How a Slavery Legacy Made This 65-Year-Old a Georgetown Undergrad

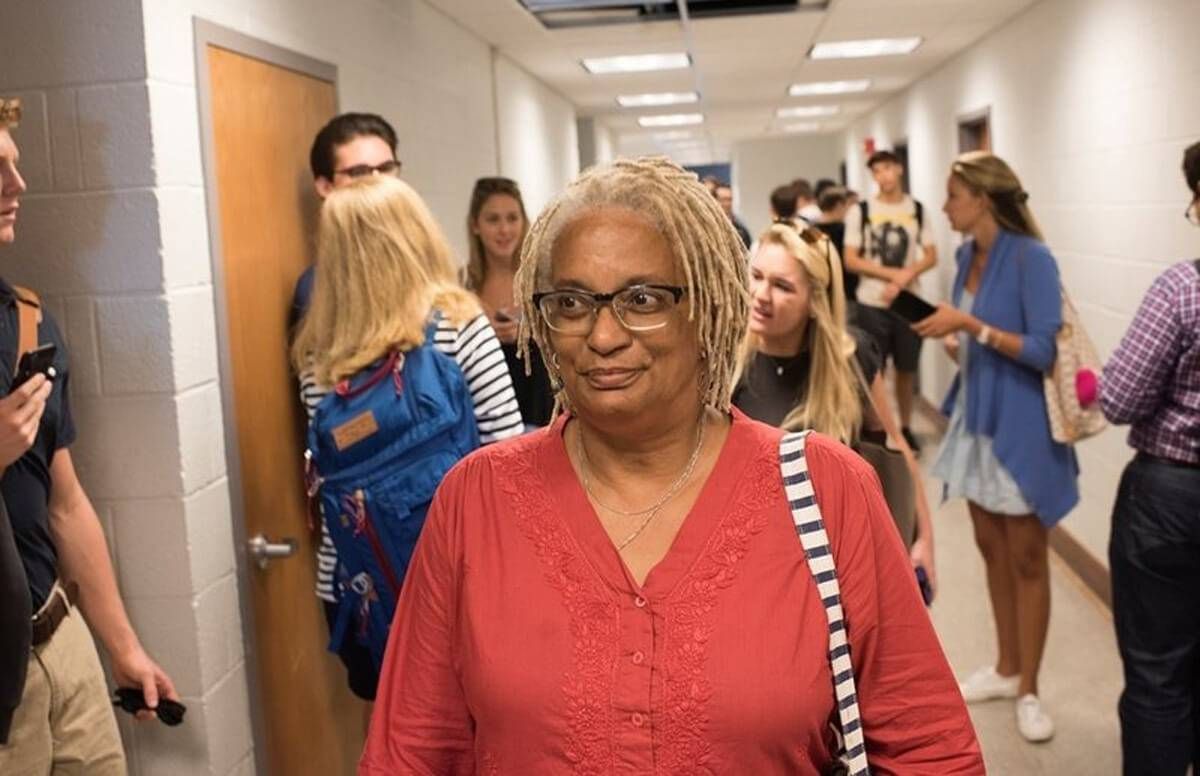

The new life, on campus, for Melisande Short-Colomb

It’s been nearly 14 years since Hurricane Katrina washed away all the physical mementos of Mélisande Short-Colomb’s life along the Mississippi Gulf coast. Her nearly 200-year-old Pass Christian, Miss., house and everything in it was gone in an instant — the family Bible, every photograph, document and piece of furniture, including the rocking chair with the baby bite marks that had been in her family for generations.

“Nobody was hurt. But we were all hurt. We survived,” says Short-Colomb, 65, the emotional scars still quite visible. She was raised in a multi-generational house — grandparents and four great-grandparents when she was born.

As sudden and devastating as it was to lose those family keepsakes, Short-Colomb says it was a more recent “Oh my God!” moment that would fill in unexpected details of her family tree. And in the process, it set her on a new life path. She’s now a rising junior at Georgetown University, in Washington, D.C. How — and why — that came to be:

Receiving Georgetown's Legacy Status

Years ago, Short-Colomb’s grandmother had shared stories about her ancestors being enslaved. In fact, her grandmother was only the second generation born past slavery. But it wasn’t until Short-Colomb received a question from a genealogist on Facebook three years ago that she’d discover her family members had been enslaved by the Jesuits at Georgetown and later sold to a Louisiana plantation as workers in the sugar cane fields.

