A Candid Conversation with Dr. Tony Fauci

The focus of a new PBS documentary, the now-retired director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases talks about the stress of the COVID pandemic and how his work during the AIDS crisis profoundly affected his career

It has all the makings of a TV episode set in the nation's capital. And the storyline is true. A woman collapsed and hit her head at a fancy Washington dinner, prompting the inevitable call: "Is there a doctor in the house?"

Turns out there was. America's doctor himself, 82-year-old Tony Fauci in white tie, tended to that patient (and another woman who fainted) at the Gridiron dinner on March 11. (Both women did fine, Fauci reports.) A Washington speechwriter snapped a photo and tweeted it out.

So it goes. Just 10 weeks after retiring from a 54-year career at the National Institutes of Health and no longer the public face of the pandemic, let there be no doubt Fauci is still a physician at heart. He tells Next Avenue over the years in Washington, it hasn't been that uncommon for him to administer aid to people in distress at large gatherings. "I had to actually save someone's life who was choking by performing a Heimlich maneuver," he recalls.

"My whole professional life, every day of it, from the time I got out of medical school, has been in public service."

Few felt the full weight of the pandemic more than Fauci. As the deadly virus spread throughout the country, he kept impossible hours — not a day off in three years. And sheepishly, he concedes he was never the poster child for work/life balance, but especially the last three grueling years.

You can imagine Fauci's stress level climbing as America's COVID death toll rose and the variants kept coming, one after the other. And layered on top of that first year, Fauci was advising President Trump, who would make off-the-cuff statements about the virus that satisfied his political instincts but were not always grounded in science. So Fauci felt compelled to publicly correct misinformation the President or members of his administration shared. That put a bullseye on his back from some of Trump's followers and triggered death threats.

'The Toughest Period of the Virus'

On January 20, 2021, the first anniversary of the first American to test positive for COVID-19, a new President was inaugurated, and Mr. Biden used his speech to level with the nation that "we're entering what may be the toughest and deadliest period of the virus." While the Biden administration was more careful in what it said, it also consulted more frequently with Fauci and other public health leaders, who urged more transparency.

The Biden White House was the seventh administration Fauci has advised. And along with his all-consuming, laser-like focus on the ever-changing virus, Fauci still had his day job as the longtime Director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. But he had never been through a transition quite like the one from Trump to Biden, including the storming of the Capitol with the threats by insurrectionists to hang Vice President Pence. "What the hell is going on here?" he's filmed asking.

When the Biden Administration took over, the politics and pushback of mask mandates, school closings, social distancing and vaccinations only intensified. Today, America's COVID death toll stands above 1.1 million.

Imagine being in the center of the clash between science and the anti-vax/anti-mask/anti-government activists. Imagine being nearly three months retired from a long career in public service but still requiring 'round the clock protection. Imagine being Dr. Tony Fauci.

Now you can. On Tuesday, March 21 at 8 p.m. ET on PBS, an eye-opening, behind-the-scenes two-hour "American Masters: Dr. Tony Fauci" follows America's doctor for 23 months of the pandemic until his retirement from government at the end of 2022. (Check local listings for details.)

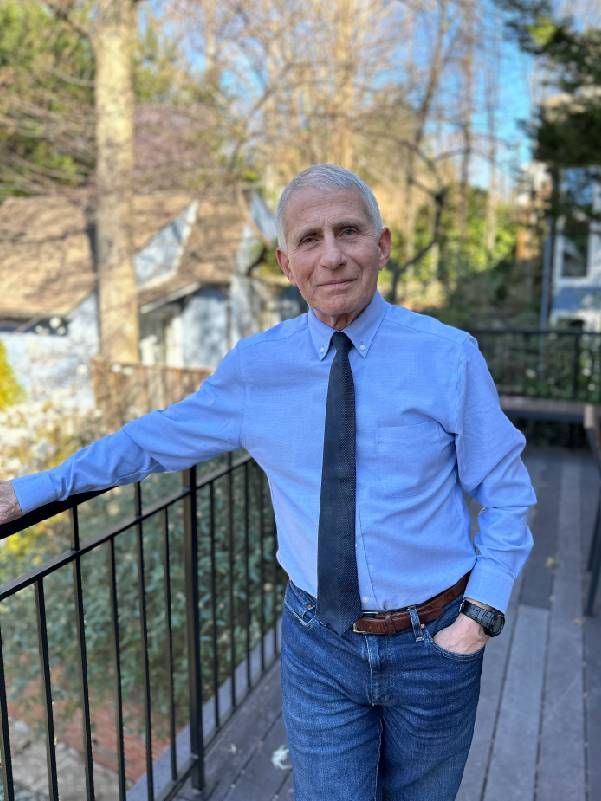

Next Avenue sat down this week with Fauci at his home in Washington, D.C.

