Sad Irony Turns Scientist Into Wife's Caregiver

Bill Neaves studied Parkinson's, then watched his wife develop a related illness

(A longer version of this article ran previously on Flatland, the digital magazine of KCPT Public Television in Kansas City, Mo.)

Churchgoers at a tidy, white-steepled United Methodist Church in Carrollton, Mo., heard a frank admission from their guest pastor one spring morning in 2007.

“When asked to preach this Sunday, I almost said no,” Priscilla Wood Neaves told the congregation.

She had, in fact, fought for the right to preach. As a girl growing up in the 1950s in the Texas panhandle, Neaves was told that women could not be ordained ministers in the United Methodist Church. The information was erroneous, but not until she left Texas for college, marriage and motherhood did Neaves encounter a female pastor who could disprove it.

Eventually, Neaves graduated from the Perkins School of Theology at Southern Methodist University, became an ordained Methodist minister and hospital chaplain and gathered a wealth of life experiences to frame her sermons.

And then life dealt a blow that temporarily stilled her voice.

“I was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease three years ago,” Neaves told the congregation in Carrollton, “and I have not formally ‘proclaimed the Word’ since then. I guess it was because of feeling a mixture of fear and anger directed toward God.”

From Texas to Missouri

Listening in the congregation to the candid and unusual sermon was the preacher’s husband, Bill Neaves. Few in the country church knew that, while Priscilla was wrestling with her medical diagnosis, Bill was engaged in a professional and political struggle involving the search for cures for diseases like Parkinson’s.

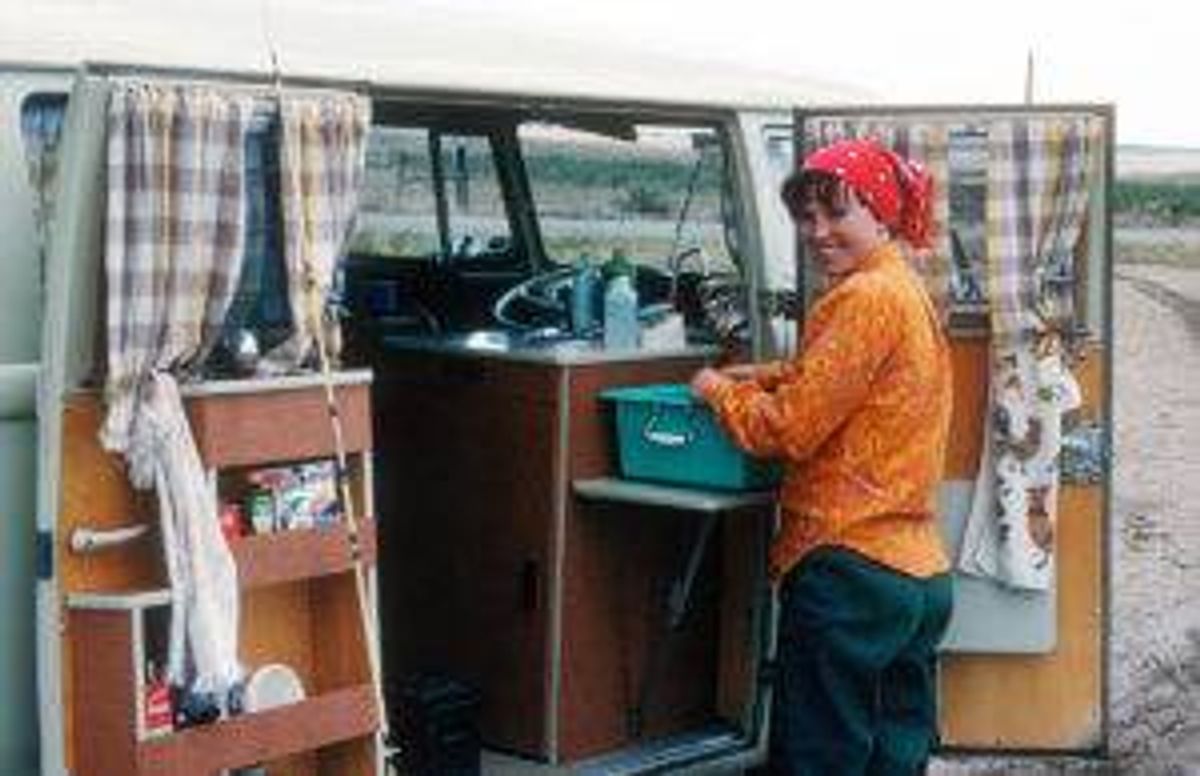

Childhood sweethearts from Spur, Texas, Bill and Priscilla Neaves both packed up briefcases stuffed with credentials when they moved to Kansas City in 2000.

He had been dean and executive vice president for academic affairs at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas. She was a chaplain at Children’s Medical Center Dallas.

James Stowers, founder and CEO of American Century Investments, had consulted with Bill Neaves about a research facility he was creating in Kansas City. He envisioned a place in his hometown where premier scientists would have resources and time to study the causes of diseases and embark on a search for cures. Stowers asked Neaves to be the first president and CEO of the Stowers Institute for Medical Research.

“I was enthusiastic about it,” Neaves says. “Few people want to support basic science.”

Priscilla quickly dived into life in Kansas City by joining the board of directors of the medical ethics research and advocacy group now known as The Center for Practical Bioethics. She also joined the Institutional Review Board for Children’s Mercy Hospital.

'Something Was Off'

The first signs of trouble appeared in the fall of 2003. Priscilla didn’t feel well; something was off, she said. She wasn’t able to walk with her normal stride.

