The Day the Blues Came to Town

How a constellation of legendary American blues musicians came to play a storied concert in an abandoned English train station

May 7, 1964, was a damp day in Manchester, England, a large industrial city once dubbed 'Cottonopolis' for its global role in textile manufacturing. Around 7:30 that evening, 200 excited travellers gathered under the great, Victorian single-span vaulting roof of the city's Central Station to board a steam locomotive hired for the occasion. They did not know its destination.

The train turned South, chugging along a disused branch line through the suburbs for just a couple of miles before drawing to a stately halt at the long-abandoned Wilbraham Road Station, a handsome, red brick single story building.

The show was the brainchild of American promoter and producer George Wein, a legendary figure best remembered for his vital role in creating the Newport Jazz Festival.

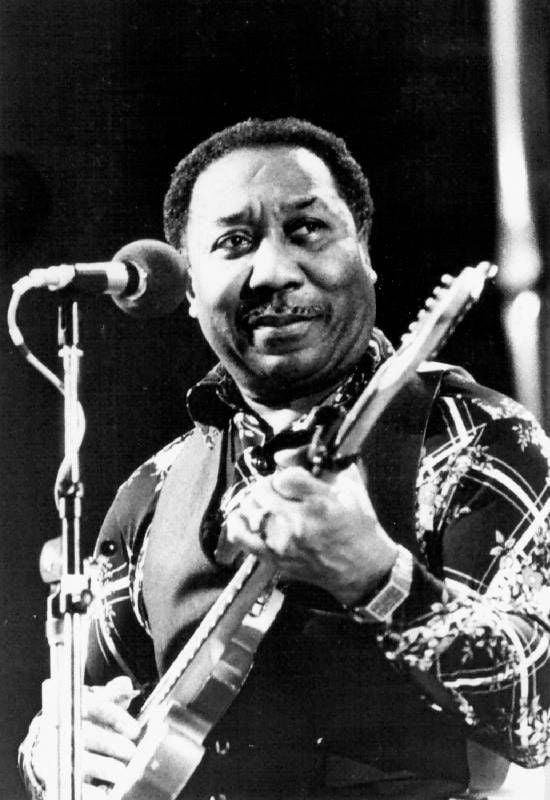

As the passengers disembarked and began to move toward rows of temporary seating, the singular figure of an African-American man, guitar in hand, serenaded them with a stirring rendition of "Blow Wind Blow."

The man was the pioneering guitarist Muddy Waters, and this was the day the blues came to town.

A Legendary Lineup

The Blues and Gospel Caravan international tour featured a spectacular cast of artists. Alongside Waters were the great harmonica/guitar duo Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee, blues and gospel multi-instrumentalist Reverend Gary Davis, famed New Orleans jazz singer Cousin Joe and the pioneering gospel/rhythm and blues guitarist, Sister Rosetta Tharpe.

The show was the brainchild of American promoter and producer George Wein, a legendary figure best remembered for his vital role in creating the Newport Jazz Festival, and for transforming the very idea of the music festival into an important cultural phenomenon.

The Caravan's tour manager was Joe Boyd, a 22-year-old white man fresh out of Harvard with a penchant for the blues. Boyd would go on to great fame as a record producer and writer, working with Pink Floyd, Nick Drake, R.E.M. and a host of other stars. Back in 1964, this was his first ever job.

"I walked into George Wein's office on Central Park West," Boyd recalls, "he was looking for a tour manager. George listened to me talk about blues for perhaps 15 minutes, then motioned to a desk with a telephone and told me to get started finding a bass player. That moment was the beginning of my life in the music business."

In the U.K., groundwork was laid by another young talent, producer Johnny Hamp of England's Granada Television company. Hamp had a background in the entertainment business, having toured as a boy with his father, a stage magician with the professional name The Great Hampo.

After a stint in the Royal Air Force, Johnny moved into promotion, working with acts such as Frank Sinatra and Gene Vincent. In 1962, he organized the television debut of a new band from Liverpool: The Beatles.

Evoking the American South

For the Caravan show, Hamp decided to pull out all the stops. The evocative imagery of steam trains has a long association with the blues, and Hamp previously hired rolling stock from the railways to use as the backdrop for the singer Little Eva when she performed her hit, "Loco-motion."

When sources tipped him off about the disused station, Hamp jumped at the opportunity. One canopied platform was decked out with seating. Across the track, the other he transformed into an image of the rural deep South, complete with bales of cotton and live chickens and goats.

Boyd, meanwhile, had put together a crack line-up of supporting musicians, including drummer /harmonica player Willie Smith and bassist Ransom Knowling. A native of Arkansas, Smith had been inspired to pursue a life in music after attending a Muddy Waters concert at the age of 17, in 1953.

By 1961, he had become a regular member of Waters' band, and would later play on all the latter's Grammy Award-winning albums. Knowling by this time had featured on a long list of celebrated blues recordings by artists such as Big Bill Broonzy, T-Bone Walker and Arthur Crudup.

An enduring rumor has it that, having driven up from London in a rented van on that day, future guitar heroes Eric Clapton and Jeff Beck, together with The Rolling Stones' Keith Richards and Brian Jones, had snuck in to watch the event.

According to Boyd, writing in his autobiography, "White Bicycles," "the heart of the tour was Muddy, a man of gravitas and dignity." Boyd also held a deep appreciation for the artist whose performance would steal the show in Manchester, Sister Rosetta Tharpe.

Born Rosetta Nubin in Arkansas 1915, Sister Rosetta Tharpe's influence on the evolution of popular music can't be overstated. Aged six, she began performing gospel songs with her mother. By 1938 she had a string of hit singles. They were groundbreaking works, mixing up-tempo blues with gospel-tinged lyrics. As a guitarist, her highly rhythmic style, bluesy and hot, bending strings and embracing the use of amplification and distortion, laid the groundwork for rock 'n' roll.

Sister Rosetta Improvises

In the Manchester May 7 show, following two numbers by Cousin Joe, the heavens opened, and a heavy downpour began. The stage was set for a magical moment. Arriving by horse and carriage, Tharpe stepped elegantly onto the platform and proceeded to cakewalk along it, arm in arm with Cousin Joe as the band played.

In an impromptu change to her scheduled song, Tharpe started in on a joyous rendition of the old time spiritual, "Didn't It Rain." Brimming with irrepressible soul and energy, she mesmerized the audience. Muddy Waters followed, and then a trio of songs from Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee, before a final encore from Tharpe leading the whole ensemble in a rousing rendition of "He's Got the Whole World in His Hands."

Long after the applause died down, the audience climbed back aboard the train, the instruments were packed away and the television crew departed, silent echoes of the spirit of the blues must have echoed around the station, a wondrous afterglow of a never-to-be-repeated event.

The Station Is Gone; the Music Lives On

An enduring rumor has it that, having driven up from London in a rented van on that day, future guitar heroes Eric Clapton and Jeff Beck, together with The Rolling Stones' Keith Richards and Brian Jones, had snuck in to watch the event. Whether or not this is true, it's certain that that, without the blues artists on the railway platform that day, rock as we know it would not exist.

Full footage of the Manchester concert was transmitted on August 19, 1964, to 12 million viewers. Today, Wilbraham Station is gone, demolished to make way for housing, though residual brickwork from the platform survives, as does the Station Master's house, now a private residence.

Perhaps, if you stand there on a rainy night, you might yet hear the distant strains of Sister Rosetta Tharpe. If not, turn on your radio. All modern music owes her a debt.