New Studies Find 9/11 First Responders May Have Increased Dementia Risk

Research points to PTSD and Ground Zero toxic dust as contributing factors

Americans promised to “never forget” Sept. 11, 2001 — that tragic day when the deadliest terrorist attacks on the nation’s soil saw 3,000 lose their lives in New York City, at the Pentagon and in a field in Shanksville, Pa. Nineteen years later, it may be the first responders and rescue/recovery workers at the World Trade Center (WTC) that day who are now at risk of forgetting.

Two studies conducted by researchers at the Stony Brook University World Trade Center Health Program and presented at the recent Alzheimer’s Association International Conference examined 9/11 first responders who cleared the 1.8 million tons of Twin Tower wreckage debris searching for human remains. These responders inhaled a daily toxic cocktail of chemicals and particles, including asbestos, benzene, fiberglass and mercury.

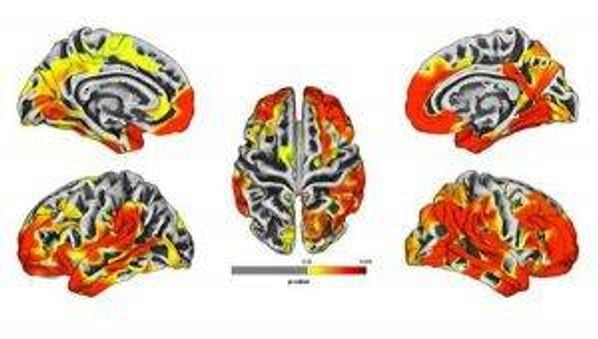

The studies show brain scans and blood biomarkers consistent with changes in the brain similar to early-stage dementia and Alzheimer’s. Both looked at first responders who reported some cognitive impairment and show that the findings may be linked to chronic post-traumatic stress disorder (PSTD) and chronic exposure to toxic dust pollutants.

“What brings these responders into the clinic is not memory loss, it is depression or aggression which are other symptoms of Alzheimer’s."

One study, the first to use neuroimaging to look at PTSD and the development of mild dementia, analyzed brain imaging scans of first responders ages 45 to 65, both with and without any symptoms of cognitive decline. Researchers found the thinning of the gray matter in the brain scans was indicative of early stage dementia, but the parts of the brain affected did not match known diseases. These results build on previous work in this population noting that cognitive impairment occurs at about twice the rate of population controls for people 10 to 20 years older. Given these first responders’ average age of 53, their brains appeared more than 10 years older than that.

Researching the Health of World Trade Center First Responders

The second study analyzed 276 proteins in the blood of WTC responders with an average age of 55 who also reported PTSD and cognitive impairment. Researchers found changes in the blood consistent with both PTSD and conditions of dementia.

“The chronic nature of these first responders who have re-experiencing symptoms of PTSD or spent more time in the toxic dust show the health impact of 9/11 takes a long time to emerge,” said Sean Clouston, lead author on the studies and associate professor of family, population and preventive medicine at the Renaissance School of Medicine at Stony Brook University.

Clouston has been researching WTC first responders and cognitive impairment, PTSD and toxic pollutants for five years. He says now that most of these responders are in their 50s or older, continued investigation might reveal growing concerns for early dementia risk. Up until now, the first responder health impacts have been mostly respiratory, gastrointestinal, psychological or cancer.

“What brings these responders into the clinic is not memory loss. It is depression or aggression, which are other symptoms of Alzheimer’s,” said Clouston. “Right now, PTSD is one of the certified health issues under the World Trade Center Health Program, but cognitive impairment and dementia are not.” The federal World Trade Center Health Program provides free medical and mental health services to first responders and survivors of the 9/11 attacks.

A Wife Remembers for a Husband Who Cannot

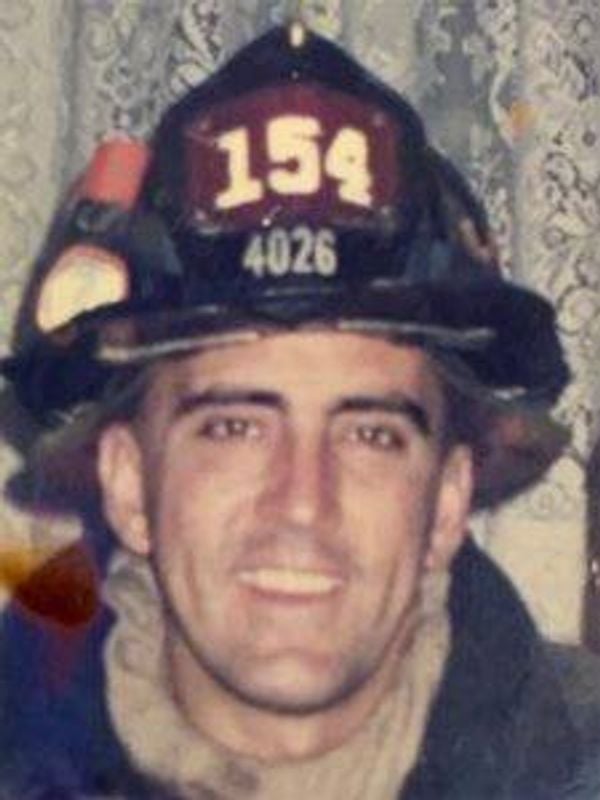

Dawn Kircher remembers the morning of Sept. 11, 2001 like it was yesterday. Her husband Ronnie, 39 at the time, had just finished a late night shift at Ladder 154, the fire station in Jackson Heights, Queens. The minute the second plane hit the South Tower of the World Trade Center, Ronnie called Dawn to tell her he was headed into Manhattan to volunteer to help. Over the next six months, Ronnie spent more than 600 hours working 12-hour shifts on “The Pile,” the name first responders and rescue workers (firefighters, law enforcement, steelworkers, construction teams, electricians and plumbers) gave to the toxic debris wasteland known as Ground Zero in lower Manhattan.