Next Avenue: Knowing the incredible stress you were under as the public face of the pandemic, why were you willing to add yet more stress and agree to be the subject of this documentary and be tethered to a camera for a couple of years?

Dr. Tony Fauci: That has somewhat to do with one of the reasons why I decided that the time had come for me to step down from my position at the National Institutes of Health for 54 years and being the Director of the Institute for Allergy and Infectious Diseases for 38 years. My whole professional life, every day of it, from the time I got out of medical school, has been in public service. It was literally medical school, internship, residency, fellowship, chief residency, NIH. So, I asked myself, 'What can I continue to contribute in somewhat of a unique way?'

And what I feel strongly about, perhaps because of my special circumstance, is to be able to inspire younger people who are either in science or who are considering going into science and medicine and public health and perhaps a few even into public service, that if they saw an example of how exciting and impactful a career in science, medicine, public health and public service could be, that they may be encouraged to pursue that path.

"I think we clearly are doing better only because there's a degree of community protection."

So I think one of the best ways to do that would be to get a really talented group like (filmmaker) Mark Mannucci and his team and invite them to see what I do for two years. And I think that the film is going to do that. If you looked at the expression on the faces of the Cornell medical students who were in the audience last night when they showed a preview of the film, no doubt they got very excited about that. I think that's going to be my contribution instead of yet another paper or another clinical trial. And perhaps writing a memoir, where people can read it and say, 'Hey, maybe this is something that I might want to do.'

It's been two and a half months since you stepped off what must have felt like a nonstop hamster wheel inside a cage as the public face of the pandemic. With the benefit of a small break, how do you think the country is doing vis-à-vis the pandemic?

I think we clearly are doing better only because there's a degree of community protection. So if you look back a year, a year and a half ago, we were having 3000 to 4000 deaths per day. And now we're doing much, much better but still, in my mind, at a level where we shouldn't be complacent because we have 3 to 400 deaths per day. And just a few days ago we slipped up to 500 deaths in a given day. That could have been a fluke in the counting, but the average is around 400 [a day], close to 3000 deaths a week, which is in my mind, still an unacceptable level for us to say we're done with it, we're okay.

Without realizing it, perhaps, you were part of a test this month because you attended last year's Gridiron dinner, which turned into a superspreader event with dozens of people testing positive. And then you were back again this month, and I haven't heard any reports of people at that dinner testing positive. So what does that tell you?

It tells us from March of 2022 to March of 2023, more people got infected, more people got vaccinated and more people got boosted. I still don't want people to think that we have reached the ultimate optimal level of vaccination. We haven't. We still have only have 69, 70% of the population vaccinated and less than 20% of the people who are eligible for the BA.4 or BA.5 updated booster have gotten it. That's a very low number, less than 20% of the eligible people.

Regardless of whether it turns out that the origin of the COVID-19 virus was either a natural occurrence or some kind of a leak from that lab in Wuhan, China, why do you think it's essential to get to the bottom of it one way or the other?

Because you want to make sure it doesn't happen again. Instead of arguing and wasting energies by pointing fingers, what we want to do is make sure if there are two viable possibilities, we strengthen the defense against both of them.

There were many jaw-dropping moments for you and the country when President Trump offered his opinions of various therapies for COVID with seemingly no evidence to back them up. Was there one moment when your jaw dropped and stayed open?

I think it was when he said, 'I think hydroxychloroquine works and I got a good feel for it. And it's just my opinion. I got good judgment. It works.' And I said to myself, well, this is a complete rejection of the scientific process. Complete. Stark. Maybe people didn't quite get it. But what he was saying is that my gut — he has no experience in medicine and no experience in science — my gut is that it works. And I know a lot of people telling me it works when the scientific data were very clear that it doesn't. That to me was, wow, wow. Then, reinforcing that danger was when he got tired of my telling him that these things were wrong. He brought in his own set of experts, (radiologist) Scott Atlas, who would tell them exactly what they want to hear. The Great Barrington people would also tell them exactly what they want to hear (a 2020 declaration by a libertarian free-market think tank that lockdowns could be avoided, at-risk people could be kept safe, but no other steps would be taken to prevent infection and herd immunity would result.) Then I said, man, we are in trouble. Because not only is he rejecting the scientific process, he's bringing in people to fortify his rejection of the scientific process.

"Maybe there should be more programs within agencies to bring in young trainees for a period of a year or so to not only contribute to the organization, but also to learn."

You co-wrote an op-ed in The Washington Post last month that will be of special interest to our readers. It was a plea to recruit more young people into the graying federal workforce. Apparently, only 7% of the permanent full-time federal workers are under 30, compared to 20% in the broader labor market. In addition to the four steps you recommend, I'm curious how much cross-pollination there is between the experienced older federal workers and the younger workers with fresh ideas with both groups having something to offer the other?

