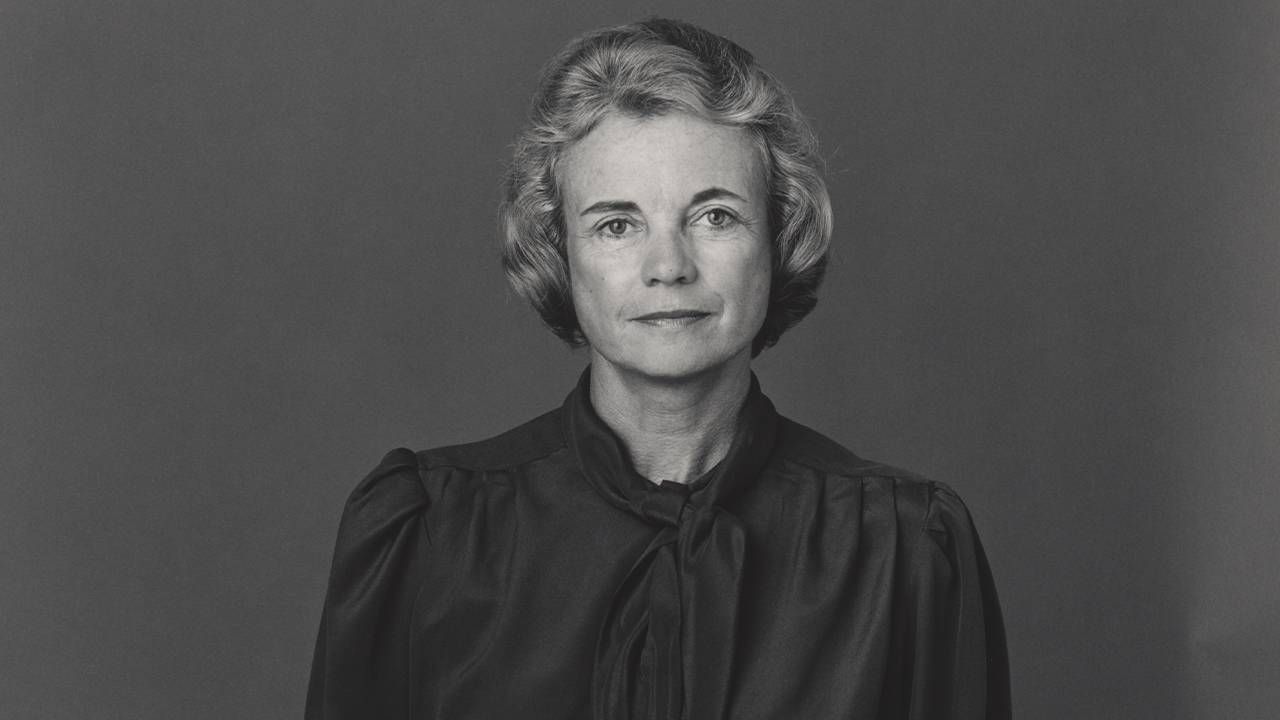

Sandra Day O'Connor: The Trailblazer

A new PBS documentary looks at Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O'Connor whose appointment was ‘about women everywhere’

Last month, when Kathy Hochul became the first female governor in the 244-year history of New York State, you might have expected a bit more hoopla. But since 45 women have served, or are currently serving, as governors of other states, the era of female gubernatorial firsts isn't what it once was.

It was a far different story 40 years ago this month. When Sandra Day O'Connor was sworn in as the first female justice in the 191-year history of the Supreme Court of the United States, there was too much hoopla as far as she was concerned. The cover of Time magazine read, "Justice — At Last."

Sure, it was a historic appointment, O'Connor told journalist Charlie Rose years later, saying "but…everywhere that Sandra went, the press was sure to go." Indeed, there were more requests for press passes to the O'Connor confirmation hearings than to the Watergate hearings. Never before had there been gavel-to-gavel TV coverage of a judicial confirmation hearing.

Among all the glass ceilings broken by women, none had created as much buzz as the nomination of O'Connor to the high court.

