Artist Mike Henderson: Before and After the Fire

'Before the Fire: 1965 - 1985' is Mike Henderson's first U.S. solo museum exhibition in 20 years

When Mike Henderson showed up at art school in 1965, the only one he found that would accept a Black man, he felt like he had come home. After getting his BFA from the San Francisco Art Institute (SFAI), he taught for more than 40 years at the University of California, Davis.

Now, a show of Mike Henderson's work, Before the Fire: 1965-1985, is at UC Davis' Jan Shrem and Maria Manetti Shrem Museum of Art. It's the artist's first U.S. solo museum exhibition in 20 years, featuring his early protest paintings as well as later abstract work.

Henderson was born in Marshall, Missouri in 1943 and grew up with seven siblings in a house with no plumbing. His mother was a cook and his father worked as a janitor. The Ku Klux Klan were a presence in town, marching in parades, and a teacher told the Black students he was just going to show them how to wait tables. No one around him except his aunt encouraged his interest in art, which started when he was a little boy.

"I remember just staring at the paintings in church or in a magazine or comic book ... My father used to yank them out of my hand."

"I remember just staring at the paintings in church or in a magazine or comic book," he said. "My father used to yank them out of my hand saying, 'You're not even reading the book, you're just staring at the pictures.' What I was trying to figure out was how this guy made Superman look like you're looking up at him on this page — about perspective, you know, and where is the viewer."

Henderson shined shoes at a hotel and took a correspondence course in drawing. He put his work up at the shoeshine stand to sell to customers. One of those customers who admired his art bought him a ticket to see a Van Gogh exhibit at the museum in Kansas City. The paintings, particularly The Potato Eaters, which he saw depicting the kind of poverty he knew, made a big impression.

Having made it to art school in his early 20s against such long odds, Henderson seemed determined to learn everything he could, and in the Manetti Shrem show, his ambition and range are apparent.

"I just approached every moment like, 'I might not be here tomorrow.' I remember walking down the steps going to the painting studio one day and I realized it was the wintertime, and it wasn't snowing. And I thought, 'Wow, it's 10am in the morning, and I'm going down to paint. Back in Missouri, I'd be out looking for some job to shovel snow to make a few bucks," he said.

The fire in the show's title is literal — in 1985, one broke out in Henderson's home studio.

"It was all about working and for me, it was double or even triple because I didn't know what it took to be an artist. So how do you know when you even are an artist?'"

Undoubtedly an artist, Henderson has received two Guggenheim fellowships and his paintings have been exhibited in institutions including New York's Museum of Modern Art, Whitney Museum of American Art, and Studio Museum in Harlem, the San Francisco's Museum of Modern Art and the de Young Museum, Sacramento's Crocker Art Museum, and Chicago's School of the Art Institute.

Along with painting, he's made short, experimental films, which he decided to do after going to a memorial for Martin Luther King and wanting his paintings to move to make them more powerful. Henderson is also a blues guitarist who has shared the stage with artists including John Lee Hooker, Big Joe Turner, and Lightnin' Hopkins.

The exhibition, designed by George McCalman, who wrote Illustrated Black History, includes some of Henderson's music, with a space adjacent to the exhibition called Cosmic Strut (named for one of Henderson's records), where his music plays softly and visitors are invited to reflect on the show. Some of Henderson's films, such as Pitchfork and the Devil and The Shape of Things, are also in the show.

Henderson became a professor at Davis at the invitation of William T. Wiley (he turned the offer down at first, not wanting to move to another small town, but decided to stay in San Francisco and commute). Along with Wiley, the Davis art department then included heavy hitters such as Wayne Thiebaud, Manuel Neri, and Roy De Forrest.

Henderson loved working with these artists and loves the inclusion of some of his early work in the Davis show. The fire in the show's title is literal — in 1985, one broke out in Henderson's home studio. He was traveling at the time and thought all his paintings had been destroyed. But some survived, and many of the pieces that were covered in of dirt and ash have been restored by the Manetti Shrem.

