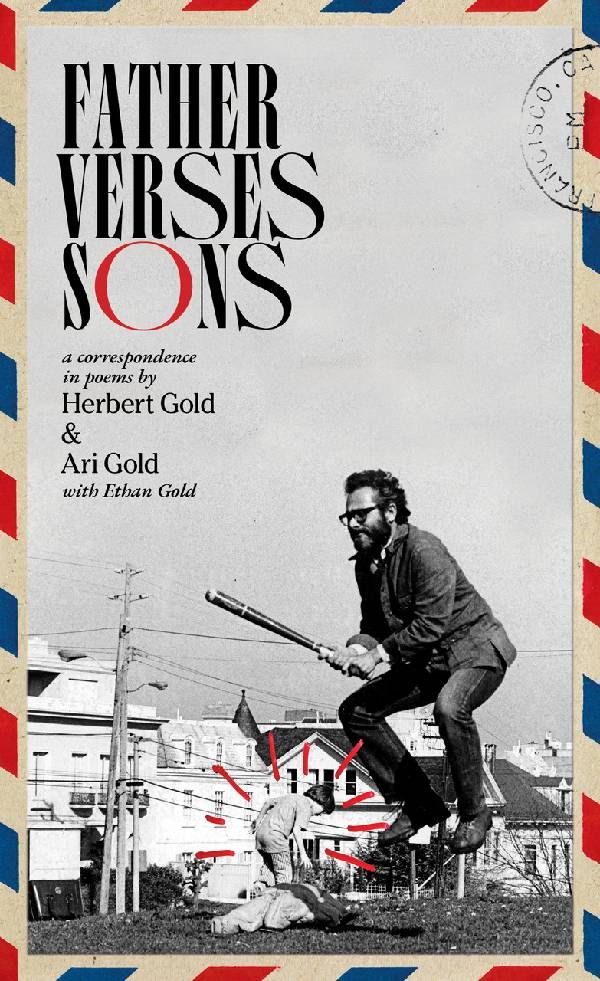

In ‘Father Verses Sons,’ Author Herbert Gold Meets His Gen X Sons at Life's Horizon

This unique poetry collaboration between a prime author of the Beat era and his Gen X sons is a 'volley of voices' that began as an exchange of letters

At the age of 99, author Herbert Gold gripped his pen urgently each morning, in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic, his arthritic fingers compressing every precious word with as much meaning for his children as time and strength would allow.

Herb, who was a treasured friend, hoped to reach his 100th birthday on March 9, 2024. But following serious health episodes last year, he became more keenly aware of his mortality. Never one to lose the humor of his perspective, though, he told the editor of Scribner's "Best American Poetry of 2023," which would include one of his verses, "The first hundred years are the hardest, but the second hundred years present their own problems."

"He was severed from the things that sustained his spirits: the human carnival, and his own creativity."

Sadly, Herb died just before last Thanksgiving, four months short of his centenary. His sharply focused poems, though, are being celebrated on March 9, with the publication of his final book, coauthored with his twin sons, Ari and Ethan Gold. The launch event for "Father Verses Sons: a Correspondence in Poems," is set for San Francisco's famed City Lights Bookstore, which had stocked his 35-plus titles, of fiction and non-fiction, over the decades.

'Scribble Me a Poem, Dad'

This decidedly unique poetry collaboration between a prime author of the Beat era and his Gen X sons was germinated in the loam of letters they began to ward off the isolation of the pandemic.

Ari Gold, a Los Angeles-based writer and filmmaker, explains in his introduction to the cleverly titled "Father Verses Sons" that a few weeks into a global lockdown, he realized that his dad, who lived independently in San Francisco, was mostly alone, aside from limited visits by his two daughters and friends.

Ari writes, "He could no longer see the keys of his typewriter. He could barely hear me on the phone. He was severed from the things that sustained his spirits: the human carnival, and his own creativity."

Ari, one of Herb's three children from his second marriage, snail-mailed an invitation to his computer-averse father with a self-addressed, stamped envelope. He urged, "Scribble me a poem, dad, / but it must be me I'm commanding, dreaming of the Baltics, / facing a palm tree, / waiting for hummingbirds / to meditate along with me."

To Ari's delight, "My dad complied with the vigor of a young poet ... , and written with the urgency of someone who has little time to dawdle. Soon we were making up for human contact by mailing poems back and forth – about love, romance, sex, death and tomato soup." Especially motivating his father, Ari states in the book's introduction, "Mortality is the imagination's greatest engine."

