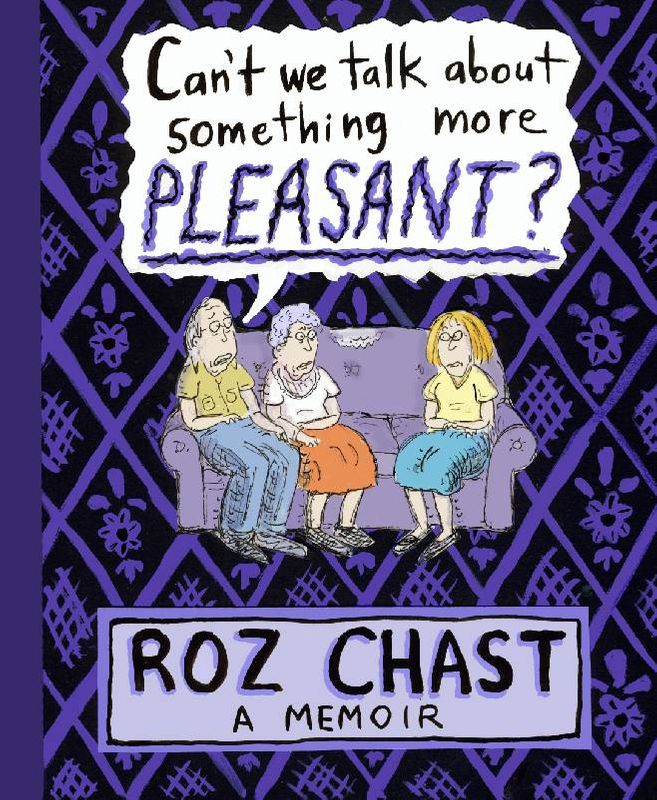

The New Yorker cartoonist writes with humor and honesty about caregiving for her late parents, who lived into their 90s, in her graphic memoir ‘Can’t We Talk About Something More Pleasant?’

Cartoonist Roz Chast's father, George, died in 2007 at age 95 and her mother, Elizabeth, in 2009 at age 97. Even with the passing of time, Chast still refers to the years she spent as a caregiver for both her parents as "a very strange and bewildering series of events."