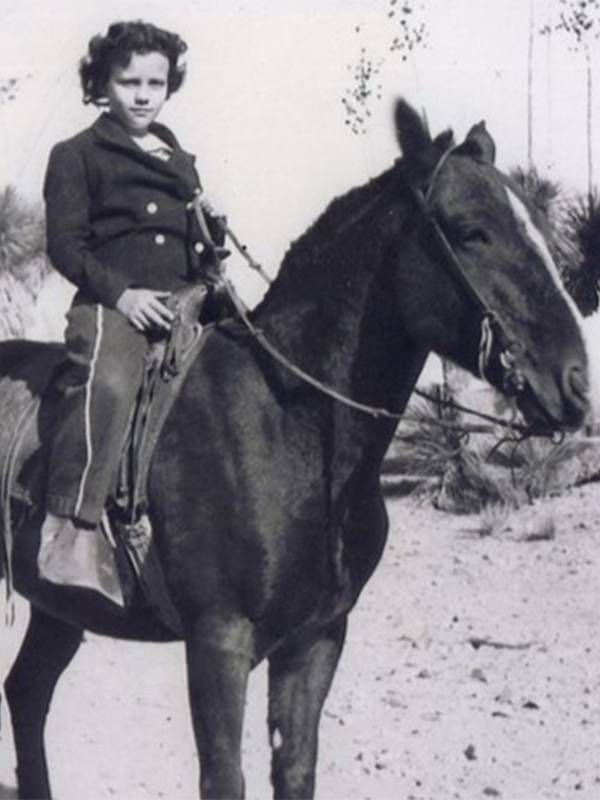

Among all the glass ceilings broken by women, none had created as much buzz as the nomination of O'Connor to the high court. After all, here was a self-described "young cowgirl from the Arizona desert" who never could have imagined becoming the first female justice at the highest court in the land.

"She was the perfect first," declared Linda Hirshman in the American Experience documentary, "Sandra Day O'Connor: The First", premiering Monday, September 13 on PBS at 9 p.m. ET/8 p.m. CT. The two-hour broadcast is based on the book "First," the biographical portrait of O'Connor by journalist Evan Thomas.

"She could carry both roles — the conventional female role that made her not scary and the tough-minded judicial role that made her powerful," said Hirshman, author of "Sandra Day O'Connor and Ruth Bader Ginsburg Went to the Supreme Court and Changed the World."

Confirmed, Then Tested

It was politics — the growing gender gap— that drove Republican Ronald Reagan, who opposed the Equal Rights Amendment, to make this promise during the closing days of the 1980 Presidential campaign: "One of the first Supreme Court vacancies in my administration will be filled by the most qualified woman I can possibly find."

Promise kept. Just months into his first term as president, Reagan selected O'Connor, a state Appeals Court judge from Arizona who had no federal judicial experience, who wasn't known for her deep familiarity with constitutional law and was put to the ultimate test — cramming for her confirmation hearings.

"Can you imagine?" Thomas asks. "I know she lost ten pounds, so she was really cracking it. They had a whole team around her feeding her stuff."

Supreme Court Chief Justice John Roberts was then a young Justice Department lawyer whose job was to supply O'Connor with her briefing books for the hearings. "But she went through them faster than they could supply them," Thomas told me.

O'Connor would be confirmed unanimously, 99-0 (Montana Sen. Max Baucus was absent), but don't think for a second it meant the Supreme Court culture was ready to accept women as equals.

During her first oral argument, in fact, O'Connor started to ask her first question from the bench and the lawyer at the podium said, "Let me finish," not showing proper deference to Court protocol or the newest justice. That evening in her journal, O'Connor wrote, "I felt put down."

Then there was the memo Chief Justice Warren Burger gave her when she arrived. It was a psychological study about what happens when a woman enters a group of male leaders.

"The report found that it was unsettling, off-putting, to the male leaders, and therefore the woman should be passive," Thomas tells American Experience.

Oscie Thomas, who collaborated with her husband on "First," found the memo Burger gave to O'Connor, along with his note to her in her papers at the Library of Congress.

"It was pretty stunning...the Chief Justice was trying to keep her in his pocket, so to speak, count on her vote, make her beholden to him in his own awkward way. I think it probably backfired," she said.

'No Excuses'

What may have helped O'Connor survive as the only woman among the nine justices is how she learned independence and self-reliance, growing up on the 160,000-acre Lazy B cattle ranch in southeast Arizona. Among her responsibilities was delivering lunch to the ranch hands.

They had T-shirts made. One said "I'm Ruth, not Sandra" and the other "I'm Sandra, not Ruth."

"She loaded up the old Willys Jeep with lunch," O'Connor's oldest son Scott recalled for the PBS program, "and started out for the rendezvous point where the cowboys were going to be branding the calves…and she got a flat. Here she is, all of fourteen or fifteen years old, and had to change a flat tire on a four-wheel-drive Jeep in the middle of nowhere, without any help and get onto lunch."

Oscie Thomas added, "She was very proud of herself when she achieved this. She gets out to the roundup. She says, 'Dad, I had a flat tire and I fixed it.' Her father says, 'You're late. Next time, leave earlier.'"

