A D-Day Without Vin Scully

The Dodgers’ Hall of Fame broadcaster is no longer with us to tell World War II stories, but we can learn about his experience in the Navy

The late Dodgers announcer Vin Scully rarely spoke of his tour in the U.S. Navy during World War II. In the booth he deflected high praises for his service, saying, "Ah, I did very little."

Instead, the Hall of Fame broadcaster focused fans' attention on active-duty military protecting our interests around the world, and shared stories about veterans to pay tribute to those who gave their lives for our freedoms.

D-Day had special meaning to Scully. Every year on June 6, he shared stories about the Allied invasion of Normandy, France, to make sure listeners and viewers understood the momentous historical importance of that late Spring day in 1944, and why it should be remembered today.

Sacrifice and Valor

In lyrical storytelling form, one of Scully's most sentimental D-Day broadcasts took place on June 6, 2015, when he told stories about the invasion, code-named Operation Overlord, throughout a Dodgers-Cardinals game.

As a member of the greatest generation, Scully was one of the very last broadcasters to serve in World War II.

"It included over 5,000 ships, 11,000 airplanes, 150,000 servicemen and it came down to this. The boat ramp goes down, you jump, swim, run and crawl to the cliffs," he said. "Many of the first young men were not yet 20 years old, and they entered the surf carrying 80 pounds of equipment. Many of them drowned. They faced over 200 yards of beach before reaching the first natural feature offering any protection at all," he noted.

Displaying his love of literature, Scully added a twist to the history lesson for young fans, sharing an anecdote about Army sergeant and author J.D. Salinger, who carried the first six chapters of the classic American novel "The Catcher in the Rye" in his knapsack when a landing craft deposited him on a blood-soaked beach, code named Utah.

He Served, but When?

As a member of the greatest generation, and a younger contemporary of Salinger's, Scully was one of the very last broadcasters to serve in World War II. When he died in August 2022 at age 94, the Transistor Kid, as he was nicknamed, was eulogized worldwide on television networks, radios, magazines and newspapers.

Yet the dates of his military service were inconsistent. Seeking answers, I turned to an independent firm, Redbird Research, to look for information about Scully at the National Military Personnel Records Center office in St. Louis, Missouri. When his 50-page military file arrived on my doorstep several weeks later in a red, white and blue Priority Mail envelope, a revealing chapter in the then-teenaged broadcaster's life came into focus.

Vincent Edward Scully served in the U.S. Navy from August 17, 1945, several days after the Japanese agreed to surrender, to July 19, 1946.

According to Scully's military personnel file, he enlisted at age 17 in the Navy V-6 program as an Apprentice Seaman at the U.S. Navy Recruiting station on Madison Avenue in Midtown Manhattan. At the time, he lived at 869 West 180th Street and Navy officers had to trek uptown to witness his mother, Bridget "Bridie" Reeve, sign a permission form allowing her only son to enter the service.

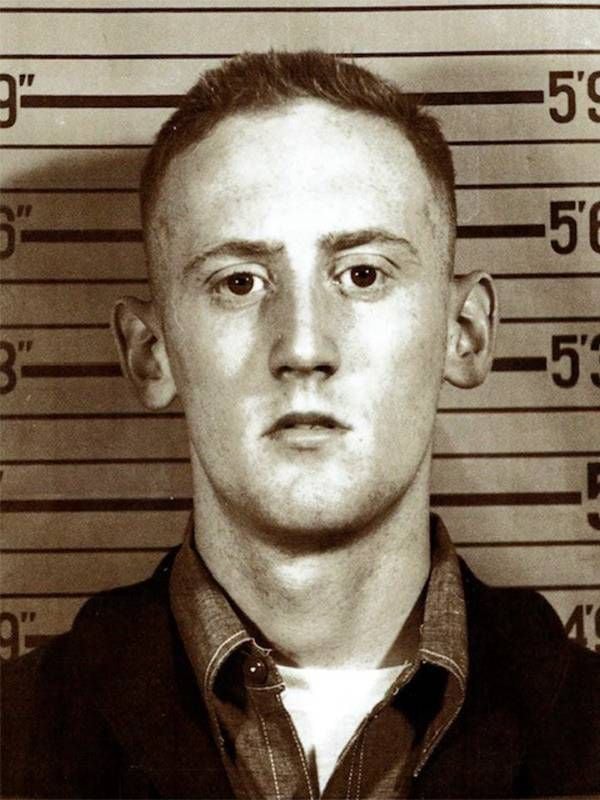

The Seaman's file photo looks a bit like a mugshot of the square-jawed 139-pound auburn-haired boy in a dungaree shirt with a buzzcut and freckles. A Sports Illustrated feature once called Scully, a smidgen over 5 foot 9 inches tall, "a good field no-hit outfielder" as a sophomore on Fordham University's team.

Though he was just a kid, with a knobby Adams apple who barely shaved, Scully knew exactly what he wanted to do with his life. When he left the Navy, his Notice of Separation form said he hoped to become a "Journalist" in "Radio Announcing in New York."

Journey from Coast to Coast

Scully's dream of becoming a broadcaster began as a kid, where he listened to ball games on the tabletop radio and became a fan of the New York Giants. During the war, Scully was exposed to California and the people who later would shape his destiny as a bi-coastal broadcaster with the Dodgers.

Scully reported for active duty on October 23, 1945. The next day the Navy shipped him off to boot camp for 10 weeks at Camp Peary, a legendarily humid pine-forested, mosquito-infested training base on the banks of the York River near Williamsburg, Virginia. Documents show that he reported to CSK (Chief Storekeeper) Manley in Room 2022 of the Arlington Annex.