“I was managing a five-year-old son and an infant daughter and Ronnie never shared a lot of details of his exhaustive work, so I never really worried about him. Growing up in New York City he was doing what he always dreamed of: being a firefighter,” Dawn explained.

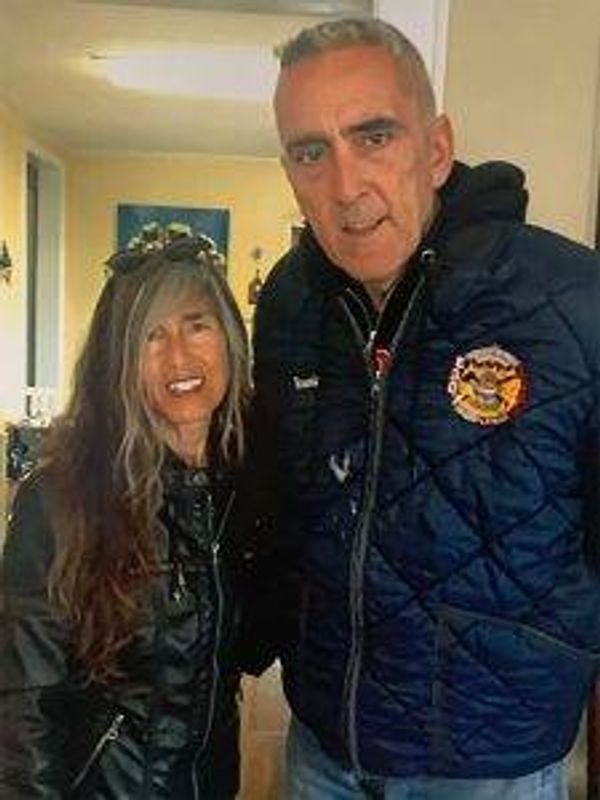

Almost two decades later, at 58, her sharp, quick-thinking, healthy husband who never drank or smoked is unable to have a conversation. “His words just come out as jibberish,” said Dawn.

Dawn’s first signs of concern came when Ronnie was 51. He started to forget how to do everyday tasks such as putting toothpaste on his toothbrush, using the lawnmower and driving. He’d always been a neat freak, but now the garage was terribly cluttered. Over the last three years, his cognitive decline has been swift.

"There is no doubt in my mind that six months on ‘The Pile’ helped accelerate his lung problems and his neurological problems.”

Now, Dawn is a 24/7 caregiver for her husband. “He has seizures and has lost his coordination to do everyday tasks. If I ask him to lift his foot so I can help him put on his shoes, he doesn’t understand the request,” she said.

After a series of cognitive tests and brain scans, a neurologist told Dawn, “Your fifty-one-year-old husband’s brain shows the atrophy of a cognitively impaired eighty-five-year-old.”

Among the current WTC Health Program members, 17,665 have mental health issues such as PTSD and 41% of those are 55 to 64. This is more than twice the percentage of the general population over 55 with mental health conditions, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

As a WTC Health Program member, Ronnie retired from the fire department in 2009 with certified health issues of asthma and COPD related to 9/11. He has been part of Clouston’s monitoring and research studies at the Stony Brook University World Trade Center Health Program, which operates two clinics in the Long Island area.

“I don’t believe Ronnie has PTSD, but there is no doubt in my mind that six months on ‘The Pile’ helped accelerate his lung problems and his neurological problems,” said Dawn.

How These Studies May Point to Alzheimer’s Risk for Older Americans

The implications of these studies on 9/11 first responders may point to important Alzheimer’s risk factors for the general public.

According to the American Psychological Association (APA), PTSDaffects more than 8 million Americans each year and 1 in 11 people will be diagnosed with PTSD in their lifetime.

Survivors of the Holocaust and military veterans are who we often think of when we hear about PTSD, but natural disasters, violent assaults, domestic abuse, car accidents and terrorism can all trigger PTSD episodes. One recent study found that PTSD may actually be a side effect of the COVID-19 pandemic.

According to the APA, women are twice as likely as men to have PTSD. Latinos, African Americans and American Indians have higher rates of PTSD than non-Latino whites.

And numerous studies point to air pollution as a risk factor. One research study found a 138% increased risk of Alzheimer’s in those 65 or older who had breathed in chronic air pollutants that are associated with living close to congested highways.

Never Forget

Of the more than 250 nonprofit organizations created to help those affected by 9/11, few remain due to lack of funding. Among them are VOICES of September 11, New York Says Thank You and Windows of Hope Family Relief Fund, which are dedicated to helping survivors, first responders and families and children of those who died with mental health screenings, financial aid, health insurance, education, support programs and more.

For full-time caregiver Dawn, her self-care is practicing her strong faith and finding “joy every day Ronnie and I are together.” The couple take daily walks, enjoy road trips and find that music bridges the gap in Ronnie’s inability to communicate, “He comes alive with the music,” said Dawn.

She remains proud of her husband and knows he always believed in helping others without thinking of the cost to himself.

“If he had the choice, he’d do exactly the same thing all over again,” said Dawn.

Sherri Snelling is a corporate gerontologist, speaker, and consultant in aging and caregiving. She is the author of “Me Time Monday – The Weekly Wellness Plan to Find Balance and Joy for a Busy Life” and host of the "Caregiving Club On Air" podcast. Read More