In January 2004, a physician at the University of Kansas Hospital diagnosed Parkinson’s disease. Another doctor at Washington University Medical Center in St. Louis concurred.

As Priscilla noted in her sermon a few years later, the news came as a blow. Parkinson’s disease is a neurodegenerative disorder that hinders the brain’s ability to produce dopamine, the transmitter that enables people to regulate motor functions.

Still, the disorder progresses slowly in most people, and Priscilla was accustomed to a busy and productive life. She became a full-time volunteer chaplain at Carroll County Memorial Hospital in 2006 after the couple purchased a farm about 60 miles northeast of Kansas City. In that capacity, she provided spiritual resources and facilitated support groups for cancer and Parkinson’s patients.

A Scientist and an Advocate

Though his wife’s health was a concern, Bill Neaves was ebullient about progress at the Stowers Institute in its early years. First-rate scientists had indeed been willing to come to Kansas City, and they were engaged in rigorous and productive research.

One cloud on the horizon was legislation that kept resurfacing in the Missouri General Assembly. Pushed by Matt Bartle, a lawyer and at the time a state senator from Lee’s Summit, its stated purpose was to ban human cloning. But Bartle’s definition of cloning went far beyond a scenario in which a squawking baby might emerge from a laboratory. His bill aimed to ban even the copying of human embryos as small as a few dozen cells.

Scientists believe the newly created cells can be used to repair tissue, organs and nerves damaged by all manner of injuries and diseases. In the early 2000s, they eyed the laboratory procedure with great hope.

To Bartle and others, it represented a moral threat. That’s because, once embryonic stem cells are harvested, the tiny embryo that sheltered them is destroyed. What some people viewed as a somewhat mysterious lab dish procedure, religious conservatives saw as the willful termination of human life.

The issue made it to the November 2006 ballot in the form of a constitutional amendment that would protect all scientific research in Missouri that was legal under federal law.

Bill Neaves was in the thick of it all. He wrote essays and traveled the state, speaking to groups to explain what embryonic stem cell research meant for science and the Stowers Institute. He touted its potential to stop or slow the suffering from devastating diseases. He mentioned Parkinson’s disease. What he never said publicly was that the person closest to him had been diagnosed with that illness.

The constitutional amendment passed by a razor-thin margin — a difference of 50,800 votes out of 2.1 million cast.

Ultimately, science itself stepped in to bring an uneasy truce. A Japanese researcher found a way to make adult cells behave like embryonic cells, with the same capacity to repair and rebuild damaged body parts.

Progression of the Disease

With his wife at his side, Bill Neaves had done his part to stand up for science. But science could not immediately return the favor. It could not stop the frightening changes that were going on in Priscilla’s body.

The previous couple of years had been difficult. The couple lost their son, William Jr., in May of 2007. Living in Houston, he had waged a long struggle with alcoholism and died of its complications. “Priscilla was amazingly stoic about it, but I know it must have been incredibly difficult for her,” Bill says now.

Priscilla continued her work as a voluntary chaplain and frequently preached sermons in the chapel of Carroll County Memorial Hospital.

“When questions about the meaning and purpose of life hit us like a tornado, God’s grace can be most tangible,” she told her small congregation in 2009. “Job’s way can also be ours. I know. I have been there.”

Priscilla’s symptoms were increasingly resembling more of a dementia-type illness than traditional Parkinson’s disease. At the end of 2011, specialists at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., found that Priscilla was suffering from cortical Lewy body disease — a brain disorder closely related to Parkinson’s but even more devastating. The destruction proceeds beyond motor control to destroy brain neurons associated with cognitive functioning and movement.

Attitude of Acceptance

Bill Neaves recalls that his wife absorbed the terrible news calmly. “Priscilla was still pretty much intellectually intact then, and I was very impressed with what she said,” he recalls. “The neurologist said, ‘This is what we have, and it will probably be fatal within a year and a half.’ Priscilla said, ‘Well, glad to know what I’m facing, and I know firsthand that a lot worse things have happened to people than what is happening to me.’”

Priscilla’s disease was progressing rapidly. By 2012, she was experiencing anxiety, confusion and paranoia. Daily tasks such as routine teeth brushing became a struggle.

On the advice of her family physician, Priscilla moved to a Leawood facility that treats patients with dementia. She became bedridden, mostly paralyzed from the chest down, with limited use of her hands. Once a passionate voice on nearly every topic, she now spoke only intermittently.

For nearly a year, Priscilla was officially in hospice care.

Bill, who describes himself as “a compulsive-type person,” began preparing for his wife’s death.

A Turnaround

And then the mysterious, maddening, wonderful creation that is the human body served up another surprise. At the end of 2013, Priscilla’s disease stopped progressing. It had run its course, a specialist told Bill. With good care, she could live for a long time. But the damage already done — the paralysis, the speech loss, the loss of memory and cognition — was likely irreversible.

If life had presented a different set of circumstances, Bill Neaves might be traveling the world right now, speaking at scientific conferences and soaking in the tributes due the founding president of a world-class research facility.

“I’m really glad I don’t have to do that anymore,” he tells me.

“Not that I wouldn’t rather be sitting on our deck looking over the trees at the Beartooth Wilderness in Montana with Priscilla, enjoying a glass of chardonnay, but this isn’t … isn’t bad,” Neaves says. “It’s better than I thought it would be. There’s still enough of Priscilla there to make it feel very rewarding to have the time with her.”