Vietnam: 'Because Our Fathers Lied'

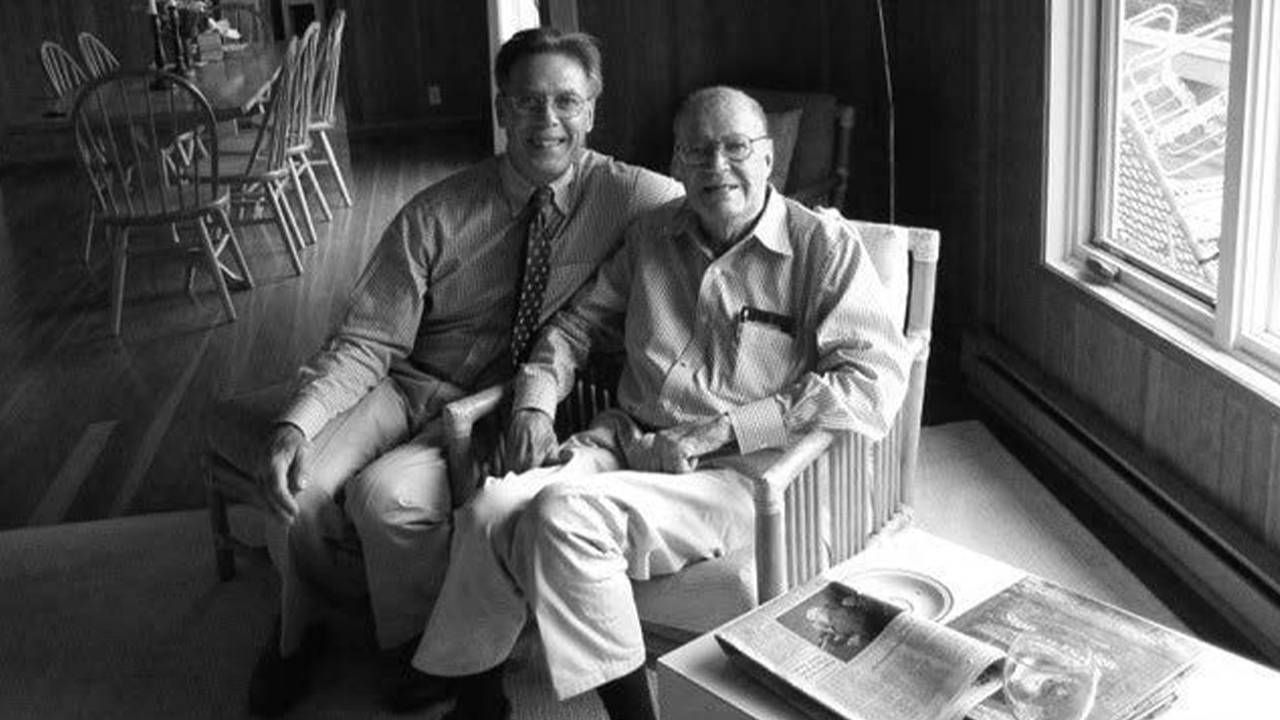

Craig McNamara remembers his famous, vilified father, a former Secretary of Defense

The war in Vietnam was a contentious issue in many households in the 1960s. Opinions were rarely neutral and often emotional. The era was especially difficult in the McNamara family. Craig was adamantly anti-war. His father, Robert, was Secretary of Defense and widely known as the architect of the war.

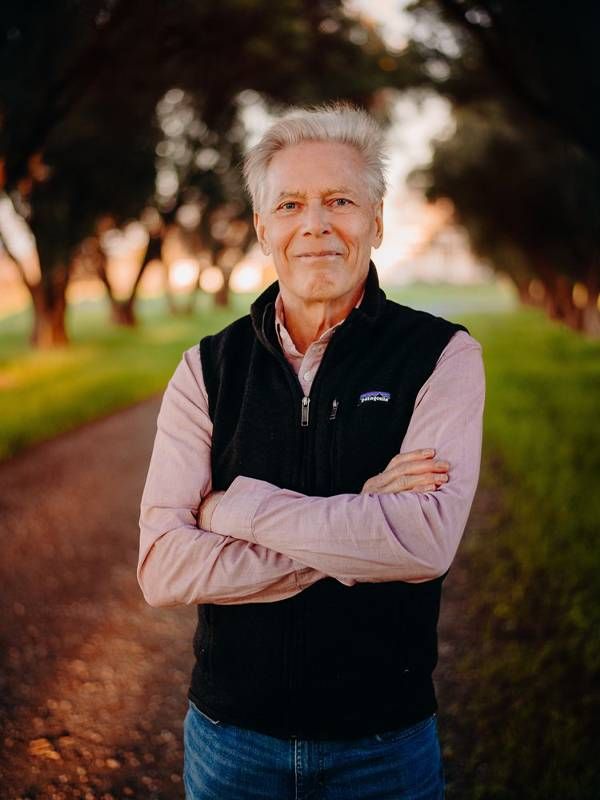

When Craig McNamara talks of the Vietnam era, he is as likely to quote historical facts or literature as he is to reveal his opinions. He is respectful of everyone he mentions. McNamara's memoir, "Because Our Fathers Lied," is a thoughtful reflection of his relationship with his father.