I happened to be fortunate enough to have been for 54 years in an agency where that's the rule instead of the exception. Every year, our program, that I was responsible for, would bring in a whole cohort of people right out of their medical residencies or their PhDs. And we would train them in immunology and infectious diseases and many of them would either go off and cross-pollinate another agency or stay in the agency. And no doubt people like me who are now considered elderly and some of my contemporaries who are still there have benefited greatly from young people coming in and asking questions that you probably wouldn't ask because you would think that they were too off base. And yet they turn out to be very creative. On the other hand, they benefit greatly from our experience. Now, not every agency is structured that way. Maybe there should be more programs within agencies to bring in young trainees for a period of a year or so to not only contribute to the organization, but also to learn.

One of the things I noticed early in the film is your ability to inject some humor in what was a very dark time. As the new COVID variants kept coming, you said "the only thing I could think of" was Gilda Radner's character on Saturday Night Live, Roseanne Roseannadanna who famously said, "If it ain't one thing, it's another." How important was humor to get through this incredibly bleak period with hospitals overwhelmed, body bags stacked up and people whose loved ones died alone with families not allowed at the hospital bedside?

I think humor is absolutely critical to be able to get through what we got through. I still, in some respects, have what I refer to, not too melodramatically, but I think realistically, a degree of post-traumatic stress syndrome from my years caring for HIV/AIDS patients. I was personally daily — multiple hours a day — taking care of young, previously otherwise healthy, almost all gay men. You really develop a relationship with them when they're your patients, seeing them week after week, month after month, year after year, all dying is very, very tough to incorporate into your general being without somehow having a release. So, I think I inherited a really good sense of humor from my father. And sometimes you just got to use humor to relieve the stress.

You mentioned AIDS and I believe the first time we met, about 36 years ago, was when I invited you to the AIDS town meeting on "Nightline." You've had a career that's been basically bookended by AIDS and COVID-19. And one thing you said in the film is how the early days of AIDS were traumatic for you. You went from a world of success and gratification to a world of frustration and failure.

It was stark and abrupt because I was very fortunate as a young investigator to get involved in a study of a group of diseases that were not very common, but common enough — there were hundreds, if not thousands of people, that had it as opposed to hundreds of thousands and millions. But the disease was almost uniformly fatal. And one of my first projects was a combination of having a great mentor, a little bit of luck and some talent on my part and guts because it took guts to take the chance of using otherwise highly toxic cancer drugs at a low, low dose that wouldn't harm the patient but would suppress the aberrant immune response. And it took us over a period of a year, and then we studied it for an additional ten years, we took a group of diseases that had like a 95% mortality, and we brought it down to a 93% remission. So at a young age, I was like 29, 30, 31. All of a sudden, I, along with my mentor, became very well known for transforming a particular disease.

So, from 1969, when I started on it, up until 1981 was almost a full decade of total success. People come in with a disease they heard is going to kill them, and [said] 'Tony Fauci saved me.' So it was families, we love you and all that. It was almost unbridled success.

"I still, in some respects, have what I refer to, not too melodramatically, but I think realistically, a degree of post-traumatic stress syndrome from my years caring for HIV/AIDS patients."

Then all of a sudden, I decided, based on what I felt was the challenge of this unusual disease, which fascinated me because it was brand new, to go back in the history books. When is there a brand new disease? This one was deadly, and it was an infection. And I was a trained infectious disease guy and it destroyed the immune system. And I'm a trained immunologist. So I said I'm going to devote all of my time to this. But then the reality of it set in and the reality is the trauma, because we were admitting these young gay men. We didn't know what the virus was. It felt like you were swimming in the dark, in a very ominous river. And we kept on admitting these young gay men. And then it became clear that one after the other, they came in, they got a horrible death. And then it was becoming clear that this was a totally traumatic situation where it was like white and black going from total success to complete frustration and failure.

You described it in the documentary as feeling impotent.

We were putting Band-Aids on hemorrhages, and I think that was the incentive that made us work so hard to get the virus, understand the virus, and develop effective therapies. And we were successful because we went from everybody dying to the triple combination of drugs that now, not all, but 99% of them survive and lead relatively normal lives.

You've compared having the early AIDS activists, like Larry Kramer, put a bullseye on your back with the current pandemic activists putting a bullseye on your back, saying they are a thousand percent different. How so?