"My dad complied with the vigor of a young poet ... , and written with the urgency of someone who has little time to dawdle."

Ari continues, "I wandered through words. He sliced to the essential experience of outliving his friends, his enemies, his wives, his lovers, even one of his five children. I wrote about nature, disaster, and my own dreams; he responded with poems about the love of his life – my mother – who'd left him first in divorce, then later in a helicopter crash. And I tried to forgive my father his imperfections, through poems that promised I would live on."

Later, when Herb's responses flagged, Ari's twin, Ethan, an LA-based musician, bought a book of stamps and "got our dad going again" with his own verses. Unlike their sisters from Herb's two marriages, his sons neither married nor had children. In one poem, Ethan writes reassuringly to his literary parent, "I always liked a museum, / the idea of permanence through art. / A balm for the childless." Later he invokes "the transfer of dreams / from generation to generation / ... through our hands, not our genitals!"

The new book's cross-generational perspective, with Ari and Ethan in their early 50s and Herb, born in the Jazz Age, survives not only the test of uniqueness, but "Father Verses Sons" achieves a distinctive, sometime discomfiting candor across the authors' parental divide.

Love, Marriage, Trauma

It was my great privilege to have had Herb Gold anoint me as one of his "pals" and converse frequently with his warm spirit and mortality-revved imagination. Almost every week, I'd ascend steeply, but more slowly than the hummingbirds that visited his living room window, to Herb's funky "Beatnik hovel" atop San Francisco's Russian Hill. From that rent-controlled apartment, since 1960, he would gaze down over Chinatown's rooftops to watch the world's ships glide under the Bay Bridge. He'd often mused about his nearing century of life, lamenting the loss of his contemporaries – "I'm the last one."

"Someone famous will die that day, / My day, / And the newspaper will report: / 'More obituaries on page 24.'"

One of his poems in the new collection brushes poignantly against Herb's disappointment that his rich prose oeuvre has been largely forgotten by the literary realm. He imagined his obituary to appear with, as one verse is titled, Other News on Page 24: "Someone famous will die that day, / My day, / And the newspaper will report: / 'More obituaries on page 24.'"

Far from wallowing in self-pity, though, this poem seals his commitment to the nurturing power of friends and family. (His New York Times obituary declared, "Herbert Gold, Postwar Novelist of Love and Marriage, Dies at 99.") Herb wrote that beyond"the curiosity of some, / the regret of several" is "the grief of a few. / Those few, they matter." The poem imagines them assembling in the green and fragrant Marin headlands across from San Francisco, "where I'm proud that the few gather trash, / But drop my ashes downwind, / And remember as I fly away."

In fact, on his day, Nov. 19, 2023, the death of former First Lady Rosalynn Carter did dominate the headlines. And Herb's New York Times tribute filled most of a page, concluding with this obituary poem, printed in its entirety. (It's the same poem also in Scribner's "Best American Poetry of 2023.") Also, the San Francisco Chronicle started its tribute on the following Sunday's page one.

Gen X Children With a Difference

Since Herb died, I've deeply missed our precious time together in his shoebox of a living room. I'd arrive to see him enthroned in his high-backed Victorian rocker, always fixed with complete concentration over a manuscript or his daily New York Times.

Since Herb died, I've deeply missed our precious time together in his shoebox of a living room.

Usually, I had to shout, "Herb, Herb! I'm here!" Not until I was nearly under his nose would he jump and laugh and say, "Wait – I'll get my hearing aids." He'd quickly shuffle up the hall in his rumpled black sweatshirt, soon returning, his hair arced up in tall white egret wisps, his smooth hazelnut face breaking into a smile.

We'd dive into the day's headlines, so troubling. Often, events would evoke a library catalogue of friends and colleagues whose names define much of 20th American century literature: Allen Ginsburg, "Jimmy" Baldwin, Saul Bellow (his mentor), Francine Prose, Ralph Ellison, Vladimir Nabokov, Shel Silverstein, William Saroyan, Diane Di Prima, Philip Roth, Jack Kerouac (whom he disliked). While acutely aware that all were gone, Herb never let disappointment or his failing eyes and ears dry up his pen.

