Under the Big Top: My Great-Grandmother's Life in the Circus

Her memorabilia, which eased my difficult childhood, is now healing my grief as I mourn my mother

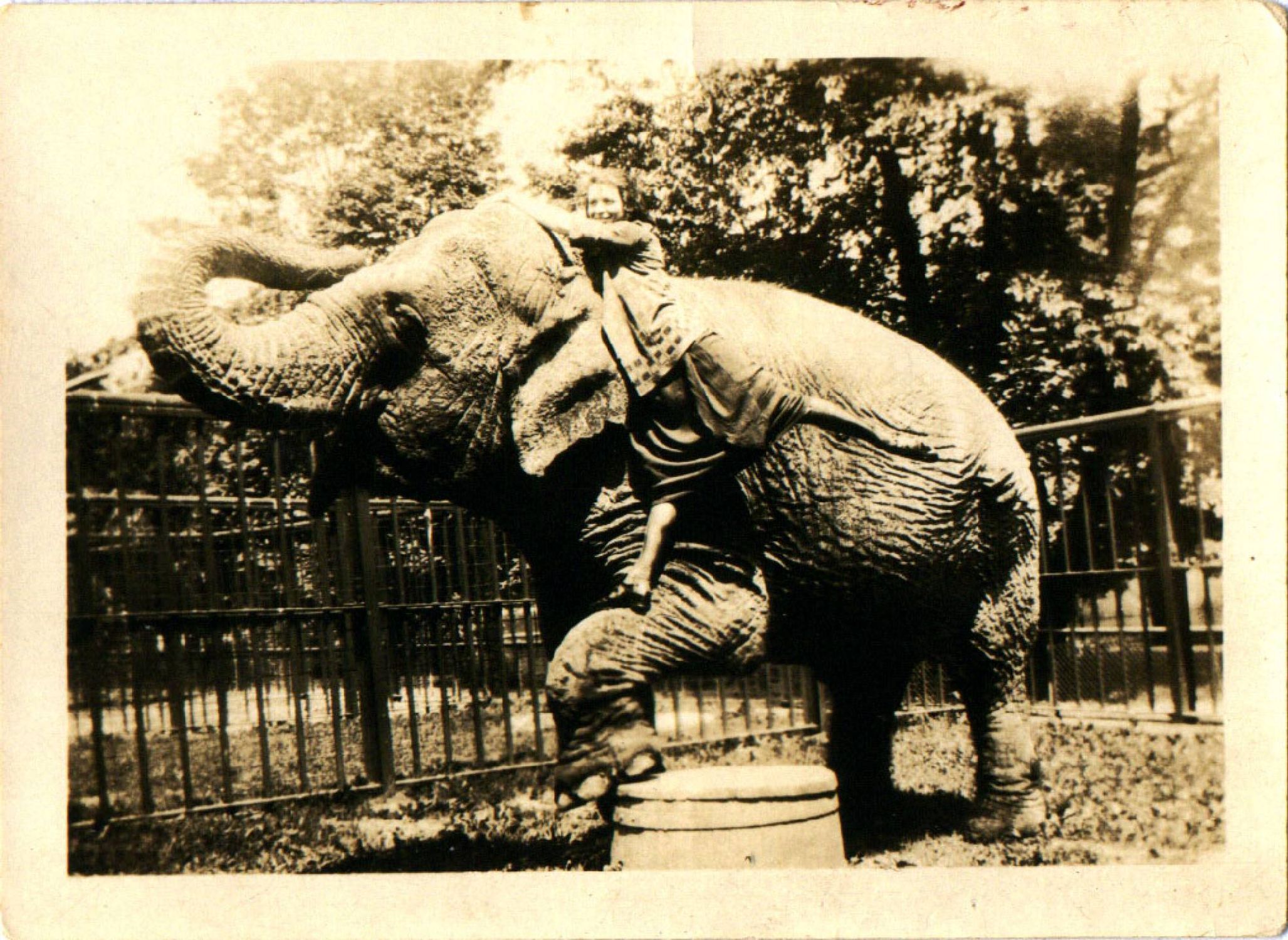

Self-care isn't supposed to look like squinting at a century-old photograph of your great-grandma pirouetting on the bent knee of an elephant under an oak tree, but there it is. Instead of yoga practice and home mani-pedis during the pandemic, I spent hours hunched over on my bedroom carpet, organizing hundreds of scallop-edged black and white photos from my great-grandparents' days in the circus and vaudeville.

I became the family historian by default after my mother died recently, and her wife discovered three suitcases full of pictures and newspaper clippings and promotional posters, and mailed them my way.

My sister finds our bizarre showbiz ancestors irrelevant to her elegant lifestyle. My brother has Down syndrome; he only has eyes for his GQ subscription. Without our mother to ground us, we've spun apart, flung into separate parts of the country in our centrifugal grief.

My sister got the family silver; I inherited my great-grandfather's juggling pins and the leather cap he built to balance upside down on a rigging 20 feet in the air. I'd been coveting that cap for decades.