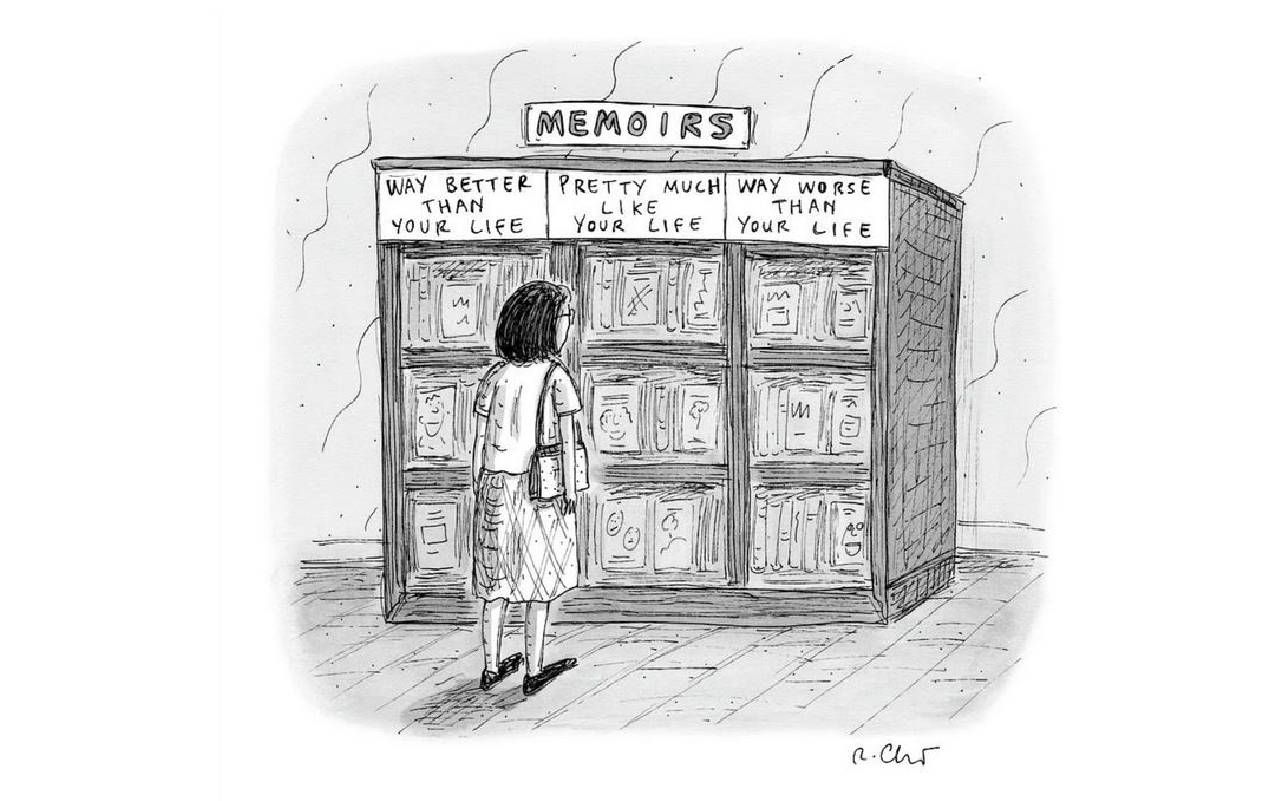

It's a period of her life documented in "Can't We Talk About Something More Pleasant?" a graphic memoir that is at turns hilarious and heartbreaking, featuring Chast's inimitable cartooning style familiar to readers of The New Yorker, where her work has regularly appeared since 1978.

Her father George was developing dementia and her mother, Elizabeth, was initially felled, literally, by acute diverticulitis.

Originally published in 2014, Chast's memoir, which was a National Book Critics Circle Award winner and a National Book Award finalist, is the featured title for April's NEA Big Read in the St. Croix Valley (near St. Paul, Minnesota where Next Avenue is based) and also for the NEA Big Read in Wichita, Kansas. Both initiatives will spotlight a series of events including book discussions, art exhibits and presentations surrounding the challenges we all face when it comes to the subject of caregiving.

Chast offers a clear-eyed and candid look at every facet of caring for aging parents; her father, George, was developing dementia and her mother, Elizabeth, was initially felled, literally, by acute diverticulitis, which materialized not long after a fall in what Chast describes as the "Crazy Closet."

This was the space that served as the "attic" in the Brooklyn apartment where her parents lived for 48 years. Items included broken manual typewriters, blankets, purses, luggage, textbooks, board games and fly swatters. (Her mom had been doggedly looking for a memento – that Chast wasn't interested in - from a trip to the Galapagos Islands.) As Chast writes: "They could not throw anything away."

A Book for Every Part of the Caregiving Journey

Caregiving isn't necessarily a planned stage of life. As much as we all know our parents will age, and that we will age, we don't know what aging will look like or what types of health crises will impact the lives of those we love. "Can't We Talk About Something More Pleasant?" offers the insight of lived experience for someone just beginning a caregiving journey, someone right in the thick of it, or someone who can look back at the highs and lows of caregiving for loved ones now gone, and nod knowingly.

As I told Chast during our recent interview, I received her book from my brother after our mom died at 91, almost eight years ago. Our father died 26 years ago. There were levels of caregiving involved for both of our parents, more so for our mom, and as I told Chast, there are many parts of her memoir, both funny and poignant, that definitely resonate with me.

"When I was taking care of my parents, many of my friends weren't at that stage [with their own parents] yet," said Chast, who is an only child. "As I've gotten older, more people I know are going through it now. There's kind of a relief that it isn't in front of me."

Chast details in her memoir that, as she noticed her parents becoming frailer, she began spending more and more time with them, frequently making trips from her Connecticut home to Brooklyn, often bearing bags of groceries. Her mother was still feisty (and funny) and her quieter father was gradually fading away.

She was a sounding board for the financial and legal issues the Chasts didn't want to face – a segment entitled "The Elder Lawyer" is particularly amusing as Elizabeth regales her daughter with tales of "the Mellmans":

"Before they died, they signed all their money over to their daughter. Next thing you know, she puts them into a nursing home [Chast's drawing of the nursing home is called 'Trail's End']...and she buys a DRAWERFUL of CASHMERE SWEATERS!"

