How a Piece of Shrapnel Changed My Dad's Life

An old photo album introduced me to a sailor at Pearl Harbor: my father

(To commemorate the 75th anniversary of Pearl Harbor, Next Avenue is republishing this 2013 article by the son of a sailor who served on the U.S.S. New Orleans there.)

Shortly before he died, my father showed me something I didn’t know he had. He kept it hidden in a shoebox. Opening the lid, he took out a jagged, baseball-size piece of black metal. It was part of a fragmentation bomb that had exploded alongside his ship at Pearl Harbor on the morning of Dec. 7, 1941. “I was standing on deck,” he told me. “The bomb’s blast knocked me over. This shrapnel went inches over my head.”

Sixteen days shy of his 21st birthday, my father, Clinton Stark, was serving aboard the U.S.S. New Orleans when the Japanese attacked the U.S. fleet. He never spoke to me about what he saw or felt that infamous day. I don’t think he ever shared those feelings with anyone.

In my mother’s 60-plus years of marriage to him, she said she only saw him shed tears on one occasion. It was when they went to Pearl Harbor to visit the U.S.S. Arizona memorial.

But after my father died in 2004 at age 84, I discovered another side of him.

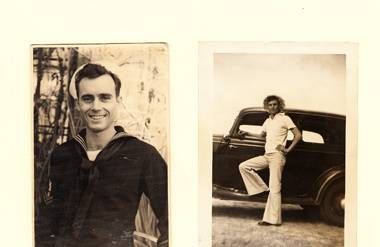

From 1939 to 1941, he kept a photo album of his years stationed in Hawaii.

I took it home with me after my mother died in 2007. It sits on my dining room table. Made of rawhide, the album’s cover says “Cruise Album” on it. Below that is a brightly colored, raised depiction of the New Orleans, a heavy cruiser built at the Brooklyn Navy Yard in 1931.

The album is filled with black-and-white snapshots that my father took with an Eastman Kodak camera, a Folding Hawk-Eyes Model B. I have the camera, which is still in its original box, along with the instruction manual. I keep it on a bookshelf for all to see.

A Childhood That Made Him Tough

My father joined the Navy at the height of the Great Depression. It was his lifeline. Before enlisting he had been living by himself in a desert shack east of Palm Springs. Shortly after his mother died, his father drove off, never to return. At age 13 my father was left to fend for himself. He killed deer and rabbits for food. He wore hand-me-downs from neighbors. At night, he once told me, he read books and shot rats to pass the time.

He didn’t talk much about those years, though. When I was little, I asked him if he cried when his mother died, but he didn’t answer. All I know is he hated lily plants. “They smell like funerals,” he told me.

Along with old photographs, the album contains Christmas cards, newspaper clippings and party invitations. One shipboard holiday menu lists cigarettes among the food items being served. There’s even a program for a boxing tournament between the crews of the New Orleans and another Navy cruiser, the U.S.S. Portland. My father's name is on the bill in a lightweight bout. A newspaper clipping inside the program — titled "New Orleans - Portland Smoker" — shows that the fight ended in a draw. I never knew my father could box.

If nothing else, my father’s childhood taught him how to look out for himself, which this photo album demonstrates.

A Closer Look Inside

Its pages are filled with pictures of him with a 1933 Ford V-8 that he fixed up and restored. He turned it into a taxi, charging his fellow shipmates to take them around Oahu on their liberties.

One photo, captioned “Me, my hat & my car,” shows my father proudly posing alongside the Ford. He’s wearing white Navy bell-bottoms and a white cotton shirt. His right foot rests atop the car’s running board. Atop his wavy black hair is a hat made of palm leaves. Next to that picture are shots of my father driving a group of sightseeing sailors around the island for the day, including one that shows them all sitting alongside the car having a picnic. His buddies' names, written in white pen, are Cactus, Stew, P.A. and Chick.

My father titled one of the pages in the album “Gobs and gals, mostly gals.” It features photographs of mainland women who corresponded with him during the war, including Maxine, Velva, Wallie, Lily and June. One is signed “Love and stuff, Fern.” They all look like the girl next door.

There are pages of photos my father took of the U.S. fleet before the attack. One is captioned “The battle wagons at Pearl Harbor.” He took it from the deck of the New Orleans. You can't read the names on the ships, but I'm assuming they include the U.S.S. Arizona and U.S.S. Missouri. I know he said he saw them sink. Another image depicts a nighttime parade of warships shining their searchlights off Honolulu for everyone to see.

A Celebration of Being Young and Alive

Mostly, though, the album is about being young and having fun. Witness the playful captions: underneath a photograph of him smooching with a young woman, “Anyhow, she was a lot of fun, even if she was kind of homely.” Another, entitled “Tsk Tsk,” shows my father and other sailors swimming nude at a large indoor pool.

There are photos of my father and other servicemen jitterbugging with the local girls at a Honolulu dance hall. The sign on the front door lists the entry fees, “40 cents Gents, 25 cents Ladies.” Other photos show my father in a field of sugar cane petting the water buffalo.

There are numerous images of hula dancers, grass huts, palm trees, outrigger canoes, sandy beaches, volcanic peaks, ukulele players, waterfalls, orchid leis and tropical sunsets.

At 18, he had landed in paradise.

The Album Ends in Blackness

The last third of the album is full of empty, black pages — except for one newspaper article that carries the headline “Heroic Dead Are Buried Here to Volleys and Taps.”

It reads: “Without pomp and ceremony, unsung, 2,500 of America’s finest have been buried during the past eight days with simplest of honors. Day after day with the setting sun a tight-lipped group of six foot marines, clad in olive drab dress uniforms, have raised their rifles and fired three volleys over the dead lying in trenches while the buglers have sounded Taps: ‘Lights out! All quiet. Night has come!’”

It appears that after December 7th, my father put the camera back in its box, never to be used again.

With America at war, the U.S.S. New Orleans left Hawaii to do battle. My father spent the next five years in the Pacific Theater.

A Reunion of Shipmates

I once asked him why he didn’t go to a Pearl Harbor Survivors' event that was taking place at a San Francisco hotel. He told me he had gone to one once but left early. He said it was filled with blusterous men who hadn’t been at Pearl Harbor but claimed they were.

He did, however, attend a reunion of his shipmates in 1995 in Reno, Nev.; 55 other men showed up, according to a group photo. He took the “cruise album” with him to share. There is a typed note in the front of it that says, “You may not remember my name or face, but possibly some may recall the only guy aboard who had a car, a 1933 green Ford. It took a lot of shipmates on trips around the island, to Honolulu, Waikiki and other liberties. If you were one of these, or in one of the pictures, I would like to hear about it.”

I don’t know if he did. I would love to know what happened to the car. I wish I could ask him.

I never did find the shoebox with the shrapnel in it after he died. I searched my parents’ house for it, too. I have no idea what he did with it, or why.

I only know that the album reveals a father I didn’t know existed. He was young, if only briefly. On a beautiful morning, a piece of black metal took that away.