O'Connor's dad "wasn't very gentle with her but it was something that stayed with her, important for her later life," Oscie Thomas told me.

Evan Thomas punctuated the philosophy of O'Connor's dad: "No excuses, no excuses. Just do it."

Two Women, Different Roles

Those dozen years before O'Connor welcomed the second woman to the Supreme Court were lonely. Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg's arrival meant the Court would finally build a ladies' room near the Court conference room.

And it didn't matter that the two women looked nothing alike; Supreme Court advocates still got confused. So they had T-shirts made. One said, "I'm Ruth, not Sandra" and the other "I'm Sandra, not Ruth."

One major difference between O'Connor and Ginsburg was their role on the Court. Ginsburg was a reliable liberal vote, while O'Connor was often the swing vote, a label her youngest son, Jay O'Connor, told me really bothered her.

"It implied she was swinging back and forth, from one side to another, intentionally trying to play that role. Her vote counted no more, no less than other justices," he said.

But Supreme Court observers like journalist Jeffrey Toobin have called O'Connor "the most consequential woman in American history" because her vote, the fifth in many key 5-4 decisions, "saved abortions rights, preserved affirmative action and her vote gave Bush the presidency in Bush v. Gore."

O'Connor had come a long way from her days as a Stanford Law grad when she applied to 40 law firms for a job but got only one interview. The question: "How well do you type?"

An Unexpected Career Shift

O'Connor met the man who would become her husband at the Stanford Law Review. John O'Connor would later leave his Phoenix law practice to move to Washington, D.C. where he joined a law firm and accompanied his wife on the social circuit as she made history on the Supreme Court.

But by 2003, John O'Connor's Alzheimer's was so advanced that Justice O'Connor brought him to her chambers. He couldn't be left alone. Two years later, she announced she was stepping down from the Supreme Court to care for her husband. She wanted to support John the way he had supported her.

"But it took such a long time for her replacement to get lined up that by the time that she actually stepped down from the court, Dad's condition had declined so much that it was time for him to go into an assisted living facility," Jay O'Connor said. "That meant that she wasn't going to be able to be as helpful day-to-day in the caregiver role to him. So the reason for her retirement was not going to play out as she saw. She had some sadness around that. But she's always been a person who doesn't look back to try to rethink decisions. That's been a characteristic of her whole life."

A clue to what O'Connor would do after her Supreme Court years actually came 10 years earlier when she invited then-Senate Majority Leader Tom Daschle and Minority Leader Trent Lott to her chambers and chastised them for the lack of civil discourse in our politics.

By 2009, increasingly worried that American schools were failing at teaching civics, O'Connor founded the nonprofit, iCivics (where I consult) to use video games to teach children how our government works in the hope they will become engaged citizens. Each year, iCivics games and resources are used by 140,000 teachers and nine million students.

O'Connor often reminded students that the first public schools were started to teach civics to youth. "The practice of democracy," she said, "is not passed down through the gene pool. It must be taught and learned by each new generation."

Justice O'Connor used whatever forum she could to preach the gospel of civics, even appearing on "The Daily Show," telling host Jon Stewart that "only a third of Americans can name the three branches of government, much less say what they do…but 75 percent of Americans can name at least one 'American Idol' judge."

'She Forged A New Trail'

Nearly three years ago, Justice O'Connor, now 91, issued a public letter that she had been diagnosed with dementia and was stepping back from public life. But she used the moment when she knew she would get the country's attention to reiterate her hope "to make civic learning and civic engagement a reality for all."

"I want students to learn how their government works and how, in essence, they're part of what makes us function."

As counterintuitive as it may be, the first woman on the Supreme Court said, "iCivics is my most important legacy. I want students to learn how their government works and how, in essence, they're part of what makes us function."

In 2009, when President Obama awarded O'Connor the Medal of Freedom, the highest civilian honor, Jay O'Connor says his mom used her private moment with the president to urge "we find ways to get back to civility, civil discourse, especially in Congress." Twelve years later, O'Connor says his mother would be "horrified" at just how far our politics have sunk.

President Obama likened Sandra Day O'Connor to the pilgrim in the 19th-century poem she often quoted, called "The Bridge Builder."

"She forged a new trail and built a bridge behind her for all young women to follow," said Obama.

O'Connor once told Stanford graduates that President Reagan's decision to pick her to make history at the Supreme Court wasn't about her. "It was about women everywhere. It was about a nation that was on its way to bridging a chasm between genders that had divided us for too long."

A bipartisan group of Senators and Representatives has recently introduced legislation to place statues of O'Connor and Ginsburg in the U.S. Capitol or on the Capitol grounds. Currently, only 14 of the 266 sculptures in the Capitol are women.