She's Fighting Every Day for Women Released From Prison

A parolee-turned-Purpose Prize winner describes her journey in her book

After two decades of cycling in and out of the criminal justice system and various prison stints, Susan Burton decided to make a change. She found work as a live-in caregiver for an older woman, entered into treatment for drug addiction and started her life over. However, finding support was difficult because her felony record prevented her from qualifying for caregiver licensure, not to mention food stamps, housing assistance and easy employment access.

Burton's own experience prompted her to start a nonprofit organization to help other formerly incarcerated women who were trying to turn their lives around. Originally run out of her apartment for women she met at the bus shelter, she named her organization A New Way of Life and it grew and expanded over the years. In 2012, she won Encore.org's Purpose Prize, which rewarded $100,000 to people over 60 who are truly making a difference in the world.

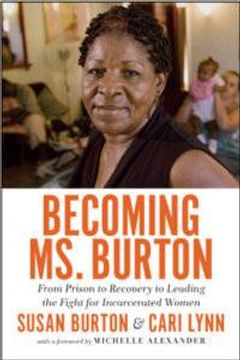

And this month, Burton published her book. This excerpt originally appeared in Becoming Ms. Burton: From Prison to Recovery to Leading the Fight for Incarcerated Women, published by The New Press. Reprinted here with permission:

I hadn’t seen Ingrid in several years when I picked her up in downtown Los Angeles. In her prison-issue clothes, she looked worn and weary, not at all like when she first showed up to my house in 2007, 24 years old and holding the hand of her 5-year-old daughter, Simone.

As Ingrid got in my van, her once-sparkly eyes filled with tears. “I should have called you, Ms. Burton,” she said.

“You did call me,” I said. “That’s why I’m here.”

She shook her head. “Before I was arrested. I wasn’t doing so well. Simone kept telling me to call you, that you would help me. But . . . I felt I’d let you down. I wasn’t working because I had two babies one after the other. I gave up my housing to move in with my new baby’s father. But it was a bad relationship. I was bruised up.” Her voice quivered. “I didn’t want you to see me like that.”

As I listened, I recognized that fierce combination of pride and shame, how such opposite emotions could consume a person, forcing you into thinking you can manage, you can do it all, all by yourself. I drove Ingrid back to my house in Watts, a working-class black community of Los Angeles, immortalized in 1965 by racial tension and police brutality that sparked bloody riots. In a way, Watts was emblematic of so many of its residents. Efforts at revitalization were continuously overshadowed by staid perceptions of violence, gangs and crime. Even in the face of a dramatic and steady decrease in violent crime, Watts still struggled for redemption. To me, this was a community of perseverance.

Nearly 10 years ago, in my two-story, pink stucco bungalow, Ingrid and Simone had thrived, and I’d grown attached to those two. Little Simone, with her mother’s sweet smile, knock-kneed to the point you’d think one leg was gonna trip over the other. Ingrid, with smooth charcoal skin and full lips, her effervescence belying the many lives she’d lived in not so many years. I’d taken Ingrid with me to meetings with policymakers and political activists, discovering what family and teachers should have been nurturing in her all along: she had a sharp mind and an ease with public speaking. I’d watch Ingrid stand before crowds and tell her story.

“I can count the times I saw my mother sober,” she’d begin. “My childhood memories are filled with violence. I can’t remember any happy times, just black. Until one day, my dad came and got me, and I lived with him for a month. He bought me toys and set up an area for me to play. He made me breakfast every morning and took me places, to see family, to get ice cream. I never saw him angry. But he couldn’t keep me because he had a felony record. That was the best month on my life.” She went on to describe years of group homes and boot camp, and eventually escaping to the streets of South Central L.A., selling drugs to get by, giving birth at 19 to Simone, being incarcerated shortly after.

Ingrid’s story pierced me so deeply because she reminded me of my younger self, a strong-willed woman swirling in trauma and tragedy, with so much to offer if only given the chance. She’d tell me, “Every time we go speak, it makes me want to be involved more and more. I can see the bigger picture, and I want to be part of that.”