No Cashmere Sweaters

Chast goes on to write that she'd heard "about a dozen versions of this story over the years…it was sad to think about them imagining me waiting in the wings and licking my chops." Chast learned about everything she never thought she'd need to know about – their rent, pensions, various bank accounts (a subplot about George's bankbooks is both humorous and sad) — and obtained power of attorney. The section ends with her noting: "I did not buy a drawerful of cashmere sweaters."

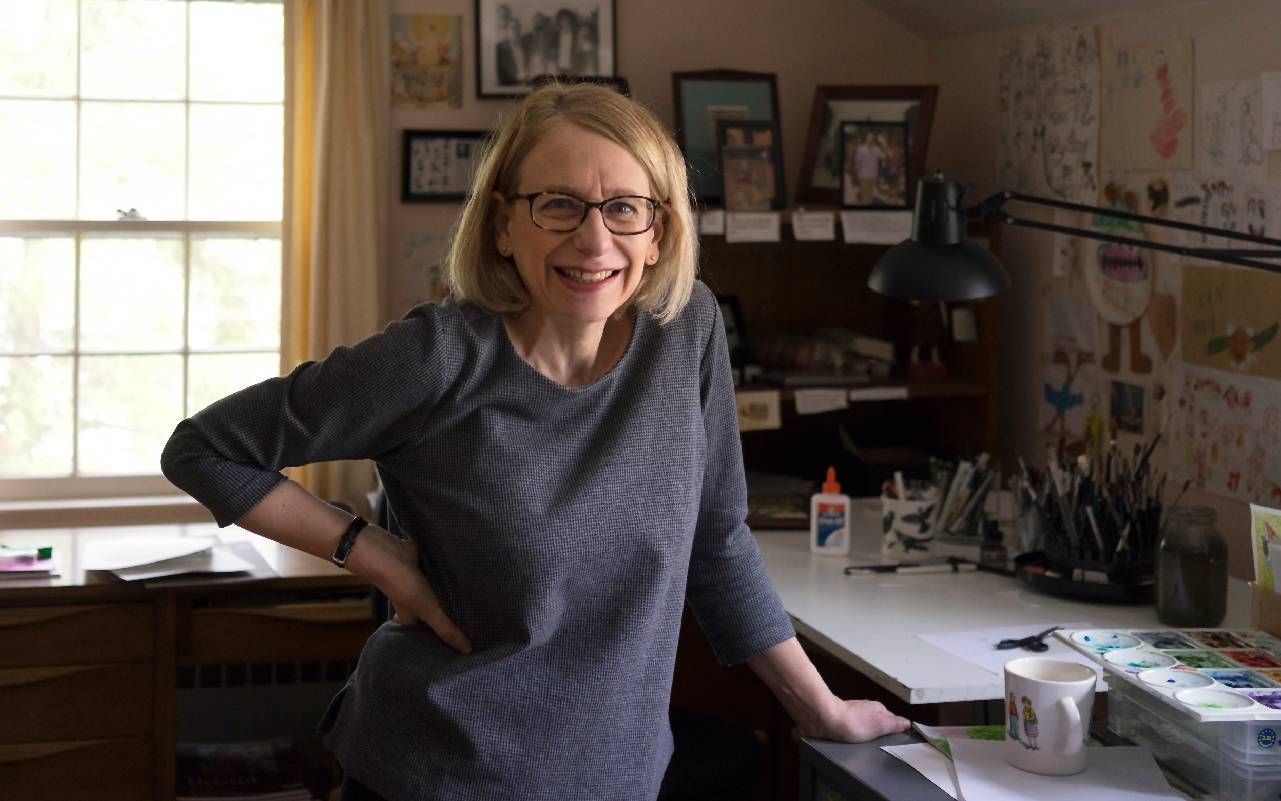

In addition to keeping meticulous detail of caregiving expenses (both parents spent time in assisted living facilities, required hospitalization, and in the case of Elizabeth, had hospice care and a full-time aide named Goodie), Chast kept a different kind of personal record, using her art to process her increasing levels of stress.

"It's what I do in general with my work – I sort out an emotional issue by writing or drawing about it," she said. Chast's memoir concludes with a series of beautiful drawings of her mom in her final moments and immediately after her passing. The brash Elizabeth from the book's early pages has been poignantly transformed.

