'She Votes' Tells the Intersectional History of Suffrage

A new book celebrates the women who fought for the right to vote 100 years ago

Art historian Bridget Quinn, author of the recently published primer on the history of women's suffrage She Votes, wasn't always a voter herself.

As a young woman, she had what she characterizes as a "punk rock" attitude toward the American political system. In fact, she was so vocal about her anti-voting views that when she announced she would be writing about voting rights, a friend called her out on Facebook for previously abstaining from the practice.

After teaching art history for two decades and writing a book called Broad Strokes: 15 Women Who Made Art and Made History (in That Order), Quinn's political views are still radical — but she's changed her approach.

"I understand from personal experience that the two-party system has huge problems. But it is the system we have," Quinn said. "So, it is vital to vote in a way that is meaningful, because the incremental changes do build up. And then, after you cast that vote, you can do everything possible to move the needle on the ground. But to not vote is to just abdicate all (your) power."

Today, suffragists' signs are echoed by those held aloft at Black Lives Matter marches and even the Shepard Fairey paintings that popped up during the 2008 presidential election.

Today, Quinn thinks that voting is the "issue that is going to make or break our democracy."

As the U.S. marks the 100th anniversary of the passage of 19th Amendment, on August 18, Quinn's She Votes revisits the history of the women's suffrage movement in an attempt to explore critical figures and moments that have largely been forgotten.

This history is also reimagined throughout the book in illustrations by 100 women artists.

Visual Art as Political Activism

During the Women’s March in 2017, Quinn noticed that artfully crafted signs and banners were a crucial element of the protest. Indeed, visual interpretations of radical movements go hand-in-hand.

Just 100 years ago, she explains, women were tortured and force fed in prisons during hunger strikes, "just for standing outside of the White House with a sign."

Today, suffragists' signs are echoed by those held aloft at Black Lives Matter marches and even the Shepard Fairey paintings that popped up during the 2008 presidential election.

Quinn's experience at the Women's March strengthened her conviction that a book about suffrage would pair well with illustrations — especially because today we live in what she calls a "visual universe," in which we communicate through pictures (whether that's Instagram or emojis) as much as through words.

"I also personally feel like any time you make art, that is activism," Quinn said. "It's a way of speaking up in the world."

Illustrating the History of Suffrage

In order to make the connection between art and activism, the book's publisher, Chronicle, reached out to 100 women artists and assigned each one a different topic from the book to illustrate.

The illustrations were often pegged to historical figures, many of whom don't show up in traditional history textbooks.

