What It's Like to Participate in a Vaccine Trial

The author, part of a trial for a new Lyme vaccine, learned patience is a requirement

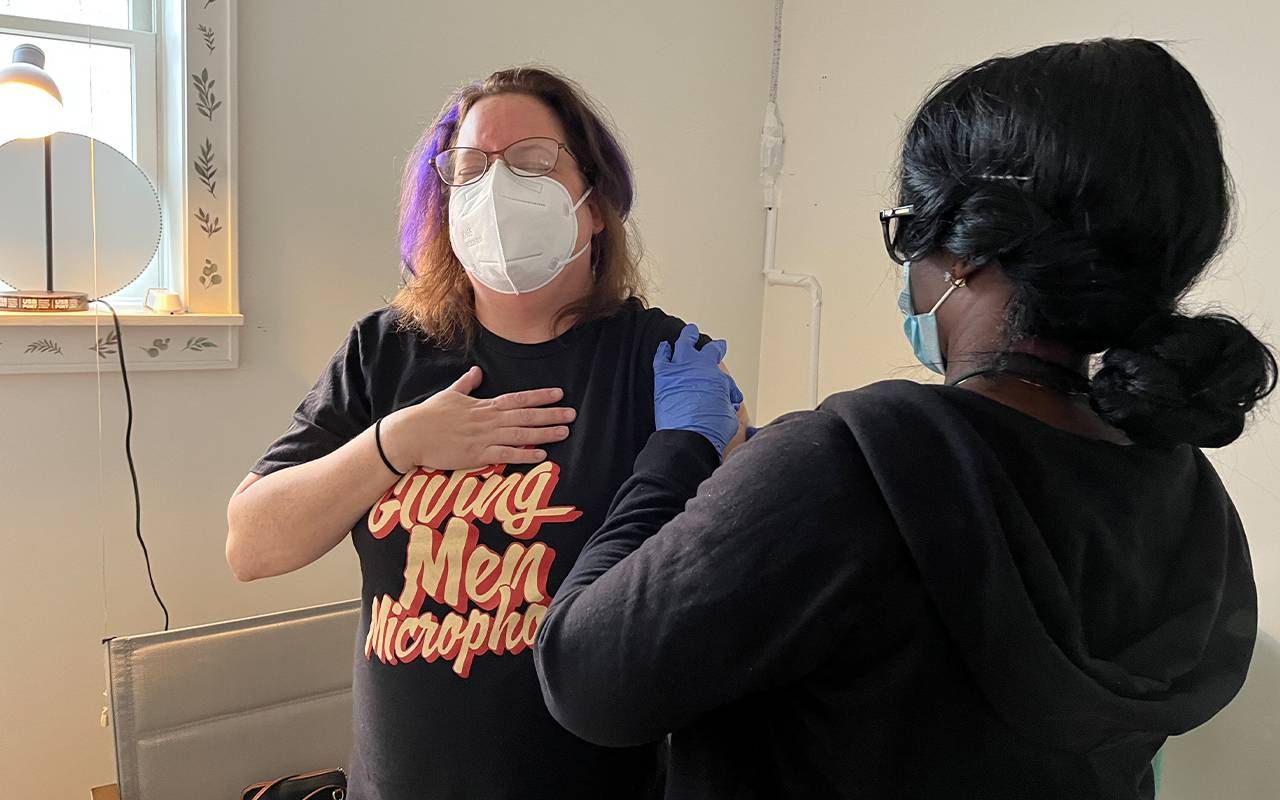

Alisa Costa sat in a folding chair, holding a white plastic kitchen timer set to 30 minutes indicating she could go home. But she wasn't bored; she was excited. The 48-year-old consultant had just received her second injection as part of Phase 3 clinical trial for a new Lyme vaccine from pharmaceutical giant Pfizer and its French biotech partner Valneva.

"I've suffered from Lyme disease in the past, so I do not want to go through that again," explained Costa, "And it's an issue for a lot of my friends who have long-term Lyme disease."

So she couldn't wait to make the 90-minute drive from Pittsfield, Massachusetts to the temporary clinic in Brattleboro, Vermont. "I don't want to see other people suffer, so being a part of making sure that other people can stay healthy is really exciting for me."

Lyme is a particular threat to older people as one of the lingering symptoms of untreated Lyme is arthritis.

I was there because I, too, was a participant in the same trial. As with Costa, my journey started with a recruiting ad on Facebook. It got my immediate attention as I live on a woodsy plot in New York's northern Catskill region, close to Ground Zero for Lyme disease, named for the origin of its discovery in Lyme, Connecticut.

I'd had a mild bout with Lyme the previous summer, and I know that Lyme and other tick-borne illnesses are a growing threat in the U.S., driven by expanding tick populations and climate change. Lyme is a particular threat to older people as one of the lingering symptoms of untreated Lyme is arthritis. So while scrolling Facebook, it was like Pfizer was reading my mind.

No Guarantees

I went into it with my eyes open. But, as with most clinical trials, there were no guarantees. There was only a 50-50 chance that I'd be getting the vaccine — half the participants would get a saline placebo — and if I did, there was no guarantee it would work. That's why they call them "trials." But efficacy is the second consideration in any vaccine trial.

