1966: When the Cry of 'Black Power!' Was Heard Throughout the Land

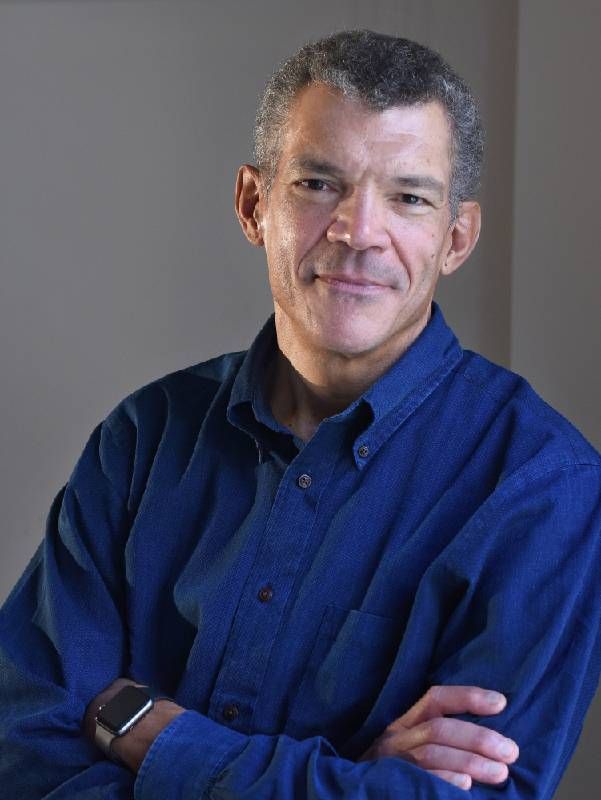

Mark Whitaker, the first African American editor of Newsweek, and a student of civil rights since age 10, revisits this pivotal year in his new book

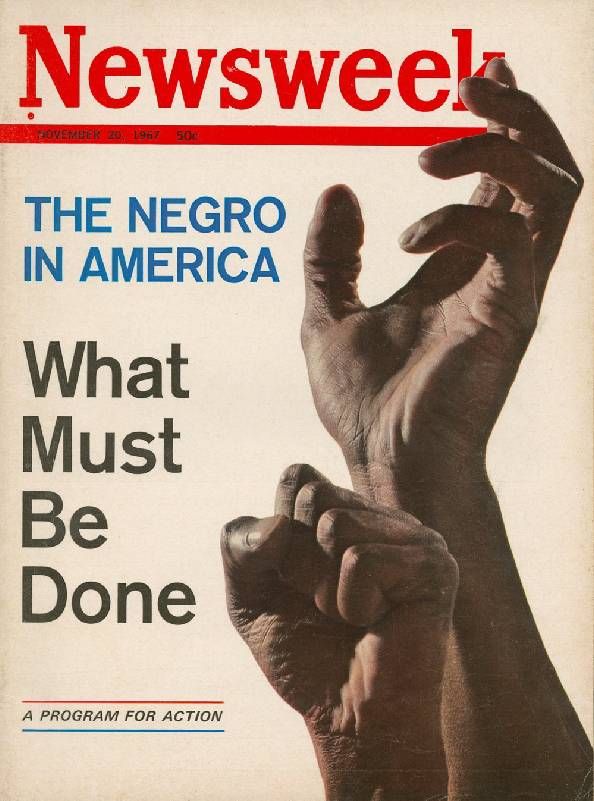

In November 1967, Newsweek Magazine did something it had never done before — advocated a position with its cover story "The Negro in America: What Must Be Done." It got a lot of attention and won Newsweek its first National Magazine Award.

It also made quite an impression on a ten-year-old biracial boy named Mark Whitaker, whose father, a Black scholar, had divorced his white mother four years earlier.