"A very kind person who knew everything about baseball."

"Swamp Peary" as it was called housed thousands of German POWs during the war, including detainees from captured U-boats. The base was also a training station for the Navy's Construction Battalions, better known as Seabees, and home of the illustrious Camp Peary Pirates sports teams that played some of the fiercest baseball, football and basketball in the service.

From Virginia, a stronger, faster, more regimented Scully headed to U.S. Naval barracks in Washington, D.C., for transportation school for two weeks. On January 5, 1946, he transferred to Naval Barracks, Tower Hall, 820 North Michigan Avenue in Chicago for temporary duty under instruction at the Inter-territorial Military Committee Office. His commanding officer was Capt. H.W. Underwood, USN, Ret.

During the transit from Chicago to a new duty assignment in California, Scully was placed in charge of John Layfield Mathison and Leon Emile DeMulder, who passed away at age 92 in 2020 in Silver Spring, Maryland.

DeMulder's son Mark said in a Facebook conversation that his father did not keep up with Scully after the war but described the future Hall of Fame broadcaster as a "a very kind person who knew everything about baseball."

A California Idyll

Though Scully maintained a 4.0 in military conduct his training was not a breeze and he faced challenges that may have been blessings in disguise. Like many of his peers in the service, Scully failed the "Eddy Test," a notoriously difficult test used to identify candidates with an aptitude to become Navy radar technicians.

Scully's ultimate destination was the 12th Naval District in San Francisco for "duty in Passenger Transportation Office or such duty as the Commandant may assign." His seven-month stint in California opened his eyes to fun-filled exploration where he enjoyed the sunshine, sights and pretty girls along the Pacific coast.

On May 20, 1946, the Navy granted Scully 23 days of leave. After a quick trip home in the belly of a train filled with service members, he hit the road to tour California.

"Can you imagine that? Inviting a couple of strangers off the street for dinner?"

Years later, Scully described that break to Sports Illustrated."When I was in the Navy I was stationed in San Francisco for a time, and I came down to Los Angeles on liberty to meet a friend who was a marine at Camp Pendleton," he said.

"We were wandering around Hollywood one Sunday morning when a girl stopped in a car and asked us if we'd like to come to her parents' house for Sunday dinner. We said sure. Can you imagine that? Inviting a couple of strangers off the street for dinner?

"It was great — nice dinner, nice family, a very nice house," he continued. "That evening the girl drove us back to Hollywood and dropped us off where she had found us. But I asked her, 'Where were we today? What's it called?' And she said, 'Brentwood.'"

Dodgers fans know that the affluent Brentwood section of Los Angeles would become Scully's home after the team decided in 1957 to leave Brooklyn for L.A.

A Sailor Can Dream, Can't He?

Scully mustered out of the service on July 19, 1946, with the rank of Seaman First Class.

When the broadcaster passed through the gates of Camp Shoemaker east of San Francisco with a duffle slung over his shoulder, he did not rush back home to New York. Instead, he took a job at the White Log Coffee Shop, a popular 24-hour restaurant chain with the slogan "Your welcome is not measured by the amount you spend." Those words aptly described Scully's character, and the way he treated people for the rest of his life.

Scully's military file contains a letter written by Carl Groh, manager of the log-cabin style restaurant at Mason and O'Farrell streets in San Francisco, who verified his employment.

Natural-Born Chatterer

In the 1940s, coffee shop waiters wore white hats and uniforms with aprons. They washed dishes, bussed tables and grilled up pancakes and burgers for war-weary Americans.

As Scully poured coffee and served orange juice, he also talked sports with customers. That casual, unpretentious relationship with people from all walks of life never changed during his career with the Dodgers.

Other Greatest Generation veterans had that same ability to connect with the public.

Ronald Reagan, who lived in the Pacific Palisades section of Los Angeles, not far from Brentwood, called Scully "a great sportscaster . . . and a darn good friend,'" according to Curt Smith, author of the sportscaster's biography, "Pull Up a Chair: The Vin Scully Story."

Due to poor eyesight, Reagan, like Scully, served stateside: in his case, making military training films, Smith said. Like most veterans, both underplayed their contributions to the war effort. But, Smith adds, "Each was an artist behind the mic."

Two of Scully's friends are still with us. Fordham Prep pal Lawrence "Irish" Miggins, 97, of Houston, was a Merchant Marine in the war and then an outfielder and first baseman for the Cardinals. Carl Erskine, 96, served in the Navy and then signed with the Dodgers after the war; the author Roger Kahn immortalized Erskine as "Oisk" in his best-selling elegy to the 1950s Dodgers, "The Boys of Summer." Erskine was one of Scully's closest friends and penned this limerick after an emotional visit to Normandy:

The Sacrifice

Can we total the debt that we owe

To so many whom we will never know?

Each life sacrificed

In a way was like Christ

We are free because they took the blow.

Editor’s note: Roughly a dozen major leaguers who served in World War II survive today (Baseball Almanac keeps a list). They include the oldest-living players, Bay Area resident Arthur “Art” Schallock, 99, a former left-handed pitcher for the New York Yankees and the Baltimore Orioles who served as a naval radio operator aboard the aircraft carrier USS Coral Sea, and Rev. Dr. William Henry Greason, 98, a Montford Point Marine and Congressional Gold Medal recipient who fought in the Battle of Iwo Jima and re-enlisted to serve in the Korean War. Greason in 1954 became the first African-American pitcher for the St. Louis Cardinals and he is one of the last living men to have played in the Negro League.