If patience is required from the study team, more is demanded from the subjects.

"Safety is obviously paramount in everyone's mind," says Alan Rothman, an infectious disease physician and immunologist at the University of Rhode Island. Some years ago, Rothman participated in clinical studies for an early candidate vaccine for HIV.

"You initially start out with a small number of individuals to make sure there isn't some surprising common severe side effect, and to get a sense of how well people tolerate the vaccine," he says.

By the time they got around to me and the other Phase 3 subjects, Pfizer had already tested the Lyme vaccine on about 1,200 people.

The further they progress with satisfactory results, the more people get involved. "You want enough people in your study to get sufficient safety data," explains Rothman. That's why the first two phases of a typical trial focus on safety.

Of course, the other big question is how well the vaccine does its job. "By definition, a vaccine is a product that has its desired effect through induction of an immune response," explains Rothman.

"Phase 2 is a larger subset of people that tends to focus still on safety, but might start to get information about whether the vaccine's effective," he continues. "By Phase 2, if not by Phase 1, you're also studying the immune response to the vaccine."

Diversifying the Vaccine Studies

Drugmakers have been pressured to build more racial and ethnic diversity into their studies, so pharmaceutical companies recruit aggressively. Pfizer wanted 18,000 subjects for this trial. That sounds like many people, but with half getting a placebo, that leaves 9,000 subjects with which to study the effectiveness.

Drugmakers have been pressured to build more racial and ethnic diversity into their studies, so pharmaceutical companies recruit aggressively.

The vetting process is meticulous, and not all applicants are accepted. Mine began with a screening phone call and a 21-page consent form that disclosed every aspect of the study, including the risks, then moved through a series of visits to the clinic with interviews, in-depth medical histories, blood samples, and finally, injections of the experimental vaccine.

I was sent home from my first visit with a digital thermometer and a plastic caliper to measure any rashes that might break out at the injection site. I used neither, as I did not react to the "jab." Oddly perhaps, that was a bit disappointing as it made me suspect I only got the placebo.

On the other hand, Costa was convinced by the rash on her arm that she got the real deal. All of it was sheer speculation mixed with a bit of wishful thinking, as the study staff would not let on which one we got — revealing who got what would invalidate the study results.

Patients and Patience Both Required

There's no such thing as a speedy trial, and that's a good thing. But it can be frustrating for study subjects – like me – eager to see a commercial vaccine become available. The Pfizer disclosures said it would take more than two years to gather the necessary data to apply for the Federal Drug Administration's approval of this "investigational" Lyme vaccine.

Nevertheless, the success of Pfizer/Valneva's VLA15 vaccine would mean protection against the rapidly-growing Lyme threat could be available for the first time since a rival vaccine was dropped in 2002 due to lackluster sales. (Though not technically a vaccine, MassBioLogics is testing a fast-acting Lyme shot, shooting for approval next year.)

The relative fast-tracking of a COVID-19 vaccine was highly unusual, authorized only in response to a deadly global pandemic claiming millions of lives. And in the case of all new vaccines, including those for COVID, questions of efficacy can linger.

"The challenge from a vaccine standpoint is…we don't know starting out, how long the vaccine will work," says Rothman. "The vaccine might work really well in the first year, and it might not work as well in the second year. So you're trying to keep the time frame of the study sufficiently confined that you're gonna test what you want to test."

If patience is required from the study team, more is demanded from the subjects. I would not find out until at least the end of the study, if ever, whether I got four shots of the vaccine or four shots of saltwater.

Epilogue

Sadly, my trial was cut short. Pfizer had a dispute with Care Access, the subcontractor hired to run the Brattleboro clinic, over handling of the study data. My data and that of about 2,000 other participants was discarded from the trial. So I may never know if my two injections were the vaccine or salt water.

It was a huge disappointment – especially after the time and miles I'd already invested – but I take it on faith that Pfizer made the move out of an abundance of caution, wanting the best possible outcome with the highest confidence in both the safety and efficacy of the product, if and when it eventually makes it to market.

"We forget how much that we all rely on people to volunteer and participate in those things."

I'm rooting hard for it to work. Pfizer says it is so far "encouraged by the data" it has retained from the trials and is still planning to file for FDA licensing of the vaccine sometime in 2025.

Alisa Costa says she wasn't discouraged by the abrupt end to her trial. "I would do it again," she says without hesitation. "I think this research type is essential, and vaccines are safe." That kind of confidence is increasingly crucial when vaccines of all types are coming under growing suspicion.

Moreover, having willing subjects for clinical trials is critical to advancing medicine. "We forget how much that we all – the rest of us – rely on people to volunteer and participate in those things," says Rothman.

"I'd feel very confident going to another trial if I ever had that opportunity," adds Costa. Meanwhile, all she can do is hope that the two shots she got were real and gave her at least some protection against Lyme.

Getting ready for bed on a recent Saturday, she looked down to see a tick crawling across her foot.

Editor’s note: Care Access would not comment on this story, and queries to Pfizer media relations were met with no response.

Read More