And just a few months before Newsweek published this groundbreaking story, Whitaker's father paid a rare visit to Mark and his brother. During their brief time together, Mark's father was reading Newsweek and told his son, "They do a good job on civil rights." That's all Whitaker needed to hear, and he asked for a subscription for his birthday. And as he recalled in a 2012 essay in Newsweek, "I started devouring the magazine and in its pages, I learned the details of [Martin Luther] King's murder and followed the rise of the Black Panthers."

Fast forward a decade. Whitaker was now writing for his college newspaper, The Harvard Crimson, and was offered a summer internship at Newsweek. Two successful summer stints later, an African American editor at the magazine, John Dotson, told Whitaker he might become a section head someday if he accepted a full-time job. "What about editor?" Whitaker asked. "Newsweek isn't ready for a Black editor," Dotson replied soberly, Whitaker recalls.

"That he thought it was a great publication was good enough for me, so I got a subscription and began reading about the civil rights and anti-war movements."

He did accept the job. And twenty years later, when Whitaker became the first African American to sit atop the masthead of one of the nation's major newsweeklies, he didn't let Dotson forget his comment. Newsweek was finally ready.

As editor, Whitaker continued Newsweek's tradition of digging into the enduring issue of race in America. Whitaker would later become Washington bureau chief for NBC News and managing editor of CNN.

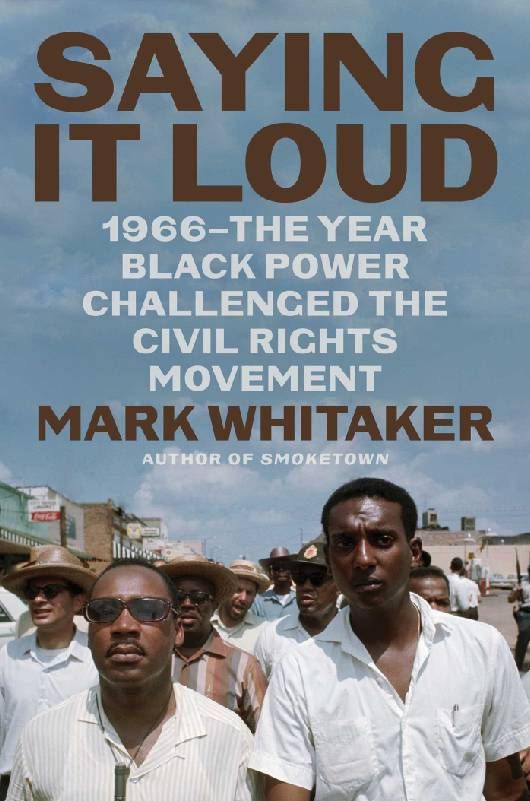

This week, Whitaker returns to race during Black History Month with his latest book, "Saying It Loud: 1966 - The Year Black Power Challenged the Civil Rights Movement." He talked with Next Avenue from New York.

Next Avenue: You must have been a precocious kid. How many ten-year-olds ask their parents for a subscription to a newsmagazine for their birthday?

Mark Whitaker: When my parents got divorced, I was six. My mother hated Los Angeles, so she made a condition of the divorce that my father allow her to take me and my brother back to the East Coast. My mother subscribed to the Boston Globe and when I was eight, started to read their sports pages and got interested in writing.

And at that point, my father had dropped out of our lives for a few years and stopped paying child support. But then he resurfaced in the summer of 1967, got in touch and said he'd like to pick us up so we could spend time with him on Cape Cod. That was when I saw him reading Newsweek. That he thought it was a great publication was good enough for me, so I got a subscription and began reading about the civil rights and anti-war movements.

There was no shortage of big news events to follow in the 60's. What stood out to you?

We had a little black and white TV. And I remember vividly my mother coming in and telling me that Dr. King was killed and turning on the TV that night and watching the coverage for what seemed like the entire rest of the spring and summer of 1968. My mother was a big Bobby Kennedy supporter and after he was killed, we watched the entire train ride when they brought his body back from California. People were lining up along the railway, crying. And then, of course, the 1968 Democratic Convention in Chicago. So that's how I really got interested in news at a pretty young age.

