OPINION: When A Stroke is On the Ballot

A stroke survivor calls out those who would use John Fetterman’s debate performance to disqualify him from the US Senate

With the midterm elections just days away, this is not another story about our broken politics, nor who is most likely to become the next Senator from the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania.

Instead, this is a story about disability, bravery and determination.

It's been five months since Pennsylvania's Lieutenant Governor John Fetterman, the unconventional six-foot-eight, hoodie-wearing, tattooed Democratic candidate for the US Senate, suffered a serious stroke that nearly killed him. He was forced to stay off the campaign trail until recently. And though he was still in the throes of his recovery, Fetterman agreed to take the stage for just one encounter with his opponent — Republican Dr. Mehmet Oz — a debate like none we've seen before.

Fetterman used his opening remarks to address what he called "the elephant in the room"

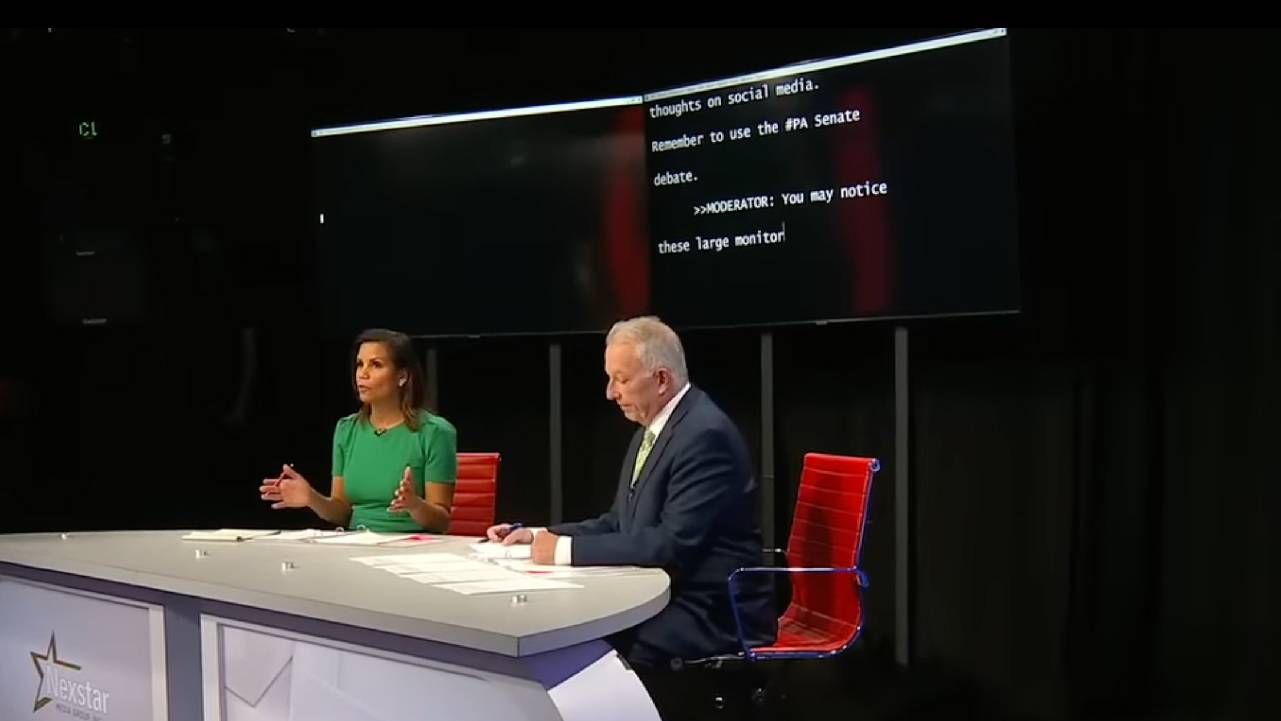

For starters, two 70-inch monitors hung above the moderators, scrolling the closed-captioned text of their questions in real time, along with transcribing the candidates' answers in the second screen. The accommodation, agreed to by both sides, allowed Fetterman to read the questions and not rely on the voice of the moderators.

Just three minutes in, Fetterman used his opening remarks to address what he called "the elephant in the room," preparing the audience for what was to come: "I had a stroke. He [Oz] never let me forget that. And I might miss some words during this debate. Two words together. But it knocked me down. But I'm going to keep coming back up."

A Peek Behind the Curtain of Stroke Recovery

As Fetterman struggled during the hour-long sparring match to string words together, missed others and paused awkwardly at times, it was not easy to watch. But I did so not as a Pennsylvania voter (I'm not), not as a political reporter analyzing who won or lost the debate (not my portfolio), but as one of the nearly 7 million stroke survivors in the country.

For all the talk of whether Fetterman should have agreed to this debate, given that he was still climbing back from the effects of a stroke, there's been precious little talk about the courage it took for someone to let the world in on something rarely seen — a high-stakes, very public peek behind the curtain of stroke recovery.

As I watched, I couldn't help but wonder if I'd have had the guts to allow my own post-stroke speech and physical therapy to be televised live. Learning to walk, talk and swallow again following a serious stroke at my desk at "Nightline" in 2000 was a humbling experience, to say the least.