We shared much, such as family roots in the same Ukrainian town; our Jewish mothers having made BLT's for their kids with bacon, presumably too delicious not to be kosher; and our both having Generation X children.

An intriguing difference for me, though, was that for Herb, as a World War II veteran, his Gen X kids came in midlife with his second marriage. That was a full generation later for him than my daughter's arrival was for my twentysomething baby boomer self. Those additional two decades strikingly alter the parental dialogue. In "Father Verses Sons," boomer parents will likely notice a more urgent and candid conversation between the Golds than they are having with their own middle-aged kids. So much to say, so little time.

The father-and-sons volley of voices in "Father Verses Sons" conveys a frankness that is unusual in the poetry of malehood. Midlife masculinity flexes its doubts in Ari's "Female Company," where he confesses ambivalence at finding himself to be a gray Lothario. He catches a sardonic glimpse of himself worthy of his dad and writes, "I'm in New Mexico, I think, / looking for female company / in a sandy hippie café / ... and I'm either the young buck or the old man, depending who's looking."

Elsewhere, Herb confesses, in "Diagnosis & Verdict,"

Even well into my eighties

I thought I was a young man.

I knew I would die someday

But the diagnosis would have to be

He died of the complications of young age.

Haunting "Father Verses Sons" is the family's traumatic loss of Melissa Dilworth Gold, Ari and Ethan's mother. In "Melissa (1943-1991)," Herb recalls, "to celebrate our divorce, / she sweetly brought me a spider plant / 'Because they never die,' she said. / Tendrils green, hanging like dreadlocks."

Sorrow and Reconciliation

Melissa had parted with Herb in 1975, after eight years of marriage. Ari, Ethan and their sister Nina were in their early 20s when, as Herb continues this jarring memory: "There was a storm. / There was a helicopter. / 'She didn't die,' our sons and daughter say, 'She was killed.'"

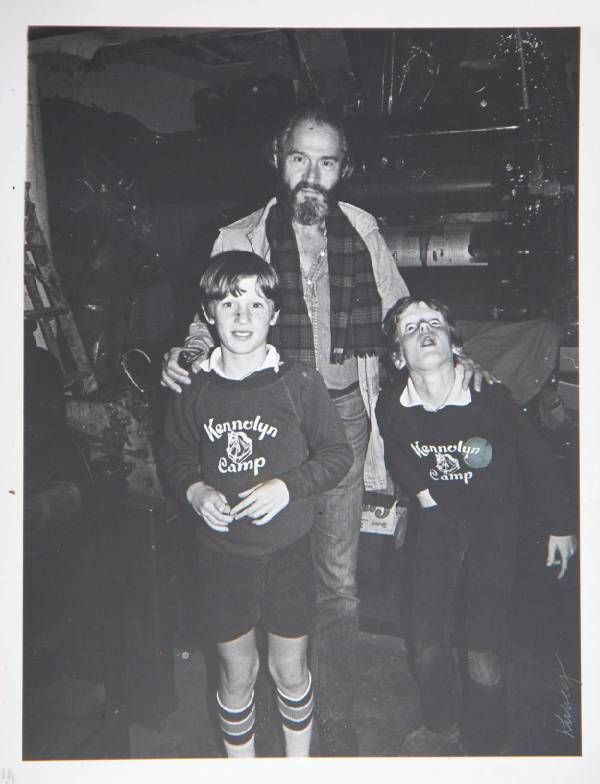

Among the many photographs displayed among the book's poems is a news clipping showing the tangled remains of the Gold family's calamity. The deadly twist of metal is barely recognizable, jack-knifed high in a power-grid tower. The helicopter crash that gale-fated night in 1991 claimed the lives of Melissa Gold and her fiancé, rock impresario Bill Graham. In Ari's award-winning short film, Helicopter, rock stardom, its headlines and celebrity gawkers at the betrothed couple's memorial, would intensify the sorrow of Melissa's children, and shadow this book.

The Golds' aching honesty offers a glimpse of father-son conflict and reconciliation that rarely finds renewal so directly in contemporary literature. In these poems, readers will catch an updrift with the hummingbirds to a window on this family's intergenerational, final reckoning.

Editor’s note: "Father Verses Sons: A Correspondence in Poems," by Herbert Gold and Ari Gold with Ethan Gold. Los Angeles, Calif.: Rare Bird Books, 258 pages. Publication date: March 9, 2024.

Read More