As you began reading more about race and civil rights, were you searching for a better fix on your own identity as a biracial kid?

No question. It's interesting. We've had so many prominent people now who are biracial, obviously President Obama, a lot of people in the entertainment world, rappers and athletes. But my brother and I knew almost nobody who was biracial. Norton, Massachusetts was a very, very white community, although interestingly, the principal of our elementary school was a very light skinned Black man and I always felt he kind of looked after me. He would wink at me in the hallways and ask how I was doing.

After my parents' divorce, my mother stayed very close to my father's family, and she made a point of taking my brother and me to visit them in Pittsburgh. And that was really an all-Black world. That's how I kept in touch with my Black identity and Black culture.

But by 1969, my father moves back East, got a job as the first head of what they then called Afro-American Studies at Princeton and he's sort of back in our lives. All of a sudden, my dad had grown an Afro, wore a dashiki and taught me the Black power handshake. I hadn't seen my father for five years, so of course he's going to make a huge impression on me. And I don't think it's too psychoanalytical to say that played a big role in my fascination with that particular period.

Those of us boomers who grew up in the turbulent sixties — and I'm just a few years older than you — think of key years in the decade: 1963, the March on Washington — marking its 60th anniversary this summer — 1964, the Civil Rights Act; 1965, the Voting Rights Act and 1968, the MLK assassination. Why did you zero in on 1966 and the rise of the Black Power movement in this book?

Here's the honest answer about 1966. Once I decided I wanted to write about the Black Power generation and once I got a deal from Simon & Schuster, I started doing research. Stokely Carmichael had first popularized the slogan "Black Power" in the summer of 1966, so I knew what my starting point would be. I thought I'd take this all the way to the end of the Angela Davis trial in 1972. But after a year of research, I was still in 1966 and wondering how am I going to get my arms around this and get this all in one book?

My editor suggested I look at historian Barbara Tuchman's "The Guns of August," where she tells the story of World War I through the first month of the war. I didn't realize how much had happened in 1966, not just on the racial front. It actually turned out to be a pivotal year in American politics. And a lot of that was in reaction to what was happening with Black Power and with the riots that summer.

When you think back to where the country was politically in 1964 — Lyndon Johnson had beaten Goldwater in a historic landslide and Democrats had overwhelming majorities in the Senate and the House. Journalists were saying that the Republicans were finished for a generation. And two years later, they come back in the 1966 midterms, pick up dozens of seats in the House and in all these statehouses. Reagan is elected governor of California.

The light bulb goes off in Nixon's head that he actually may have a chance of coming back and runs for president in '68. And so when you think of everything that happened after that in American politics, 1966 is a hinge point. Remarkably, nobody had really written that book about '66 as just a turning point in American politics. So that was how I arrived at 1966.

If you had to distill it down, why did you call 1966 "the most dramatic shift in the long struggle for racial justice in America since the dawn of the modern civil rights era of the 1950s?"

It was two things. There was the political dimension of Black power. The challenge to the orthodoxy in the civil rights movement, personified by Dr. King — peaceful, nonviolent protest focused on passing legislation to undo Jim Crow and voting rights restrictions. A new generation comes along. They're younger, more northern and very impatient. And they're saying we don't want to be totally constrained by this discipline of nonviolence.

At first, they were talking about the right to defend themselves and a bolder political aim beyond just pushing for legislation to undo discrimination. They wanted jobs, housing and a focus less on opportunities for middle class Blacks. They were saying that this talk of integration is not helping the really poor Blacks in the South and northern working-class Blacks because white people really aren't interested in integrating with them.

Then, you had the Black Panthers by the end of the year on the West Coast focusing on the issue of police, saying California law allows us to arm ourselves and drive around and keep an eye on how the police are treating people in our community. So all of that was pretty radical and new and different on the political front.

But the other part of Black Power, which I think was even bigger, more enduring and its legacy was the cultural part of Black power.

Black consciousness?

