Deaf Caregivers Say Fixing Communication Barriers in Health Care Is Long Overdue

As more deaf adults become caregivers to their parents, the need for clear communication with health pros is growing

It was a fall in the middle of the night in 2012 when my mother's life shifted. She had been suffering from arthritis for many years and when she fell, she was rendered immobile. I was living with her at the time, with my younger brother. As we headed to the hospital, I could sense my life changing. I would need to become my mother's caregiver now. What I didn't realize is that I would face my first test in the emergency room.

In the ER that night, I couldn't make sense of the flurry of nurses and doctors' voices surrounding me and couldn't decipher what the doctor on duty was saying to my mother. She can hear; I cannot. (I'm congenitally deaf.) I speak and wear hearing aids, but they were useless in the noisy hospital.

Not knowing what was being said was a huge disadvantage to me. I was so flustered, it didn't occur to me to request an American Sign Language (ASL) interpreter. But even if I had, there's a good chance one wouldn't have been available on short notice. This is a common problem that deaf people face in emergency situations and the health care system needs to fix it.

As the aging population grows, the number of deaf adults caring for their parents is only expected to increase. About 1 in 7 adults in the U.S. aged 65 and older are deaf. An estimated two to three children out of 1,000 are born deaf. In the U.S. and Canada, about 500,000 deaf people use ASL as their primary language.

Requests for ASL Interpreters That Are Denied or Ignored

It's no secret that many people in the deaf community believe the health care system still operates in the Dark Ages when it comes to meeting their needs. Health care information provided verbally is frustratingly inaccessible for many deaf people for whom ASL is their primary language.

"Her husband died [and] she was very traumatized. Not only because of losing her husband but it was also the language deprivation at the hospital."

Being thrust into a chaotic setting without a communication option can leave a deaf person feeling vulnerable and traumatized.

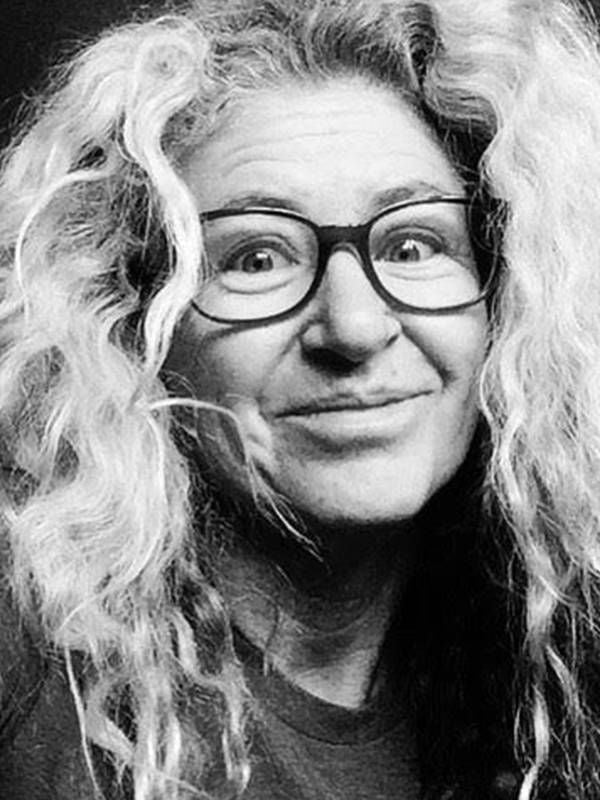

Missy Keast, 54, is a profoundly deaf ASL instructor who lives in Scottsdale, Ariz. and is president of the Arizona Association of the Deaf. She recalls an encounter with a doctor who had no clue how to communicate with her.

"I have eye problems, and I once had to see a specialist," says Keast. When she booked her appointment, she requested an ASL interpreter be present at her exam. "I even called them two or three times to make sure they would provide the interpreter," she says, because, in her experience, an interpreter usually shows up only half the time.

On the day of Keast's eye exam, the interpreter didn't show up and her doctor wasn't helpful. "He refused to write [down what he was saying]," she says. When she asked again for an interpreter, she says the doctor refused. "So, I walked away," Keast says.

Her eye problems continue, but Keast was so bothered by her medical experience that she hasn't yet made a new appointment.

For deaf caregivers, Keast says, mistreatment by medical staff can be even worse than for deaf patients. Keast spoke of a deaf woman whose husband became seriously ill. In the hospital, the woman stayed by her husband's side, with doctors and nurses mumbling at her and refusing to communicate with her via pen and paper.

"She then requested an interpreter and for some reason, they never provided an interpreter [for her]," says Keast. "Her husband died [and] she was very traumatized. Not only because of losing her husband, but it was also the language deprivation at the hospital," she adds.

Under Title III of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), hospitals, clinics and other medical centers are required to provide effective communication to patients who are deaf and hard of hearing. When a deaf person schedules a doctor's appointment, an interpreter must be provided if it's requested before the appointment.

A deaf caregiver can also request an interpreter because the hearing patient can't (and shouldn't) be expected to interpret for the caregiver. But in practice, health care providers often deny or ignore these requirements.

Don’t Go It Alone

Encountering communication problems at every turn is exhausting and deaf caregivers can't be expected to fix the situation on their own. Organizations that provide respite services for caregivers could do a better job, too.

Kay Vincent, 67, was caregiver to her mother, Beatrice, for 15 years. Vincent, who lives in Encinitas, Calif., is deaf and so was her mother. She says it was hard to find in-home care for her mom because there were very few agencies who had ASL-proficient employees. So, when she needed to recharge, Vincent had to turn to her three sisters.

"They came and stayed with her (mother) while I took off on vacations and breaks," says Vincent.

"A lot of doctors ask dumb questions of deaf people."

Vincent also cared for her husband, Jim, who became ill in 2015. His ALS diagnosis forced her to reassess Beatrice's care. She and her sisters agreed Beatrice would move to another sister's home.

Vincent eventually had to quit her job to care for Jim full-time. Her husband died in August 2017.

Juliette Moore, 66, who is deaf in her left ear, sought out help from her brother when caregiving responsibilities for their mother, Florence, increased.

As their mother's health deteriorated in 2016, she became more dependent on Moore, who lives in Pittsburg, Calif. So, her brother set up an alert system that could be triggered by Florence when she needed Moore's assistance.

"My brother made a homemade vibrator system, which allowed me to put the device under my pillow so it would wake me," Moore said. She says it extended the time she was able to care for her mother at home. Florence died in late 2020.

Breaking Down the Barriers for Deaf Caregivers

Solving the many persistent communication problems deaf caregivers face and providing appropriate respite opportunities aren't all that could be done to fix health care access for deaf and hard of hearing people.

More sensitivity training is also crucial.

"A lot of doctors ask dumb questions of deaf people," says Keast. She has been asked if she can read or write, if she lives with her parents and how she knows if she has received an email.

She thinks the misconceptions go hand in hand with doctors not learning enough about their deaf and hard of hearing patients. Keast says more culturally appropriate medical training should be required. And she thinks it should be taught or informed by deaf people. Researchers also need to include the deaf community in more health studies that focus on their unique needs, Keast says.

Fixing communication barriers in health care settings is crucial because misunderstandings can harm patient outcomes, increase health care costs and needlessly traumatize people.

It's been eight years since that visit to the ER with my mother and I still worry about effectively communicating with doctors.