"It's a love story," he says, "with the challenges that all relationships have."

"From that point forward, I engaged in a tremendous amount of resistance to the war."

McNamara first became aware of his disagreement with his father when friends organized a teach-in at his high school. It was 1965, during escalation of the war, and Craig was 15 years old. He decided to balance the conversation by presenting his father's perspective at the event.

A Personal Turning Point

"I remember being in a phone booth calling my father from the school, saying, 'Dad, if you have any information that supports our involvement in the war, please send it to me,'" McNamara recalled. "To the best of my recollection, nothing ever arrived in my mailbox."

"That teach-in was very important in my understanding of why the war was an unjust war," he added. "From that point forward, I engaged in a tremendous amount of resistance to the war."

That was the beginning of the decades-long gap between father and son. McNamara says his father avoided discussion of the war.

"My father and I, on the exterior, didn't have a confrontation," he said, "and that's because we followed his pattern."

As a university student in California, Craig McNamara became active in anti-war protests in San Francisco and Berkeley. Before he finished his studies at Stanford, he felt the conflict in his family as keenly as the nation felt at odds. He and a couple of friends dropped out of school and rode their motorcycles to South America.

"It was such a tumultuous time in our nation's history. I was so disenfranchised from our country at the age of 21," McNamara said. "I knew I loved our country, but I lost that love. I lost that connectivity. I needed a new perspective, and the only thing I thought I could do was to leave it in search for it."

McNamara stayed in South America for a couple of years and had minimal contact with his family. His father also experienced a major transition, having left his position as Secretary of Defense to become President of the World Bank.

The War Ends, the Schism Remains

The war ended in 1975 with the Communists victorious, but the relationship between the McNamaras was still strained. Father and son shared a love of nature and sports, but they could never broach the topic of Vietnam.

"Within families, the stories need to be told when they're age appropriate," Craig McNamara said. "So maybe as a 15- or 16-year-old, as you, the Secretary of Defense, are continuing the war, sending more and more troops, doing much more bombing, dropping napalm and using Agent Orange, maybe that is not the appropriate time to share your concerns with your son.

"But as a 21-year-old, a 31-year-old, a 41-year-old, a 51-year-old, a 61-year-old, those are the times that a father and son need to break down those barriers and share what you hold. Because the war was a tragedy, not just for the 58,000 men and women — our U.S. soldiers — who were killed, but for the two to three million Vietnamese and Laotians who were killed. That's a tragedy for all involved. I think it was incumbent upon my father to engage in dialogue with me. And that never happened."

McNamara carefully chose the title of his memoir. The line, from a Rudyard Kipling poem, exemplifies a father's grief over a lie. Kipling used his influence to help his son enlist in World War I despite a medical deferment. His son died in combat.

"It's the sorrow that Rudyard felt over the lie he told on behalf of his son," McNamara said. "People have asked me why I used 'Because Our Fathers Lied.' I used it because it was a direct quote from Rudyard Kipling, and I used it because our fathers do lie. It wasn't just my father who lied."

Craig McNamara is not sure whether his father grieved the losses in Vietnam, or whether he found healing through writing his memoir, "In Retrospect," published in 1995.

A Missed Opportunity to Heal

"That's a tragic loss because he took Vietnam to his grave," he said, "and I think he could have found some solace in moving beyond apology."

In filmmaker Errol Morris's 2003 documentary "The Fog of War," Robert McNamara admitted he was wrong in his directives in Vietnam. His son says that apology was not enough.

"He needed to go much farther than an apology or 'I was wrong,'" he said. "Those are the initial steps a person needs to take when you've caused such tragedy as was caused under his tenure as Secretary of Defense. What I wanted him to do was to apologize to the families, to the veterans who had come home damaged and injured, to the families who suffered loss."

"I wanted him to do something formidable for those families, to ensure that every veteran in wars to come would have the resources to help them to become well," McNamara added. "I wanted him to ameliorate the situation of the napalm and the Agent Orange. Pay forward for the damage that was done backwards."

The communication gap continued until the elder McNamara's death in 2009. It was then that the son seriously considered writing his own memoir.

"He needed to go much farther than an apology or 'I was wrong.'"

"What I think about is if he were here in this room today, if he had read my memoir, what would he feel?" McNamara said. "How would he respond? Would he be tremendously saddened? Would he feel that I'd betrayed him? I don't think he would. And I don't think I'm fooling myself on this."

"Could I have written it while he was alive?" he added. "It probably would have been more difficult. It's that many years later, and I'm that much more down the road."

Craig McNamara's life has taken a path that attempts healing from the pain his father generated for so many people. He serves on the board of Project Renew, an organization in Vietnam that that provides services for victims of unexploded munitions from the war.

As a walnut farmer in California's Central Valley, his focus is on regenerative agriculture, leadership and teaching the next generation of farmers.

His legacy, he says, is integrity. And to be an honest father.