Writing Vietnam

The catharsis of writing their memoirs helped two Vietnam veterans heal

"Write hard and clear about what hurts." — Ernest Hemingway

What is that place where we store our memories? Is it a virtual file cabinet filled with sounds and pictures and smells? Does it stay in permanent storage, or do we visit from time to time to honor or mourn what happened long ago?

For military veterans who served in Vietnam, the past few years have been a time to open the memory vault. Their ages and their situations motivate them. Decades after their service, they feel free to document and publish their experiences.

"I wanted my family as well as my friends to know what the Vietnam war was like for me."

The memories are spilled out, strewn across the floor, then organized into chapters and scenes. It's the birth of a memoir. It's how trauma is laid to rest.

The catharsis of a memoir is not limited to veterans. Writing offers a healing power that can benefit anyone who has experienced trauma.

Laying Trauma to Rest

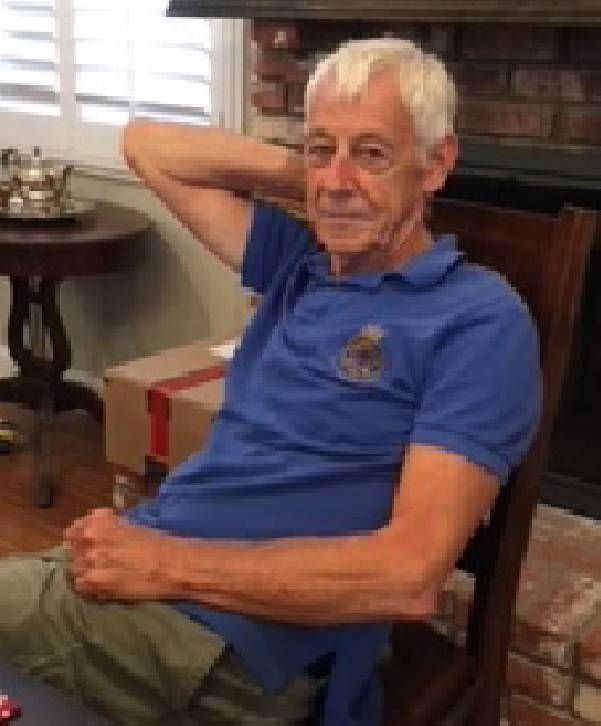

Norman Hile, a retired attorney in Sacramento, California, felt he had held on to his memories for long enough. His memoir, "Keeping Each Other Alive", details his training as an artillery officer and his combat tour in a hotbed of the war.

"I wanted my family as well as my friends to know what the Vietnam war was like for me," Hile said. "I also wanted there to be a record for anyone writing a history of the war."

There was a lot that Hile kept to himself until he compiled his recent memoir. "With the exception of one or two incidents (such as almost being court-martialed for refusing to adjust artillery fire onto a village of women and children and what horrible conditions we lived in when in the field), I had never discussed with anyone most of what I wrote," he said.

Hile said he "sanitized" the letters he wrote to family from Vietnam. Despite his omission of graphic details, he was glad the correspondence was saved. "Fortunately," he said, "those letters gave me a very useful timeline of events for the book."

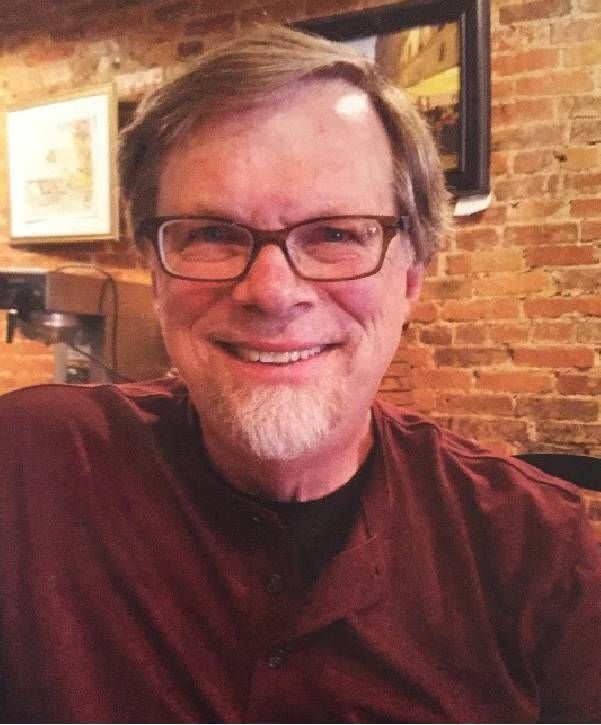

Angelo Presicci is a retired teacher in San Francisco who served as a commander with the 11th Armored Cavalry. His book, "Fighting the Bad War," is fiction based on his experience as a gay soldier in Vietnam. Unlike Hile, Presicci started writing in the late 1970s, just a few years after the fall of Saigon.