I grew up hearing about how — as a teen — he ran away from his father's sanitarium to join Howe's Great London Circus. There, he met my great-grandmother who'd left the family farm in Missouri to become a bareback rider. They didn't fall in love. They didn't even like each other.

She was Hap's straight man, eye candy who handed up his juggling pins while he cracked wise on the wire.

But they shared a ferocious ambition and a kindred comedic timing, so they married and put together a juggling and wire-walking act, billing themselves as "Hap Hazard, the careless comedian, and Mary Hart, who cares less."

Promo photos from the 1920s show her in Mary Pickford ringlets and a tiny black dress, cradling a saxophone below a wire stretched six feet high across the stage. Above her, Hap balances on one foot, a grin lighting up his long face. They're at the start of their career — a career that spanned decades and continents.

As an octogenarian, Mary loved to extract a map from the bag affixed to her walker and point at the places in which they'd performed. "We toured all over the states," she'd tell me. "And Italy and France and Germany." She'd pull out a curated selection of photos to illustrate whatever anecdote she'd been rehearsing that morning.

Boxes of Photos From Their Vaudeville Careers

The images became more glamorous when she and Hap became vaudeville performers. Eight-by-eleven glossies show her in sequined dresses with perfectly-curled bangs and perfectly-lined lips and brows.

She was Hap's straight man, eye candy who set up his jokes and handed up his juggling pins while he cracked wise on the wire. They bought a two-passenger plane and painted his name on the wings; when they traveled to a new city, he flew the plane upside down so people below could read the words "Hap Hazard." No hashtag needed.

I have photos of their plane, and pictures from their vaudeville career and their U.S.O. camp shows. I have a recording of the act they performed on the county fair circuit in the 1950s. A few of these images might interest a museum professional who'd store them with thousands of others in a basement file. But what do I do with the rest?

Professional photo organizers charge big bucks to deal with boxes of images such as mine, to digitize and categorize and otherwise preserve a century of history. I don't have the money for this. What I have is time.

Mary and Hap weren't celebrities. They never received top-billing. Even when they toured overseas during World War II, they were middle-of-the-marquee warm-ups to headliners like Fred Astaire. How can I justify spending night after night with this legacy of photos bequeathed to my disinterested grandmother and then to my less-enthusiastic mother until they finally arrived en masse on my porch? Who would know — who would care — if I tossed the pile?

The Turmoil of My Family Life

I'd care, desperately. I've been intimately acquainted with these images for decades, with the juggling pins and promo posters, with my great-grandmother and that elephant, my great-grandfather on the wire. These artifacts — relics of my own history — centered and saved me as a child.

In 1979, I lost my mother once before I lost her forever — when I was nine and she left my abusive father and came out as a lesbian. In that homophobic era only six years after psychiatrists reclassified homosexuality as a "sexual orientation disturbance" rather than mental illness, my father sued for full custody of my siblings and me and won.

The judge allowed us to visit her every other weekend, plus a month in summer. On those longer visits, she drove us up to my great-grandmother's house in Monterey. Hap was gone by then, but Mary held forth at her kitchen table.

She told me stories of learning to walk the wire on a rope stretched out between pig troughs, and described how Hap landed their plane in a herd of cows outside Kansas City. She recounted how they sailed across the Atlantic with their juggling act and a set of incredibly clean, incredibly unfunny jokes. (The best of the bunch: "Hey, Mary! Your hen's so mean that she lays deviled eggs.")

I come from big-hearted, hilarious circus people, I told myself as a teen.

In those rare hours, I sat surrounded by my maternal family — Mary, my grandmother, my aunt and uncle, my siblings and my beloved mother — and the sense of safety and belonging overwhelmed me.

I disappeared into Mary's room with its dressers full of memorabilia and went through each methodically, studying the clippings and promotional posters and the scallop-edged testimonials to a lineage that was all indisputably mine.

Kids are more resilient —happier, even — when they have a solid sense of their family history. In the midst of homophobia and hatred in my father's house, I held onto the memory of my great-grandfather's notebooks full of penciled jokes tucked in among Mary's photos of her friends: the Spanish wire-walkers and Chinese acrobats and some guy who balanced his lapdog on one finger.

I come from big-hearted, hilarious circus people, I told myself as a teen. It's the same mantra I recite now through fresh grief, middle-aged and motherless once more, but buoyed by the tangible representation of my relatives spread out on the floor around me.

And so, I'll take the time to digitize and slip hundreds of photos into envelopes labeled "Hap & Mary," "Vaudeville Friends" and "Unidentified Weird Circus People."

I'll research the different performers and how they fit into my great-grandparents' lives. While I'm at it, I'll meditate on how they fit into my life, providing comfort and light in the darkness

Melissa Hart is the author of “Better with Books: 500 Diverse Books to Ignite Empathy and Encourage Self-Acceptance in Tweens and Teens.” She lives in Eugene, Oregon. Read More