An Early-Onset Alzheimer's Diagnosis Is Met With Resilience

Brian Van Buren also gets a little help from some high-tech friends

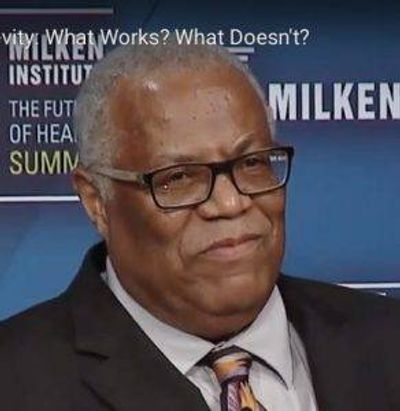

When I phoned Brian Van Buren at his home in Charlotte, N.C., to discuss his diagnosis of early-onset Alzheimer’s for our scheduled interview at 4 p.m., he answered on the first ring.

“You’re right on time!” he said, cheerfully. “I just finished my all-day online conference with the Alzheimer’s Association,” he said.

Knowing how draining a long day of meetings can be, I feared he might be too wiped out to talk much. But as our conversation stretched beyond 5 p.m., we were just getting started.

Van Buren, 69, had so many more stories to tell.

“We’d land in Los Angeles, and I’d announce, ‘Welcome to New York!'"

Van Buren’s life has been filled with thrilling adventures. In the late 1980s, he met Princess Diana at one of her pet projects, the London Lighthouse AIDS Clinic, while caring for his late husband (who died before Van Buren's diagnosis); during his 22-year tenure as a flight attendant for United Airlines, he visited 57 countries; he twice appeared on the Oprah Winfrey show, as a survivor of childhood sexual assault by a priest; he raised his voice and marched for equal rights, gay rights and AIDS awareness.

Early Signs of Dementia

The warning signs of early-onset Alzheimer's, subtle in the beginning, came when Van Buren was in his 50s. He dismissed them as “the normal age-related stuff.” Van Buren forgot where he left his keys, got lost driving familiar routes and missed important appointments.

The memory loss and confusion became harder to ignore when, working as a flight attendant, Van Buren could not remember the inflight passenger safety announcements he had repeated thousands of times throughout the years — something as automatic as brushing his teeth or tying his shoelaces.

And then there were the times when he’d make all the passengers laugh, but unintentionally. “We’d land in Los Angeles, and I’d announce, ‘Welcome to New York! The local time is 3 p.m.!'” he said.

He made dinner plans with relatives in Atlanta, thinking he was flying there, when his flight was actually headed for Phoenix. Van Buren’s supervisors scrutinized him more closely; his relatives, annoyed, accused him of being inconsiderate and irresponsible.

He is especially passionate about raising awareness of Alzheimer’s incidence for African Americans, who not only have a higher prevalence of the disease but more severe outcomes.

Then one day in 2015, at 30,000 feet, Van Buren suffered a heart attack and collapsed while working a flight from D.C. to Rio de Janeiro.

“As luck would have it, there were two cardiologists on board, and they saved my life. I was in such bad condition. They said I died on the plane and they were surprised I even survived at all,” he said.

After an emergency landing in San Juan and two weeks in a hospital there, Van Buren returned home to Charlotte and decided it was time to pay attention to his health. He was overweight, with Type 2 diabetes and heart disease.

His first step: Bariatric surgery to help him lose the extra pounds that had plagued him throughout much of his life. But the surgery was not to be. As part of the evaluation, Van Buren was given a series of psychological tests at the age of 64.

“I flunked royally. The doctors sent me for a thorough neurological evaluation,” said Van Buren. An MRI and subsequent PET scan confirmed early-onset Alzheimer’s, an uncommon form of dementia that affects people younger than 65.

Family History of Alzheimer's

More than five million Americans have Alzheimer’s disease, but only 5% develop symptoms this early.

Though experts are not sure why someone under 65 develops the disease, they do know that genetics can play a role. Van Buren’s mother, aunt and grandmother all suffered from Alzheimer’s. And he was well-acquainted with the impact of the disease: he cared for his aunt and mother, who lived together, until they died.

Upon learning his diagnosis, Van Buren was mired in denial; then promptly took a leave of absence from his job. He fell into a deep depression. For months, he struggled to get out of bed, asking himself, “Why bother?”

His sleep suffered. He became socially isolated, losing all interest in everyday living. He finally quit his flight attendant job in 2018 after using up all his medical leave.

A few weeks after his diagnosis, a postcard arrived from AARP, inviting Van Buren to a local workshop called "Life Reimagined," an initiative encouraging people over 50 to examine their past and create exciting futures. The idea of talking to, and helping, others hit a nerve for Van Buren, who had enjoyed a prior career as a mental health therapist, after getting training in the Navy.

His Life Reimagined

Once his depression lifted, he acted on it.

“I figured, why not? When you come to a bump in the road, you have a choice of remaining stagnant or changing," Van Buren said. "At that moment, I decided I wanted to move forward — and become an advocate for Alzheimer’s.”

That trajectory took Van Buren on a new journey, one he embraces with all the passion of his past.

He serves on the Dementia Action Alliance advisory board, comprised of people living with dementia who advise the Alliance, a coalition focused on empowering people and families living with the symptoms. And as a member of the Alzheimer’s Association's early-stage advisory group, he leads group discussions for others with early-onset Alzheimer’s.

“It really helps meeting other people who have the same thing I have,” Van Buren said.

He’s also a regular speaker on radio shows and at conferences, and is especially passionate about raising awareness of Alzheimer’s incidence for African Americans, who not only have a higher prevalence of the disease but more severe outcomes.

Help From Technology

You may wonder how Van Buren, who lives alone, manages all this.

“I have two roommates,” he told me. Their names? Alexa and Siri, the glue that holds his life together. Alexa wakes him promptly at 7 each morning, and reminds him where he left his keys. Siri tells him when to take his medication and what appointments are on his calendar.

“Without them, I wouldn’t be able to live alone,” he said. His food is delivered weekly from a meal delivery service (“Tonight is filet mignon!”) and these days, lets Uber or Lyft do the driving for him.

Alzheimer’s disease is the sixth leading cause of death in the United States, and is projected to grow to affect nearly 14 million people by 2050. And though there’s currently no cure, Van Buren remains upbeat.

“I love my house — especially my man cave, where I watch way too much CNN,” he joked. And under the blazing stars each night, Van Buren savors time in his hot tub to unwind and reflect before turning in.

He may have lost part of himself, but he’s found someone he recognizes from his past: the resilient, positive person who, at his own admission, always seems to get through everything.

“I’ve always been a people person, and Alzheimer’s has given me the opportunity to do what I really love doing — advocating for people. I’m the happiest I’ve ever been in my life," Van Buren said.