"I felt the distance since the fall was ripe for reminding ourselves of that history," he said. "It has never stopped being the right time."

As he wrote, Presicci explored the depth of his memories. "The unraveling narrative revealed more of what I had stored away, what I had not spoken, not even to other vets. The writing stirred memories that brought nuance and details to life."

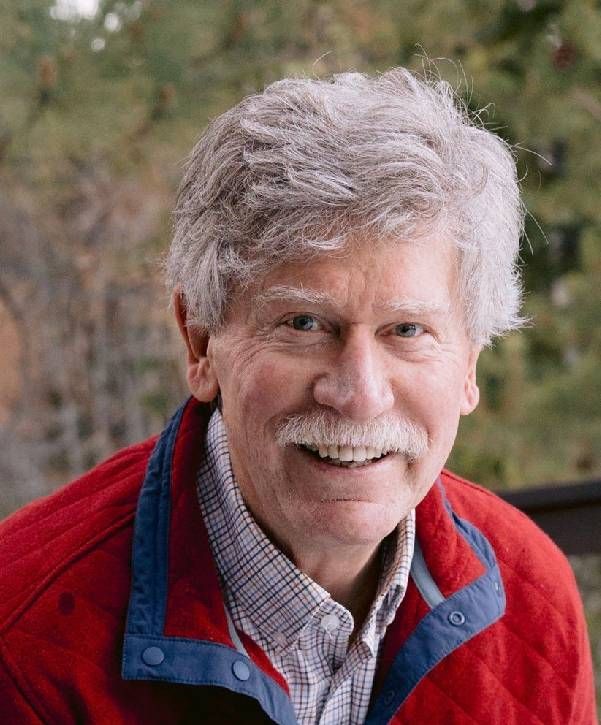

"Storytelling is the way we make sense of things," according to David B. Seaburn, a psychologist, author, minister and contributor to Psychology Today. "Writing is an even finer distillation."

Trauma has mental and physical effects on our health, Seaburn explained. "Trauma often resides in the mind and body beyond language. Putting language to the trauma is one way of taking some control. Talk therapy doesn't work for some people. Writing is a good alternative. Journaling, writing specifically about an experience, memoir are all effective methods."

Soldiers Have Told Stories Throughout History

The written word helped retired U.S. soldiers tell their stories almost a century before Vietnam. Dillon J. Carroll, author of "Invisible Wounds: Mental Illness and Civil War Soldiers," pointed out the trend.

"The 1880s and 1890s was a particularly productive period for Civil War Veterans writing memoirs," he said. Perhaps the most famous, according to Carroll, came from Sam R. Watkins. "Co. Aytch: A Side Show of the Big Show" was published in 1900.

The American Revolution also had its standout author. Joseph Plumb Martin's narrative about his service has been published under several titles. His work has been quoted by historian David McCullough, and excerpts have been used in television docudramas.

Watkins and Martin may not have had a knowledge of catharsis. They told their stories in the medium that seemed most natural to them. Seaburn explained that writing offers a safe default communication style.

"People dealing with trauma are faced with the challenge of making sense of their experience," he said. "Talking about it, for some, may be too frightening. They may feel they can't formulate the words. But writing is different. It is more private. The writer can be more honest with themselves."

Presicci found writing helped him sort through his memories. He also released blame through his fiction. "I had thought my stories would reflect my anti-war sentiments. But while writing, I understood that to treat all characters fairly, I would have to release those characters, American and Vietnamese, to make their own way," he said.

The Perspective of Time

Hile said he found the process of writing his memoir painful at first. "It brought on symptoms of PTSD," he said, "but it also made me appreciate how lucky I was to have survived and to have had a full, rewarding life afterward."

Hile had a good reason for waiting so long to write his book. "For years, it had been easier not to stir up so many painful memories. But if I was ever going to write my memoir, at age 75 I knew I had to do it now."

For Presicci, the passage of time presented a change in perspective. "I always thought memories were a person's invention to justify one's existence. It surprised me that the memories were so layered."

Anyone can benefit from writing about personal experience. Seaburn points to the growing body of research on the positive effects of writing on brain and body functioning.

"As little as fifteen minutes of writing can improve mental and physical health for anyone," he said. "Writing routinely can improve hypertension. It can increase the number of CD4 helper cells needed to fight HIV. Writing about yourself and your experiences can improve mood disorders, reduce symptoms in cancer patients and improve health after heart attack."

Presicci said the writing process changed his life. "Vietnam was my zeitgeist. Writing about my military experience helped me shed my anger and frustration. It helped me explain myself to myself."