Alan Alda Talks About His Adventures in Communication

The famed actor's book presents research and advice on a topic dear to his heart

When Alan Alda calls you on the phone, you know immediately that it's him and you realize right away that he's as charming and relatable as you always hoped he would be.

And, as it happens, he is an expert on the topic of "relating" — a word borrowed from the acting and improvisation world to explain the optimal way of communicating with other actors.

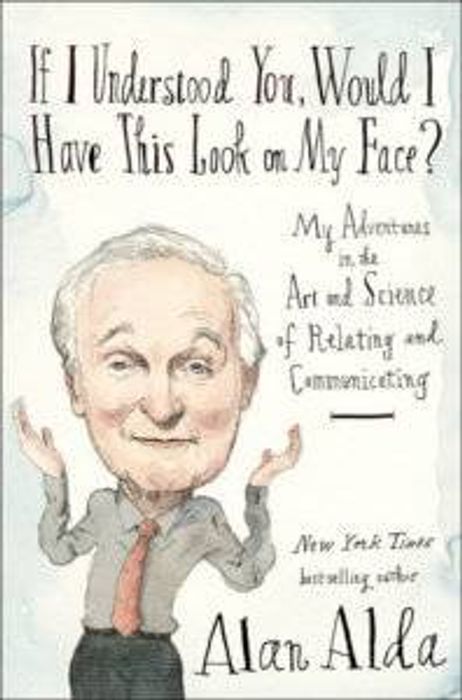

Alda, the multiple Emmy and Golden Globe Award winning actor known for playing Hawkeye Pierce on M*A*S*H and Sen. Arnold Vinick on The West Wing, has published a new book on the topic of communication and relating, If I Understood You, Would I Have This Look on My Face? My Adventures in the Art and Science of Relating and Communicating, released by Random House this week.

What is relating? "It's being so aware of the other person that, even if you have your back to them, you're observing them. It's letting everything about them affect you; not just their words, but also their tone of voice, their body language, even subtle things like where they're standing in the room or how they occupy a chair," Alda writes in the first chapter. "Relating is letting all that seep into you and have an effect on how you respond to the other person."

Communication is key to our ability to live with one another, explains Alda, who found a passion for helping scientists better communicate their work.

He did this first through his duty as host of PBS' Scientific American Frontiers, which ran from 1990 to 2003 and featured Alda interviewing scientists from a variety of fields.

He also did it through helping to establish and serve on faculty of the Stony Brook University Alan Alda Center for Communicating Science (founded in 2009 and renamed in his honor in 2013), work which he describes at length in the book.

I recently interviewed Alda about his book and his passion for better communication among all of us. Highlights:

Next Avenue: One thing I really liked about your book is that you do what you wrote about: You lay out the science and research and other people's results in plain, understandable language and add your own real-life examples.

Alan Alda: Thank you. It’s not a doctoral thesis. I don’t make an attempt to cover the literature entirely, but talk about what I came across as I explored it. It’s really a personal quest.

You mixed up the research on communication and relating with your own lived experience and also what you’ve learned. Can other people learn to do that, too? Even if you aren’t an expert, can you learn to lay out theories and research in a way that’s clear and easy to understand?

If I can do it, then other people can do it. To the extent that I could do it. The trick is to not pretend to know more than you know.

What really smart people are aware of, more than the rest of us, is what they actually don’t know. A very poor, destructive kind of ignorance is to think that everybody possesses your same ignorance — that what you know is all there is to know. It’s really important to keep in mind (and I try to keep it in mind) whenever I talk about a big idea. I try to remember that I’m probably only grasping one aspect of it at that, and there’s probably somebody who is more authoritative on the subject.

That’s why I kept the book a personal account. Overall, I think I came up with something really interesting and useful, but I don’t pretend to know everything about the subject.

You have a passion for helping scientists communicate. I couldn’t help but think as I read the book how crucial this message is in this time of climate change denial even in the highest offices of government. Do you think scientists are beginning to see why it is so important for them to better communicate their work to the public?

I think they really see it now. When we started the Center almost eight years ago, first of all, Stony Brook University was the only university that was interested in teaching communication to scientists. And even on the Stony Brook campus, we couldn’t get some department heads interested in teaching their students. Now we can’t accommodate all of them and I’m trying to raise money to accommodate all of the people who want to take training with us.

It's such a unique approach, and I can't help but think that all experts and graduate students should go through the training.

We've developed our own version of (curriculum) at Stony Brook. We carry the improvisation all the way through, from the improv to the writing. It probably sounds weird that you would use improvisation — which is a face-to-face thing — to help with writing, but it actually helps enormously to be able to keep in mind the person you’re writing for. So that you don’t get past where they are with understanding you.

And then what we found was that while we were teaching scientists, if we adapted it just a little bit, we could teach doctors and medical professionals. And I began to realize that there wasn’t any area you couldn’t improve with better communication.

In fact, I was on the tennis court one time and a physicist came over and said, 'I know about your work, and you have to train other disciplines, too. My wife is an art historian and I can’t understand a thing that she says.'