"I tell the students here — I try not to call them kids — that I am not the age of their parents. I'm the age of their grandparents."

“I grew up with photographs and physical things around me that were representative of the lives of my family before me — rice baskets and machetes and the implements of working in the cane fields,” Short-Colomb explains. “My grandmother’s grandmother was the youngest child of a 16- and 17-year-old who were born in Maryland and sold to Louisiana in 1838. My grandmother was born on the land that was the plantation that her family was enslaved on.”

Short-Colomb recounted her family history last week in her dorm room on the fourth floor of Georgetown’s Copley Hall. She had applied to Georgetown and was accepted two years ago after the school offered legacy status to the descendants of the 272 slaves.

From the moment Short-Colomb set foot on campus as one of the few descendant legacy students, she has immersed herself in the school’s GU272 Advocacy Team. It lobbied for the non-binding student referendum that made headlines in April 2019 when two-thirds of Georgetown students who voted supported a $27.20 fee each semester. If the university approves, the money will go to the direct descendants of the 272 people Georgetown sold in 1838. Short-Colomb prefers calling the fee “a reconciliation act” instead of “reparations.”

The Oldest Undergrad on Campus, By Far

Short-Colomb is the oldest undergrad by far in the Class of 2021. “I tell the students here — I try not to call them kids — that I am not the age of their parents. I’m the age of their grandparents,” she says.

She brings a lifetime of experience to campus. The mother of four and grandmother of two dropped out of Xavier University, worked as a construction site inspector, went to culinary school and spent many more than two decades as a chef.

Her advice to the students: “Be what you’ve wanted to be since you were three and not necessarily what your parents want you to do.” Short-Colomb adds: “I also tell them by the time you’re 35 or 40, you may want to do something else. Don’t limit yourself.”

What She Tells Other Students

Short-Colomb says she speaks to her fellow undergrads in ways their parents don’t. “I say, ‘I’m not invested in you. You’re not my kid. I don’t have any expectations of you. I just want you to be your best person.’”

Short-Colomb says there’s at least one advantage to being a 65-year-old undergrad: “I see so many young people here under stress, having to achieve and make the grade for their parents. And I don’t have any of that. I’m doing this for the sheer pleasure. It was a leap of faith for me to apply as a 65-year-old and a leap of faith for the university to admit a 65-year-old.”

Short-Colomb says that when she first got to campus, she felt like an alien, but not alienated.

“I was surrounded by 18-to-22-year-olds who looked at me like I was a professor or chaplain. Everybody was moving faster than me,” she recalls.

Making Adjustments on Campus

And there were intense physical issues. “No one told me the school was on a hill. It was exhausting at first,” Short-Colomb says.

The adjustment was difficult in another way, too.

Not long after arriving, Short-Colomb was getting breakfast in the cafeteria when she heard someone in the back of the kitchen call “Chef!” She recalls: “I stopped and turned around as if to answer, because someone was talking to me. In that moment, it was like ‘Oh, my God.’”

That’s when Short-Colomb found going to the cafeteria uncomfortable. “They have an open floor plan where the food workers can interact with the students. I had spent twenty-plus years on the other side of the food line, so going into that atmosphere to eat is not particularly attractive to me.”

The Chef Cooks in Her Dorm Room

These days, Short-Colomb cooks most of her meals in her dorm room, a single where the bunk bed was disassembled. “It was too hard for a 65-year-old to climb so high to bed,” she says.

It’s not that she’s anti-social; Short-Colomb doesn’t want to have to eat during proscribed cafeteria hours. As a professional chef with a bootleg kitchen, complete with an Instant Pot, toaster and a full refrigerator, Short-Colomb probably eats better than most undergrads and does so whenever she feels like it.

Though there are no undergrad Georgetown students close to her age, Short-Colomb sees others who look like her there — workers behind the counter or behind the scenes, making the university function. And that makes her feel less isolated.

Short-Colomb will be 67 when she walks across the stage in her cap and gown to accept her diploma in 2021. If she knows what she plans to do with the Georgetown credential, she’s not saying.

This much she will reveal: “I’m going to leverage that degree to make life better for my family, for the world. A Georgetown degree was never on my bucket list. I’m still a work in progress."