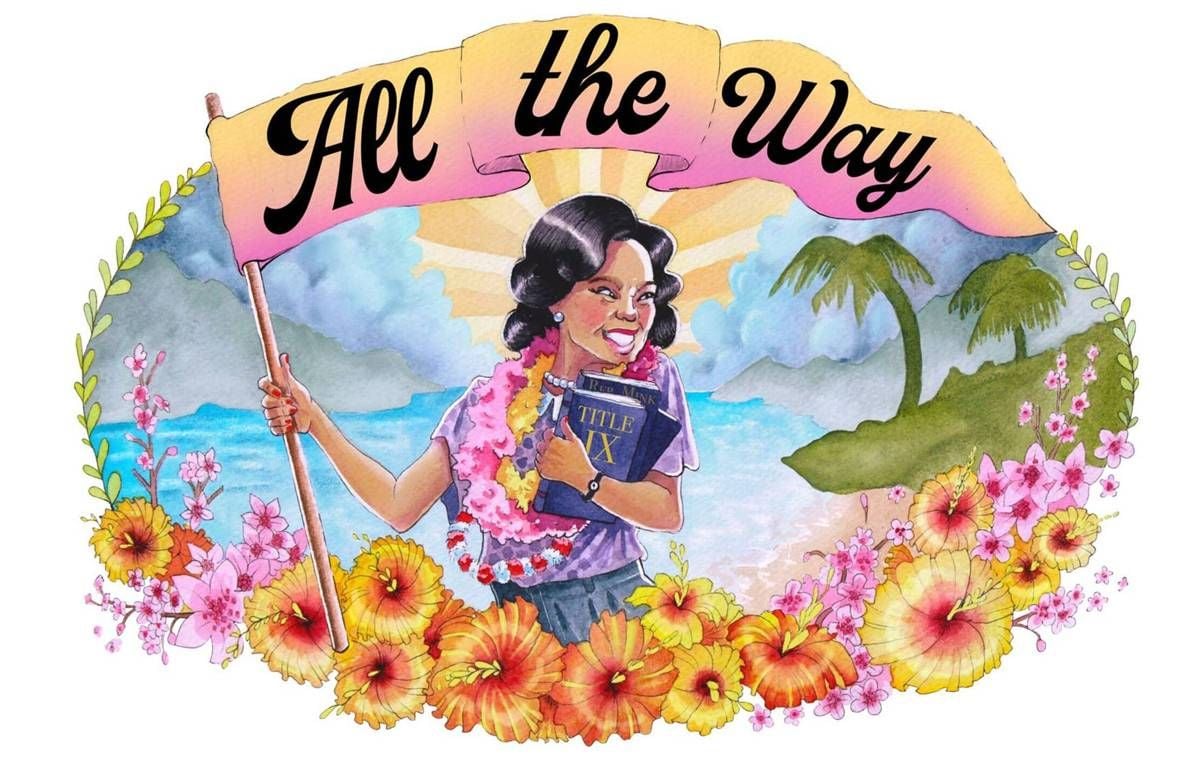

For instance, Quinn details the achievements and legacy of Wilma Mankiller, the first woman to serve as principal chief of the Cherokee Nation; Patsy Mink, the first woman of color elected to Congress and Josephine Langley, the Blackfeet woman who taught basketball to the girls at her Montana boarding school.

She also features some of their more widely known peers, including Ida B. Wells, who founded the first organization dedicated to suffrage for Black women; the abolitionist and women's rights activist Sojourner Truth and radical anti-racist and gay liberation activist Audre Lorde.

"I wanted to retell women's rights history in the United States so that you have this overview," Quinn said. "These dry or academic stories need to exist and I'm glad they exist. But that's not what I'm trying to do. Using visual art as a way of sparking interest makes things seem less like eating your spinach."

The Artists of She Votes

Chronicle tasked Brooklyn-based illustrator Tashana McPherson with creating a portrait of Sojourner Truth. McPherson, who illustrates mostly Black women with a focus on their hair, depicts a poised Truth in her signature striped vest and bonnet set amidst a backdrop of vivid pink, orange and blue flowers.

"I wanted to evoke quiet strength, and I saw that she lived in a place where there was a lot of nature. So, I just wanted to surround her with nature," McPherson said. "I wanted her to be sitting strong but serene."

The Jamaican-born McPherson immediately connected with the book's subject matter: After settling in Miami with her parents and sisters, she received her citizenship at 17, and registered to vote in Florida, where she cast an absentee ballot for Barack Obama in the 2008 election.

That idea of an understated power came up again when Taiwanese-American artist Maggie Chiang explained the inspiration behind their illustration for the book.

In their image, hills resembling breasts topped by blazing bonfires are set against a rich, midnight blue sky. The scene is a recreation of the funeral ceremony held for Wilma Mankiller.

"The words that come to mind are 'quiet empowerment,' especially with the fires on the mountain tops," Chiang said. "Each fire is a beacon, or a symbol of commemorating (Mankiller)."

Chiang says that participating in the book gave them a way to "uplift other women and support women's rights and equality."

Creating an Intersectional History of Suffrage

Diversity, and by extension intersectionality, is a core principle of She Votes.

Quinn acknowledges that "it's so easy for women's stories to get erased in history," especially when it comes to the Black women who were excluded from the movement by some of its white leaders.

She hoped that she could offer a corrective to that narrative by making sure that women of color were front and center as both its subjects and the women who contributed to its creation.

"All kinds of women throughout the history of women's liberation in the United States have been active, successful and prosperous in their communities," Quinn said. "To pretend otherwise is to just buy into a story line that was created explicitly by Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton. Their disappointment, frustration, fury and fear drove them to say and do terribly racist things."

Still, she adds that Anthony and Stanton aren't necessarily the villains of her book. Quinn simply wants to tell a "clear-eyed" and complete version of history that gives readers the information they need to draw their own conclusions.

"The more stories that I can tell, the more I feel like I'm putting a flag in the ground for those people," she said. "The book is really a celebration. I really want it to be a joyful experience."

Any history of suffrage will by necessity include moments of strife and suffering, stories of women who died in obscurity despite their awe-inspiring achievements or before the fruits of their hard work could be realized — and She Votes is no different.

But that is at least part of where its power comes from: the realization that through decades of consistent crusading, speech-making and on-the-ground activism that is still ongoing, women and their non-binary, genderqueer and trans compatriots are making equality a reality.

"I just hope people take away that we can still keep fighting and don't feel that if you're not equipped that you can't do it," McPherson said. "Because look at all these different women from whom it was almost impossible for them to do anything, and they still got it done."

(This article originally appeared on Rewire.org.)