The bullseye on the back with HIV/AIDS was that the activists, those who were living with HIV and at risk for HIV, fully realized that the scientific structure and regulatory process were ill suited to the uniqueness of what they were experiencing. It was an almost uniformly fatal disease that by the time you realized that you were infected, your life expectancy was very low. The only hope you had was to be on a clinical trial, and the clinical trials were extremely rigidly restricted, and the regulatory process was drawn out, geared towards making sure we had safe and effective drugs under a period of time that maybe worked for many diseases in which you had alternative therapies. But when you had a disease where you didn't have any therapies and the only approach of a patient to get any kind of relief would be in a clinical trial and you needed something to be available quickly, what the activists were saying was, 'You guys are sticking to these rigid ways. You've got to listen to us. You've got to pay attention.'

I, as well as the scientific and regulatory community, took the stance that we are the scientists, you are the constituents. We know better and didn't pay attention to them. And when we didn't pay attention to them, they made a decision. We have to be theatrical, confrontational, iconoclastic and disruptive. Then maybe you'll listen to us. They figured they couldn't just yell at a vacuum. So they said, 'FAUCI! He's the guy that's on TV. He's the guy that's talking about HIV.' Even though what I was doing was geared at saving their lives. Didn't matter. 'You're the boss, you're the head of NIAID. You're the one we're going to come after.'

"But one of the things that I can do is that I have a great deal of tolerance and empathy for even people who are attacking me."

You say in the documentary the AIDS activists were trying to get you to see what the truth was for them.

So that is totally different than the group of people today who are driven by untruths, distortions and conspiracy theories and in a politically motivated way, want to demonize you. There's no message there. It's pure demonization. The message of the AIDS activists was, 'please listen to us. We have something to say.' The people who are trying to kill me now [because of their views on COVID] where I have to have security with me, their message is we want to take you down.

Ironically, one of the early AIDS activists, Peter Staley, who made peace with you over the years, wrote a lovely New York Times piece upon your retirement from NIH saying because you crossed President Trump, you turned into a villain for the MAGA crowd. He wrote, "There has rarely been a larger gap between a mob's viciousness and its target's decency."

That was an amazing line.

The culture wars have seemed to infect every part of our country. You know it first-hand. Your former boss, Francis Collins, who preceded you by a year in retirement from NIH as its director, is trying to build bridges and bring people together. How have you thought about trying to address the problem in this new chapter for you, what your wife calls your rewiring?

Well, Francis is a born-again Christian who is very serious about his faith. And he is particularly troubled that his people, evangelists, are the ones that are very much far right, doing some of the things that are very disturbing, distortions of the truth. So he wants to use his credibility in that arena to try and reach out to people and say, 'What are you doing? Why are you distorting things and why are you believing things that are patently untrue?' I think he's very well positioned to do that.

That's not my bag, because I'm not of the faith-based community. But one of the things that I can do is that I have a great deal of tolerance and empathy for even people who are attacking me. I've always had that dating back to my reaching out to the AIDS activists. So I would love to be able to reason with and speak to some of the people who are willing because I don't think everybody is Marjorie Taylor Greene. A lot of these people just somehow got sucked into believing things that have no foundation in reality. I think there's a pathway there to reason with people by writing, by lecturing, by interacting in groups. I would be perfectly willing to expend some energy in doing that. I just have to find the right setting.

You have spent your professional life trying to improve public health. Indeed, among your legacies is developing the President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief — PEPFAR—with President George W. Bush that has saved 25 million lives in developing countries in Africa. But now we see in the Washington Post that in the wake of the pandemic, a spate of state laws has passed in 30 states since 2020 limiting public health authority. Thinking ahead to the next pandemic, won't that put one hand behind the back of your successor, the head of the Centers for Disease Control and other public health leaders?

I think that's going to be very, very potentially dangerous when you essentially take away all authority from health officials and essentially make regulations and restrictions — or not — on the basis of a political ideology that can really hinder an adequate public health response. So that's very troublesome if that's the case. It's a pure overreaction, I think.

I want to close by returning to the opening montage of the documentary. You say something that goes by very quickly, but it's rather chilling, and stayed with me since I watched the film. You said, "I worry less about the future related to COVID-19 than I do the fate of our country." What's your fear?

What I fear — and I'm not a political scientist or a social scientist — I got a good feel for things, I think. I'm worrying about the integrity of our democracy. I think our democracy is at risk. I think January 6 was, to me, one of the most disturbing and frightening things I have ever seen in my entire life. Not only that it happened, but that so many people denied that it meant anything. I mean, that people could actually say this was just a harmless social event. That's the thing that's particularly disturbing to me when you look at the footage with your own eyes.

I don't want to get too melodramatic, but one of the things I've seen in the few hobbies I had before I became a workaholic was history. And you read the history of Europe in Germany in 1930s, leading up to World War Two. That's exactly what happened. It was a complete distortion of reality that had otherwise good people do horrible things. So I'm sorry, but that's what worries me.