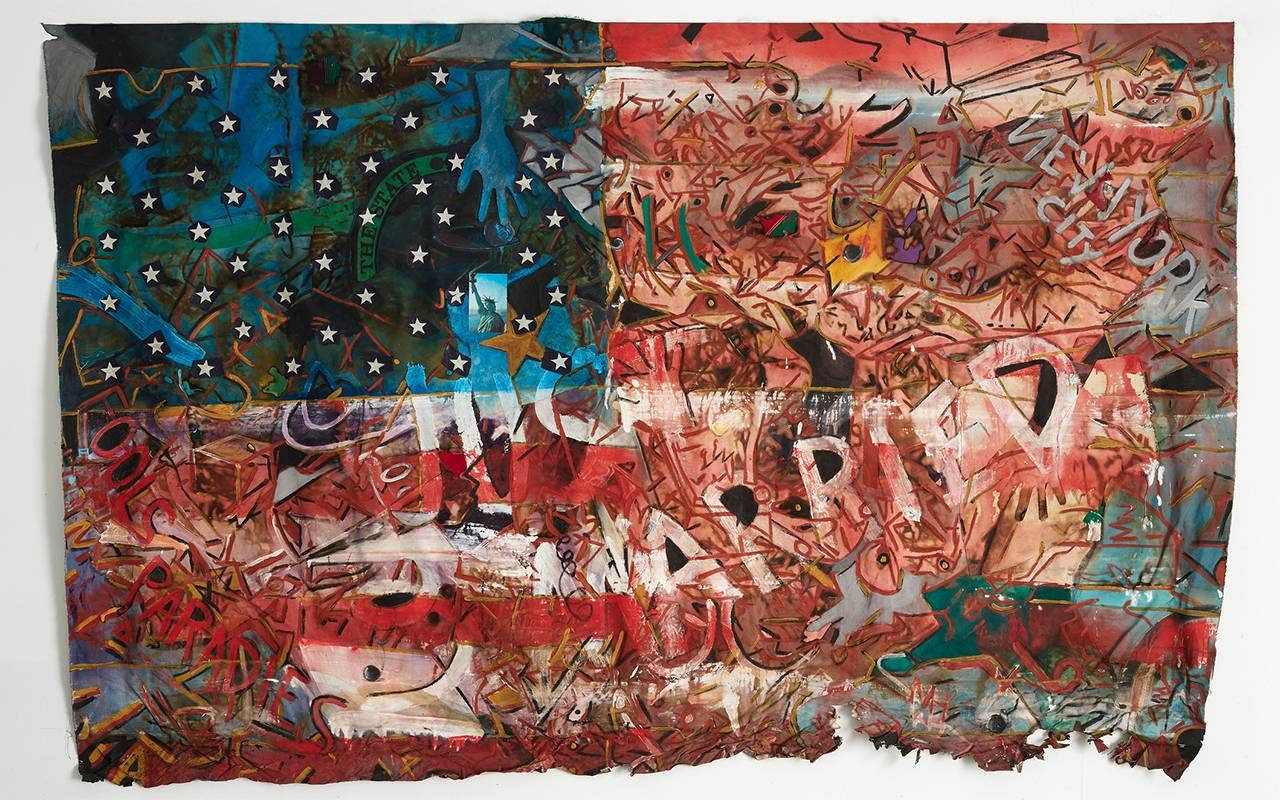

One of the paintings in the exhibition, Love it or Leave it, I Will Love it if You Leave it, was purposefully left unrestored by the curators, Dan Nagel and Sampada Aranke. The painting, the bottom scarred from the fire, depicts a flag covered in what looks like graffiti, and you can make out the word, "marriage," and a small picture of the Statue of Library.

Love it or Leave it, I Will Love it if You Leave it is hung lower than other works in the show. Aranke, a professor at Chicago's School of the Art Institute who specializes in Black art, says she made that decision to make it more accessible to viewers — and to encourage thinking about what the flag symbolizes.

"By placing the flag lower, I am trying to ask the viewer to reflect upon or even question its power — and by extension that of the nation," she wrote in an email. "I also wanted the viewer to be able to see the flag's detail — the intense layers of composition and formal choices as well as the material evidence of the fire."

Other paintings from the Civil Rights era include Freedom, which shows Black prisoners rising against the white prison guards, and Non-Violence (the one the Whitney acquired), depicting a white police officer wearing a swastika armband attacking two Black people with a bloodied knife.

Aranke considers Henderson's work prescient.

"Whether explicit or abstract, Mike's works embody the many layers of systems (police, belief systems, art world gatekeepers) that create almost impossible conditions for Black people to live."

"Whether explicit or abstract, Mike's works embody the many layers of systems (police, belief systems, art world gatekeepers) that create almost impossible conditions for Black people to live," Aranke wrote. "Mike takes those complexities and presents them in both painting and film, using both to unpack the rich nuances of what it means to inherit systems that are beyond one's control."

With the exhibition, Aranke wanted to showcase Henderson's versatility and show his work as part of a history of Black radical critique. She calls his work moving and dynamic.

For his part, Henderson says he loves everything about the exhibition. He wanted to be an artist and he made himself one. And in his decades teaching at Davis, he influenced hundreds of students, such as Carlos F. Jackson, a painter and professor at Davis and Maisha Winn, who also works at Davis, co-directing the Transformative Justice in Education Center.

Henderson says he wants to be an "oracle," there to help young artists the way people inspired him at SFAI. He adds that as a kid, he dreamed of getting a guitar and a box of paints for Christmas. Being at SFAI in the 60s was like that, but better.

"It was like this package waiting to be opened and everything in there was just like, 'Wow, just what you want.'" Henderson said. "It was the perfect gift for me. The right people, the right time."