Yes, this idea that being Black is not to culturally emulate white people or have a Black version of white society. It was a greater celebration of a distinct Black identity and for many people, getting in touch with the African roots of Black culture — the Afro, dress, insisting on being called Black as opposed to Negro.

It was also the beginning of an interesting movement that happened organically within Black America. Until the late sixties, overwhelmingly black Americans gave their kids names similar to the names of white American kids. Around this time, they started to give their kids from birth names that would stamp them with more of a Black identity. That eventually leads to innovation in music — hip hop — Afrocentric art, poetry and playwrights like August Wilson, all of that still pervasive today. It ultimately changed not just Black culture, but all of American culture.

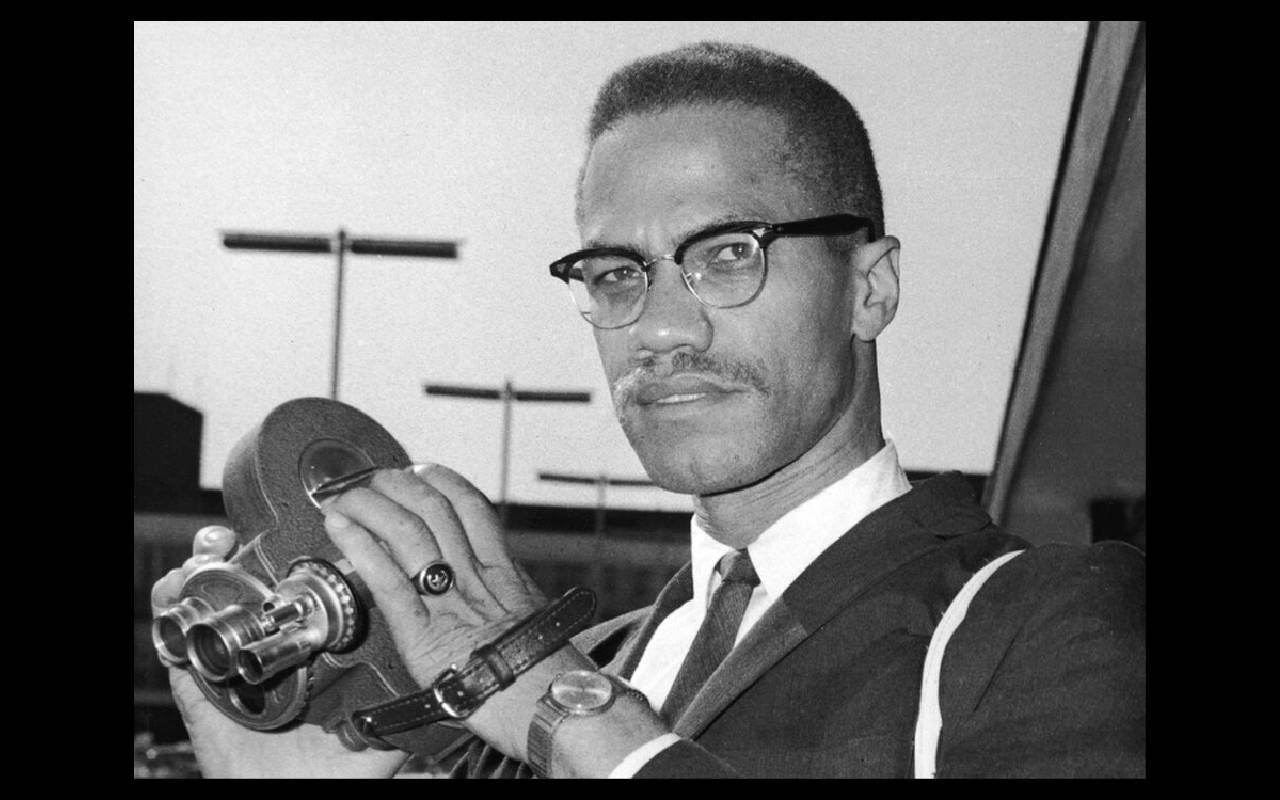

"If Malcolm X had lived, I think things might have turned out very differently because he might have provided leadership for this whole movement."

