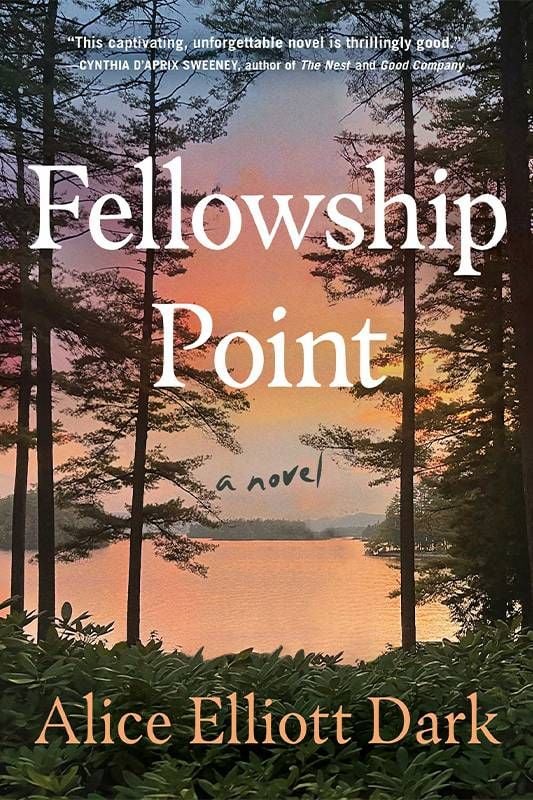

The Novel Way Two Older Women Face Aging

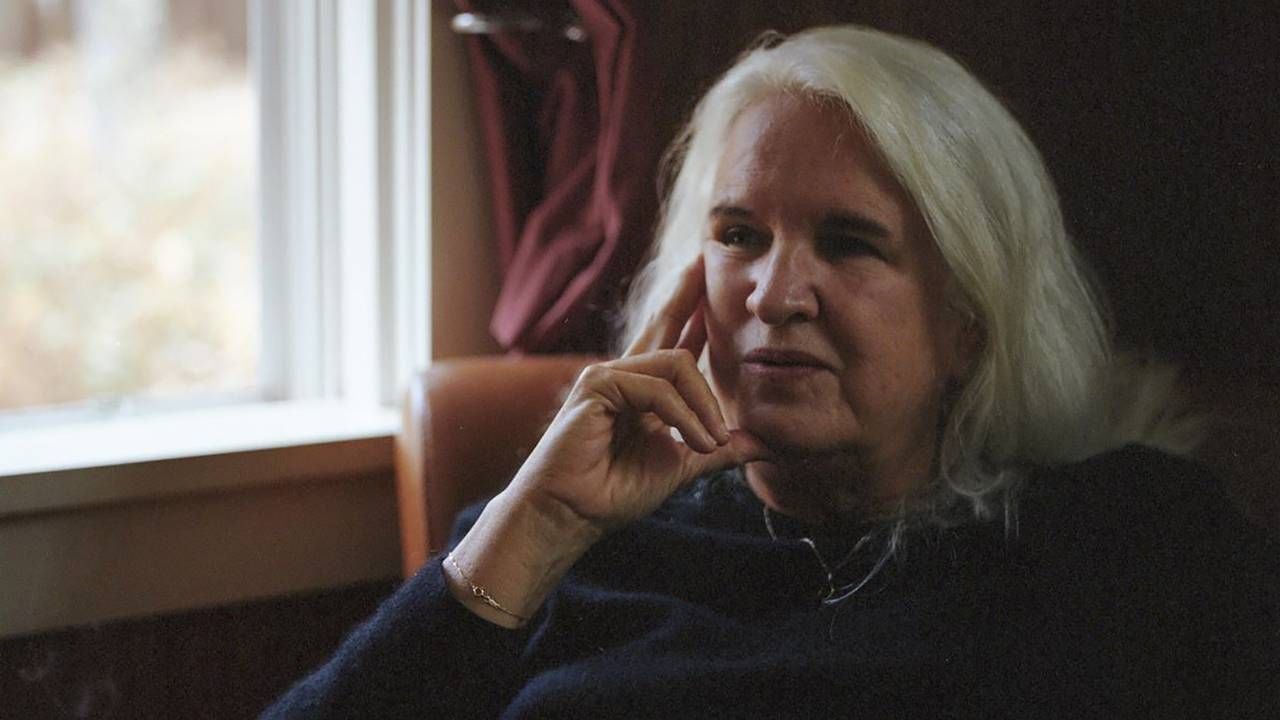

Alice Elliott Dark talks about her new novel 'Fellowship Point' and characters who are 'in control of themselves and active'

Alice Elliott Dark's riveting new novel, "Fellowship Point," features two octogenarian friends. As Agnes and Polly wrestle with the challenges of aging, from intergenerational conflict and social invisibility, to buried secrets and legacy considerations, Dark presents a portrait of two women who, though very different in their life choices, remain tightly bound by their ongoing vitality and determination to maximize the time they have left.