It's really for everybody — parents and children, married people, lovers, friends — people trying to be clear with one another and not fight over trivial things. Or at least fight better.

Fight better?

One of our exercises really calls that into play — where you hear a person ranting about something and then you have to introduce that person to someone else based on all the good things that are under the rant, rather than the negative things. If you do that while you’re having an argument with someone, it really short circuits the argument because you see what the good impulses are.

At this time in the history of our country, when there’s so much divisiveness, communication in general seems especially important.

It’s true. Nothing is accomplished by demonizing the other side regardless of who started it. When you think about the fact that we are all Americans and we all want the country to prosper, just because we have different ways of going about it doesn’t mean we have to call each other names. We’re not going to get anything done and we haven’t gotten anything done for years.

You write in the book: 'There’s no failing in improvisation.' And you point out that there’s no formula. I bet it’s really hard for a scientist or an expert to figure that out — and probably for everyone, really.

It takes a bit of a willingness to leap. To get into the improvisational way of thinking. When we have a chance to work with people in a workshop, we can make it much easier for them because we start at such a basic level that it isn’t scary for them at all.

The way I first started (in comedy improvisation performances), they threw us on stage in front of an audience and we had to make up hilarious scenes in front of people, and that can drive you crazy. I remember one opening night, one of the actors pretended he had fallen and hit his head and couldn’t go on. It was so scary. But the thing is, not everybody can go to an improv class and not every improv class can lead to this ability to connect to another person. That’s comedy improv and that’s different.

The kind of stuff we do at Stony Brook and what I describe in the book is something that promotes relating to the other person.

That’s why I came up with that thing in the middle of the book where I started wondering if there was some personal, emotional gymnasium that I could create where I could practice improv with people throughout the day and they wouldn’t even know it.

There's a scene in the book in which you're doing this with a cab driver — you're kind of trying to read his motivations and offering to make his picking you up and giving you a ride a little easier.

(Laughing) I had to take a rest for awhile after that.

That was a small interaction.

But it was a basis. The thing is, when Matt Lerner, the psychologist, did that study showing how much your empathy improves after a week of reading other people like that, that encourages me. It might not be a bad idea to practice that. It might not totally replace the improv experience, but it is an experience with another person. And that’s really important.

The one thing I’m pretty sure about is that you can’t transform yourself by reading a bunch of tips. I could say, 'practice interactive listening' where you let the other person know you heard them. And that’s a good idea. But if it’s not done in having a real connection with the other person, you can actually mess it up. It can sound hostile. That’s one reason why I say it is not a formula. I really try to avoid tips.

It sounds kind of exhausting to do the kind of relating and empathetic communicating that you’re talking about all of the time.

I don’t know. I’ve found there’s a wonderful feeling of reconciliation, a peaceful feeling that things are less tense when two people are really connecting to each other, looking at each other, hearing each other when each knows he or she has been understood by the other. In fact, it feels so good I wonder why it isn’t self-reinforcing. Why aren’t we all expert in that? Why do we need a book on this?

I was thinking about your work on Scientific American Frontiers on PBS, and it was groundbreaking — especially early on, when that kind of show was more unusual. In the book, you talk about how you got better at hosting that show as it went on because you realized you weren’t listening to the scientists in the way that you should’ve. But you have a warmth and a humor that seems like something that you’re just born with, and people who have those things just automatically seem better at communicating. But is that true? Can it be taught?

I think that what I got better at as time went on was being myself, and the interaction I had with the scientists helped them to be themselves.

If somebody is being himself or herself and the self they're being doesn't happen to be funny — that doesn’t matter. They can still be interesting and engaging. The more you let out all the parts of yourself that are unguarded and not necessarily what you want to show company when they come to call, the more texture of the real person comes out. That’s more interesting to look at. And I think it brings it out of the other person who you're talking to.

At Next Avenue, we talk a lot about 'encore careers' — what you add to you repertoire and do after you retire. You’re still acting, but you're clearly also doing this new line of work. I’d love to hear how you got onto this passion.

It’s the same way I did everything in my life — I followed my nose. Whatever interested me, I put my time into.

When they asked me if I would host the Scientific American Frontiers show, I said 'Yes, but only if I can interview them on camera,' which was not at all what they had in mind. They thought it would be more of a narration. But I wanted to learn from the scientists, and that got me involved in wanting to help them communicate better, and then I branched out into wanting to help doctors.

And then after beginning the program at Stony Brook, I branched out and started a company called the Alda Communication Training Company (or ACT for short), and we’re setting up workshops in corporations. Our first project is women in business.

So I haven’t stopped anything that I’ve been doing. I’m just doing twice as much as before, and it’s all things that I want to do and that I’m eager to make some contribution to. It’s a lot of work, but I’m enjoying it very much. And as you said, I still act.

What’s next for you in the next five to 10 years?

I have no idea. I never plan ahead. Russia and China have proved that five-year plans don’t work. The whole world changes so rapidly. If you have a five-year plan and stick to it, I think that within the first three months, you are already behind the eight ball.