At the end of your book, you described the leadership vacuum in the Black Power generation "like children clinging to the memory of a lost father."

They were kids. They were immature. They did not have the maturity of a Dr. King or Malcolm X. When I decided to write about 1966 and Black Power, a lot of people would say, 'Well, yeah. Malcolm X.' I said, 'No, in fact he was assassinated in 1965.'

But it turned out that actually he is a huge presence, even in 1966 partly because all of these early Black Power leaders —Stokely Carmichael, Huey Newton and Eldridge Cleaver — thought that they were carrying on his legacy they all worshipped. And they all thought that one way or the another, they were doing what he what have approved of.

If Malcolm X had lived, I think things might have turned out very differently because he might have provided leadership for this whole movement. And he was held in such respect by all these young people that they would have listened to him in a way they were no longer prepared to listen to Dr. King.

There's a famous memo that FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover sent to his field offices in early 1967 explicitly saying we need to do everything we can to prevent the emergence of what he called a Black Messiah. He understood if a Black leader could emerge who could be recognized across the board, across generations and from the north to the south as THE leader of Black America, that could be very powerful and he wanted to prevent it, whoever it was.

"What our history shows us is that every time you have a period of advancement, you have a strong backlash against it."

Did King and Malcolm X share any qualities that were missing from the Black Power Generation?

What King and Malcolm X shared was a life of service and sacrifice. They were not cashing in or selling out. They had a moral authority that was based on that — in the same way Gandhi, who was a middle-class lawyer, gave up all of his material opportunities to live amongst the people and that gave him the authority he never would have had without that.

When Barack Obama was elected President in 2008, there was all this talk about a post-racial society as though he would somehow wave a magic wand and end racism. Despite all these firsts (a Black President of the United States, you were the first African American editor of Newsweek, we've now had Black governors and several Black Supreme Court justices), have we gotten any closer to that post-racial society since ten-year-old Mark Whitaker was reading the "Negro in America" cover story in Newsweek?

What our history shows us is that every time you have a period of advancement, you have a strong backlash against it. And so, after the Civil War and Emancipation, you had a brief period of Reconstruction, and that's followed by this fierce backlash in the form of Jim Crow and the Ku Klux Klan. This period that I write about —the 60's —starting with King and the civil rights movement and then the Black Power Movement, it's no accident that it's followed very swiftly by a right turn in politics — Richard Nixon and the Law and Order campaign, the George Wallace phenomenon, and as soon as President Johnson identifies the Democratic Party with civil rights legislation, the Democrats lose the South. And the Republican Party takes a rightward turn.

More recently you had Obama, the first Black president and then you had what seemed like a historic flowering of activism in the street in the summer of 2020, after the murder of George Floyd. Black Lives Matter, millions of interracial marchers seeking racial justice, talking about an era of racial reckoning. And here we are just a couple of years later and we're talking about banning books by Black authors, Black studies being canceled and banned. So I think what we really learned is it's not that there isn't progress, but every time you have progress, you're going to have a backlash as well.

It's not a straight line?

No, it's not a straight line. In my mind and I'm not sure it was even within August Wilson's mind, the playwright who came out of Pittsburgh. His play set in the 1960s, "Two Trains Running," is how I think of the history of race in America. It's two trains running. There's a good train and there's a bad train. And sometimes one pulls ahead of the other and then sometimes the other pulls ahead. But it's not one step forward, two steps back or two steps forward, one step back. It's two trains running. Both of them have been running since the nation was founded and are still running today. And you have to keep an eye on both trains. One train has definitely gotten a lot further down the track, the one that allowed me to be the editor of Newsweek and elected Barack Obama. And it's created a lot of opportunity. That train is certainly further down the track than it was in my grandparents' day.

But the other train is also moving down the track pretty fast, too. It's two trains running, even within the white population, in terms of support for racial justice. Two trains running, one train is further along, but the other train is racing along to catch up.