In addition to drawing, Chast would correspond via email with close friends to share in detail about what was happening with her parents.

"When I started working on the book, all I'd have to do is put topics like 'mom neurologist' into search, and I'd find what I was looking for," she said.

Photos Instead of 'Stuff'

Another section of "Can't We Talk About Something More Pleasant?" contains a series of photos that Chast took of her parents' apartment after they moved into an assisted living facility.

There are photos of her father's Schick razors, her mother's eyeglasses, the "Crazy Closet," George's "work station" piled with stacks of paper, even the inside of the refrigerator with Elizabeth's "cheese-tainer," her invention which consisted of a turquoise bin covered with tape that held…cheese.

"I knew I didn't want to take a whole lot of stuff, but I wanted to document things, like the old piano which could never stay in tune," Chast said. "I have all the photos on my phone, and I do pull them up from time to time."

Items she did keep include some of her mother's silver pins, her father's reference books filled with magazine and newspaper clippings, and a piece of Indian pottery that she writes "my mother once told me was 'valuable.'" Chast paid to have everything else taken away.

An Honest Look at the Challenges

Chast does not shy away from being honest about how difficult caregiving can be. A page entitled "Gallant and Goofus: The Daughter-Caretaker Edition" highlights the conflicting emotions a caregiver faces: the Gallant daughter "treasures the time spent with her parents, because she knows that soon, they'll be gone. Goofus admits, "Mostly, when with her aged parents, wishes she were somewhere else."

Letters from many readers since the book's publication have amazed Chast as they share how her experience touched a chord and has been helpful in their own family situations.

"When you are a caregiver, there's isolation, sadness, mixed feelings, bewilderment and sometimes you think you're the only one having those feelings," she said.

One reader in particular helped Chast. In the beginning of the book, Chast writes about a baby girl who died before Chast was born and of whom her parents never spoke. They never told Chast where she was buried.

An Uncanny Twist

"A woman contacted me through my website and asked if I had ever looked for her on FindAGrave.com," said Chast. At that point, Chast still had her parents' cremains in two containers in her closet, unsure of what to do with them.

Chast was able to locate the baby's grave in a cemetery in Queens, New York and subsequently learned that her mother's parents were buried there as well.

"My parents had never talked about this cemetery," Chast said.

In an uncanny twist, there was one sole cemetery niche, near where the baby had been buried, that was available.

"It was niche J2," said Chast. "My parents' apartment in Brooklyn was 2J."

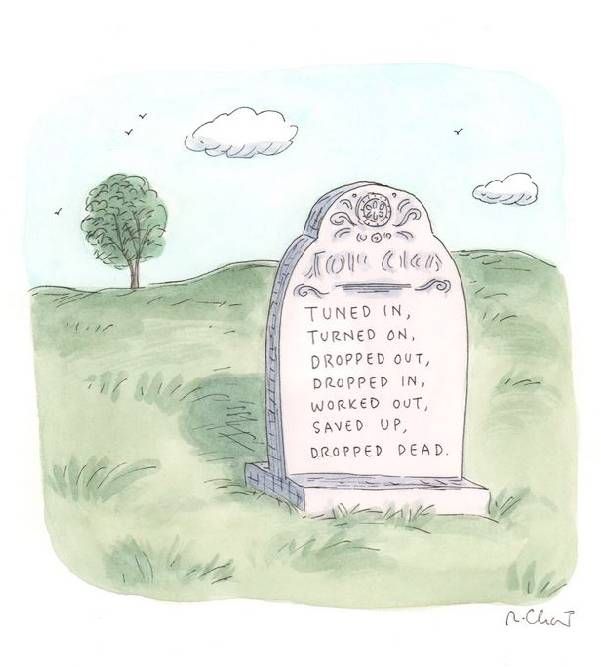

Now 68, Chast laughingly calls her own aging "an ongoing project." She feels lucky to be in good health ("nothing is surprisingly painful," she laughs again) but her experience of watching (and helping) her parents age into late life is on her mind.

For many caregivers, there are lingering memories, and Chast shares that sentiment.

"After my mom died, I had to get rid of the flip phone I had. I took so many calls from my parents, doctors and nurses on that phone. My ring tone was 'Für Elise' and after they were gone, I just couldn't hear that anymore," Chast said. "No, no, no."