But I wasn't running for office and didn't face the excruciating choice Fetterman did — forego debates and risk the voters' wrath or let the world see what a stroke recovery looks and sounds like. Philadelphia's former Democratic Mayor Ed Rendell summed up the dilemma for a candidate still in the grip of a health challenge: "If he hadn't done this [debate], then people would say he's hiding and [not] being transparent — damned if you do, damned if you don't."

The Medical Report and Auditory Processing Disorder

It was just days before the debate that Fetterman's primary care physician, Dr. Clifford Chen, issued a medical report on his patient: "His physical exam was normal … he spoke intelligently without cognitive deficits. His speech was normal and he continues to exhibit symptoms of an auditory processing which can come across as a hearing difficulty. Occasional words he will "miss" which seems like he didn't hear the word but it is not processed properly…. he has no work restrictions and can work full duty in public office."

Many who watched Fetterman on the debate stage may have wondered if the "auditory processing disorder" Chen described suggested any cognitive impairment. So I turned to Dr. Rhonda Friedman, who as a PhD, directs the Center for Aphasia Research and Rehabilitation at Georgetown Medical Center in Washington.

She said, "As words come in, the sounds are heard but they are not readily identified as the words that they are supposed to be identified as. The word 'cat' comes in and might be heard as 'gat,' so you don't know what it is because there's no word 'gat.'"

But Friedman says a leap from an auditory processing problem to a cognitive one is one people shouldn't make. "It really made me mad to hear a person after the debate say 'based on what his [Fettterman's] performance was I don't think he could do this job.' It really upsets me to think if you're not perfectly processing sounds then therefore you can't think and do your job. That's offensive to me. Would you say that someone who's deaf could never hold that kind of office? That would be pretty outrageous."

Having gone through my own stroke therapy, I was able to watch the Fetterman-Oz debate with a knowing, empathetic set of eyes.

At a rally following his debate, Fetterman again addressed the elephant in the room: "To be honest, doing that debate wasn't exactly easy. Knew it wasn't going to be easy after having a stroke, after five months. It's never been done before in American political history actually."

Six years ago, another Senate candidate, Mark Kirk, an incumbent Republican in Illinois, was dogged by questions of his fitness for office following a serious stroke. That prompted me to write a Next Avenue essay questioning whether a Chicago Tribune editorial should have used Kirk's stroke as the main reason for not endorsing him. It was especially odd because Kirk's opponent Tammy Duckworth also has to overcome physical challenges, having lost two legs in the Iraq War and has been confined to a wheelchair. Duckworth got the Tribune endorsement and went on to win the seat.

No Two Strokes Are Alike

Just as I questioned the Chicago Tribune editorial's comments about the Republican candidate's stroke, I question whether Pennsylvania's outgoing Republican Senator Pat Toomey should have come out of last week's Fetterman-Oz debate with this statement on Twitter about Democrat Fetterman: "Anyone watching today could tell there was only one person on that [debate] stage who can represent Pennsylvania in the U.S. Senate: @Dr.Oz. It's sad to see John Fetterman struggling so much. He should take more time to allow himself to fully recover."

Policy differences are of course, fair game. But should any political candidate in the midst of stroke recovery whose doctor says he can "work full duty in public office" be so callously dismissed by the retiring Senator whose job Fetterman seeks?

Having gone through my own stroke therapy, I was able to watch the Fetterman-Oz debate with a knowing, empathetic set of eyes. No two strokes are alike. Different parts of the brain can be hit by a blood clot, resulting in a variety of deficits. And it's impossible to know how those deficits will recede over time.

When you vote, choose the candidate whose ideas make the most sense to you. Don't disqualify someone — Democrat or Republican — simply because of their physical challenges, disabilities or the fear that the job could be too taxing for them. Don't count them out.

Stroke is the fifth leading cause of death in the United States. That's an improvement since my stroke in 2000 when it was the third leading killer.

Stroke is the fifth leading cause of death in the United States. That's an improvement since my stroke in 2000 when it was the third leading killer. And as with so many health issues, education is key. I learned that 20 years ago when my boss at the time, Ted Koppel, urged me to tell my stroke story on a special edition of "Nightline." I was hesitant, but he convinced me I could help many people. I mentioned on the broadcast that unlike a heart attack, stroke is rarely painful, but if you experience numbness or weakness on one side of the body or lose vision in one eye, don't wait to seek help. Miracle clot-busting drugs are available but they only work if you get to the hospital within three hours of the first symptoms.

In the days after the program aired, we began getting emails from viewers who said a variation of "I recognized the signs of stroke in my loved one and got him or her to the hospital and you helped save their life." Whether I did or not, it underscores both the need for the public to better understand stroke symptoms and to not pigeon-hole stroke survivors, whether politicians or not, as somehow "less than whole," incapable of taking on difficult challenges.

I was fortunate, if you can ever use such a word to describe an ischemic stroke at age 46 that revealed a birth defect — two vertebral arteries that ran up one side of my neck with the weaker one dissecting and throwing off a clot (typically there's only one vertebral artery on each side of the neck).

For 22 years now. the lasting impact of the stroke has been negligible. A slight loss of feeling on my left side actually makes it easier to ask the person administering my COVID booster or flu shot to do so on the left side.

If you look hard enough, there's a silver lining to every stroke survivor's saga.