An associate professor of English at Rutgers University-Newark, Dark is also the author of the novel "Think of England" and two collections of short stories. One of those stories, "In the Gloaming," was made into an HBO film starring Glenn Close.

Next Avenue recently spoke with Dark, 68, about the aging issues at the heart of "Fellowship Point."

Next Avenue: It's very unusual for a novel to revolve around main characters who are in their eighties. What made you choose this landscape?

Alice Elliott Dark: I chose it because I really like old women. They've always fascinated me. As a child, I had two great-great aunts we visited every Sunday morning. I was enchanted by their lives. They were happy. I also liked my grandmother and her friends. They seemed to have a kind of independence and freedom that younger women didn't. I wanted to show two women still completely in the middle of life, physically active, not shying away from being old, but not done. I feel strongly that older women are unappreciated and marginalized in our culture. They're written off. It's starting to happen to me.

"I wanted to show two women still completely in the middle of life, physically active, not shying away from being old, but not done."

During the ten years that it took you to write this book, did issues come to the foreground as a result of your own aging experience that then made it into your characters' lives?

There are moments where Agnes chooses not to drink anything, worried about where the bathroom is. That definitely became a much bigger factor in my life in that period. Also, I felt the gap closing between myself and my mother, watching her have to make decisions about having to give things up, including a house she loved. My feeling strengthened that she should be able to make her own choices and not worry about leaving money for children. Polly's children pressure her to sell a home she loves.

Agnes and Polly are clear-minded and vital to the very end. Were you looking to refute the popular notion of failing mental and physical faculties?

Yes. I know plenty of people that old who have no failing faculties beyond forgetting a name. It just happens when people get tired. But that's not failing faculties, it's the body having different abilities. I wanted Agnes and Polly to be in control of themselves and active. I wanted a sense of physical movement, of them meeting outside, always in motion.

These two women, who have known each other since the cradle, often understand each other better than they do their family members. Why did you showcase friendship?

Part of it is because I went to a girls' school, K through twelve, so female friendship has always been very central to my life. Close friendship is also something I've observed in older women. These aren't lesser relationships, but often they get trumped by marriage. Agnes and Polly have a powerful friendship, but with Polly, her husband still comes first. Such friendships are such a deep part of me that I take it for granted that women are loyal to each other.

For decades, these two best friends harbor secrets, even from each other. They grow more candid as they approach enter their final years. What do you think inclines people to confront and voice their truths as they approach death?

Even at my age, if you asked what I'd like more than anything, it would be to know the truth about my own life. I think it's the natural falling away of the defenses and false narratives that young people seem to need to keep going. I feel so much less need to have my version of these stories than I did when I was younger. I just want to honestly see my role in all situations. I don't think that's unusual among older people. At the end of our lives, we have more time to reflect and not hang on to the same old stories. We leave the hurt feelings aside. We want to know what really happened and is there a remedy.

Agnes has young friends right up through her late eighties. What are you hoping readers will take from these intergenerational relationships?

It goes beyond humans into the animal and natural world. Agnes befriends lots of different creatures, including a teenager. My point is that it's not over, that if, like Agnes, you remain open, relationships can develop at any moment.

"People don't give children credit and they don't give older people credit. They act like only the stage between twenty and sixty is fully formed."

Agnes observes of herself that "she'd reached the stage where no one would hear her even if they heard her." Polly feels that "she was shown and told about her diminished status at every juncture." Talk about the invisibility of aging.

It's a waste of resources for our country. In contrast to a lot of cultures that venerate old people, we don't. When you look at COVID, the top outbreaks are always in nursing homes. It shouldn't be that way. There should be a more realistic understanding of what the needs are. It bothers me that when I go to a doctor's office, their assumptions about me shift when they understand that I'm still a working professor. If you're not making money in our system, you're not considered viable.

Mild-mannered Polly makes this bald statement about aging: "No one wants age to be the most important thing about her." What do people fail to understand about their elders?

People don't give children credit and they don't give older people credit. They act like only the stage between twenty and sixty is fully formed. People are just as developed at the other ends. Why don't middle-aged people learn the language of older adults? Why don't they ask, "What is it like?"

This book is finely attuned to legacy: what we leave behind, how people will remember us. Why is this issue so important as we age?

In working with people's wills, I've come to understand how important it is to older people to leave behind a clear message. Often, it's in terms of things, but it's still a message to your children, like, 'I love you all equally, or I understand your circumstances are financially different, so I'm going to recognize that.' There's an implicit message in legacy. It's almost imagining yourself not here, imagining how you want your children to understand what you're leaving behind.

Did writing about older women make you feel better about aging?

Yes, not that I didn't feel good about aging before. I've always looked forward to it. But focusing on things that were potentially going to happen, and thinking about my characters being active, did help.