Now, Ingrid was 34 years old. Her life had changed in a single day, outside a Dollar General store. Having scrounged up the money to buy Pampers and baby formula, she took her screaming toddler with her and made a bottle in the checkout line, but left her sleeping baby in the car, the windows open for air. Not more than 10 minutes later, when she returned to her car, the police were there. She was arrested for child endangerment, though the baby was unharmed. The police impounded the diapers and baby formula in the car, despite Ingrid’s pleas that the children were hungry and needed changing. Because of her history, she was guilty before ever standing trial. She was sentenced to three years in prison and lost custody of all three of her daughters.

I was silent while she blamed everything on herself, how she’d been frazzled and sleep-deprived and, looking back, perhaps had postpartum depression. Okay, I thought, but had Ingrid been a person of means, had she been in a different neighborhood, had she not been black, would she have been sentenced to years in prison? Or would she have been given help, sent to parenting classes and therapy — resources that existed for certain people but not others?

Did I even need to ask the question?

Ingrid’s story could have — should have — been different. Same with my own story, and the stories of most of the 1,000 women and their children who’ve come through the doors of A New Way of Life, seeking safety, productivity, meaning and fulfillment.

So I keep asking questions. Why are black Americans incarcerated at nearly six times the rate of whites? Why are prison sentences for African Americans disproportionately higher? Once released, why do people face a lifetime of discriminatory policies and practices that smother any chance of a better life?

Nearly 20 years ago, before I began looking at the big picture — before I fully recognized there was a big picture—I set out to offer the type of refuge and support I wished I’d had: a house of women helping women. I came at it with only a GED earned in prison, without mentors, without funding. All I had was life experience. All I knew was there had to be a better way.

Now, every year in South L.A., around 100 newly released women and their children call A New Way of Life home. In a state where more than half of all people with a felony conviction will return to prison, our program has a mere 4 percent recidivism rate.

We assist women in completing their education and finding jobs; we help women regain custody of their children; we provide 12-step programs, counseling and peer support groups. All for less than a third of the cost of incarceration. Our annual cost per woman at A New Way of Life is $16,000 — compared to the annual cost of up to $60,000 to incarcerate a woman.

But something bigger than I could ever have imagined happened. As we women began telling our stories and talking about what was going on around us, I found my voice. I could no longer shake my head and helplessly ask the same questions over and over again. It was time to change the answers. To do that meant tackling the many institutional barriers — the laws, policies and attitudes — that created mass incarceration and that continue to punish people long after they’ve served time.

The 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution abolished slavery other than in prisons — but it was a lie that you regained your freedom once you left the prison gates. Upon release and for the rest of your life, you faced a massive wall of No. The American Bar Association documented 45,000 legal sanctions and restrictions imposed upon people with criminal records, a near-impenetrable barrier denying access to employment, student loans, housing, public assistance, custody of your children, the right to vote — in many places, the formerly incarcerated are even blocked from visiting a loved one in prison.

The minute I picked up a supposedly free Ingrid, these collateral consequences stared her square in the face. The highest priority was to get her kids back. But before she could even attempt to regain custody of her daughters, we had to get her set up in permanent housing. But she had to have money to cover rent, so first we had to find her employment. Of course only a limited number of jobs existed for someone with a conviction. Are you starting to get the picture? By design, Ingrid’s hopes and dreams were all but snuffed out, and her children’s lives thrown into permanent disarray, that day she made a faulty decision outside the Dollar General store.

This isn’t a problem that’s going to go away all on its own. The United States has the largest prison population in the world, and most of those prisoners will one day be released. I realized that formerly incarcerated people had no voice, and no one seemed willing to speak for us. As I built A New Way of Life, it sometimes felt as though a new underground railroad was taking shape. We, the people of the com- munity, weren’t going to let each other fall. We would rescue each other, and deliver people to a lasting freedom. We would do all we could so that women like Ingrid could get their lives back, and make better lives for their children.

Through the network I’d cultivated over the past two decades, we began chipping away at what was once nearly impossible. We found Ingrid a job doing intake at a women’s homeless shelter. Working closely with the Department of Children and Family Services, and with proof of her residence at A New Way of Life, Ingrid was approved to have her children on weekends while she pursued the longer process of regaining full custody. She was putting money into a savings account, and working with housing agencies to find a permanent residence.

“Ms. Burton,” she said, the sparkle having returned to her eyes, “I’m moving my life along.”

This excerpt originally appeared in Becoming Ms. Burton: From Prison to Recovery to Leading the Fight for Incarcerated Women, published by The New Press. Reprinted here with permission. You can purchase the book online at New Press or various other book sellers.