Why Our Culture Is Obsessed With Thinness

The author of 'Body of Truth' decries the 'thin is always better' mentality

How important is body size to our sense of intrinsic worth?

Consider this: A hospice chef in Wisconsin told a science journalist that many of the dying women who were still able to eat "refused bread, salad dressing, butter, chocolate, desserts and other 'fattening' foods."

You're on your last lap, and you think it is imperative to pass up salad dressing and say "no" to chocolate?

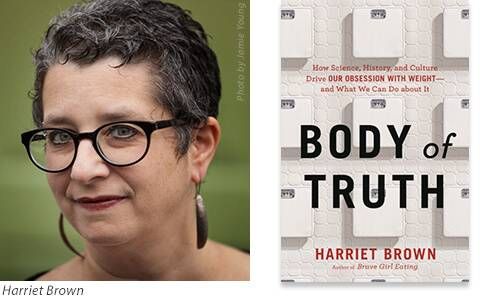

Harriet Brown, the journalist who heard that story, finds this a perfect metaphor for what she calls our country's "crazy thin-is-always-better mentality." Brown slices and dices that mentality in her new book, Body of Truth: How Science, History, and Culture Drive Our Obsession with Weight—and What We Can Do About It.

In a culture that says our self worth is determined by our appearance, bucking the imposed norm can be difficult.

"All our lives, the pressure to be thin comes from so many directions," Brown said from her home in upstate New York. "We are exposed to advertisements, the media is saturated with the message and it comes from the medical establishment, too. We can't get away from it."

Weighing the Evidence

Brown, 56, is a professor at the S. I. Newhouse School of Public Communications at Syracuse University. She spent almost a decade investigating our nation's obsession with body size. Brown interviewed doctors, therapists and sociologists. She spoke with hundreds of women about how they feel about their bodies. And she reviewed reams of research on weight loss, obesity and eating disorders.

Fully aware that 75 percent of women in the U.S. report "disordered" eating behaviors, Brown concludes that we are doing ourselves great harm when we focus on weight as a proxy for health.

"There is convincing evidence that staying at a higher, stable weight and appreciating your body is good for your health," Brown said. The Mayo Clinic goes so far as to suggest that stressing about your body size puts you at risk for – wait for it – weight gain. And remember that historically, just between 3 and 5 percent of people who do lose weight keep it off for five years or more.

Make no mistake about Brown's intentions. Nowhere in Body of Truth does she recommend overeating for the sake of overeating. She is in favor of eating healthy foods and repeatedly praises the benefits of physical activity. What Brown wants is to start a conversation.

Time for a Change

"I would like to change the conversation in this country about weight. Part of what reinforces cultural ideals about weight – in addition to ads and medical professionals – is the conversations we have with ourselves and with each other. Maybe the book will start to shift those conversations, and that will be helpful."

Brown added, "I'm not trying to tell people what to think. I am saying do think for yourself. Here is some evidence – make up your own mind."

In the book, Brown presents expert testimony that:

- dieting and weight cycling (aka yo-yo dieting) leads to unhealthy physical and psychological effects

- physical and psychological damage comes from being rigid, chaotic and fearful about eating

- people unhappy with their weight are more likely to give up on health-positive activities than heavy people who are satisfied with their weight

- whether you diet or don’t, you are going to die

Brown writes about the $60 billion diet industry and the $250 billion beauty industry. And she writes about the medicalization of obesity.

How Obesity Became a Disease

Time for a quick history lesson: In 1920, weight-loss drugs were first introduced. In 1943, an insurance company drew up a list of desirable weights for adults that Brown says were "based on nothing." In 1949, some doctors positioned themselves as "obesity specialists."

And in 2013, though the American Medical Association's (AMA) own Common Science and Health Committee recommended against defining obesity as a disease, the AMA moved forward. That meant that obesity — though it is not a medical disease and is not always harmful — required medical intervention.

By their own admission, many doctors are biased against fat people, and that keeps many people —primarily women — out of doctors' offices. "You would think doctors could parse the differences between weight and health for individuals," Brown said in the interview. Her experience has been that they do not, that today only one size is best for all: thin.

"A friend and I are the same height, and though our weights are different, we both are healthy," Brown said. "When I have been thinner, I like the way I look and I get cultural reinforcement, but I am tired, weaker and obsessed with food because I am starving myself. Today I choose to focus on what I do rather than what I weigh."

Older Women Can Lead the Way

One study Brown cites concluded that thinking critically about our cultural body ideals is a path to sanity, and many of us may be on that path already. A 2014 Gallup poll found that at 65, more Americans reported feeling good about their appearance than middle-agers do.

"When I turned 50, I expected it to be horrible, but a sense of liberation took me by surprise," Brown said. "I decided I can do what the hell I want, live the way I want to live, be less vulnerable to messages about what I should be or look like."

She continued, "That confidence that comes with age — we need to use that, and combine it with critical thinking. When we are less affected in a minute-to-minute way by cultural expectations, we can step back, take time to think critically. That was a big revelation to me."

Brown noted that research shows that some of us also moderate our obsession about weight as we get older.

"We begin to derive more self esteem from within rather than from without," Brown said. "That gives older women more power, an ability to see outside of the box we all are in so much of our lives, to see that we don't have remain wedded to cultural ideals of what is healthy and what is attractive."

Laughing, Brown mentioned Candice Bergen's new memoir, A Fine Romance.

"In the book, she writes that she's gained 30 pounds over the years, so she is fat for Hollywood," Brown said. "But Bergen says she doesn't care, because she likes to eat — and food is good."

Put Down the Burden Today

The mother of a daughter who suffered from anorexia (see her book, Brave Girl Eating: A Family's Struggle with Anorexia), Brown is deeply concerned with the messages young girls receive about body image.

"From an early age, you must be culturally approved, and 'pretty' is identified as 'thin,'" she said. "The messages are relentless, and very 'one note.' It's so sad. I remember my grandmother had women friends, and the one or two who were larger were very much part of the group. People have always come in a range of sizes and shapes."

What's different now is that the norm has gotten narrower, literally. "A recent Miss America contestant got praise for not being as thin as the others," Brown said. "At size 4, she was the large one."

So how do we go from being obsessed with the size of our bodies to loving and accepting ourselves as we are?

Today, we take up Brown's challenge to change the conversations about weight and health with ourselves, our families, our friends and our doctors. Here, in the cocktail hour of our lives, we put down the burden of self-recrimination we've carried for decades.

And we fully savor that occasional morning muffin.