Fighting for the Forgotten

Alabama native Beth Shelburne quit a promising career in TV news to pursue criminal justice reform in her home state — one case at a time

Of the countless news reports that television station anchor and reporter Beth Shelburne has produced, the story of Alabama's maximum-security Tutwiler Prison for Women marked a turning point in her career — and her life.

When the nonprofit Equal Justice Initiative filed a complaint with the U.S. Justice Department in 2012 on behalf of 50 inmates alleging widespread sexual violence and harassment at the prison, Shelburne broke the news on WBRC-TV, the Fox affiliate in Birmingham.

In her tenure at the station, she filed more than a dozen investigative stories about abuse and deplorable conditions at Tutwiler, including revelations that prison guards had impregnated several inmates.

'Vile Behavior' by Correction Officers

Her reporting also revealed details in a scathing report by a U.S. Department of Justice team assigned to investigate the Equal Justice Initiative's complaints. "Women prisoners at Tutwiler live in a toxic environment of rampant sexual abuse and vile behavior by prison personnel," the federal investigators said in a report of their findings.

They found inmates being forced to perform sex acts in exchange for basic sanitary supplies, male officers openly watching women shower or use the toilet, a staff-facilitated "strip show" and punishing prisoners who reported the abuse.

"Alabama is a complicated place. On one end of the spectrum is a horrendous prison system . . . and at the other end are brave, wonderful people working to change the system."

"The Tutwiler story really cracked it open for me," Shelburne said. "It was a really horrific litany. I did a single story and the phones in the newsroom have been ringing ever since."

Those news reports marked a consequential twist in the life of Shelburne, a Birmingham native who traversed the country climbing the broadcast news career ladder, but returned home in 2010 to become one of the preeminent chroniclers of the state's troubled criminal justice system.

"Alabama is a complicated place," Shelburne said from her home office. "On one end of the spectrum is a horrendous prison system, horrible demagoguery, horrible racism and injustice, and at the other end are brave, wonderful people working to change the system."

So, Shelburne, now 49, has remained in Birmingham, to be part of that change.

Formative Years Set Her Trajectory

Shelburne grew up in Homewood, a city of about 27,000 people that shares a border with Birmingham and is known for its more progressive politics and attitudes than much of the state. She now lives in Birmingham with her husband, Kevin Storr, director of communications at University of Alabama Birmingham's School of Health Professions, and their 16-year-old daughter.

She earned a bachelor's degree from Auburn University with a double major in mass communications and journalism. An internship in New York in her senior year "sort of began my journey to leave Alabama," but after about a year-and-half of "really not finding anything that felt right," she returned for a job at WVTM, the city's NBC affiliate.

She was there long enough to meet Storr, who was a sportscaster at the station, before her career sent the couple hopscotching across the country, where she worked for four stations from San Diego to Boston. The couple envisioned remaining in Boston after their daughter was born there, but Shelburne was laid off from the regional cable network where she worked. Around that time, a position opened at Birmingham's WBRC. At first, she didn't consider applying.

Back Home to Birmingham

"What it really came down to is, if we were going to live closer to our families, it seemed like a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity," Shelburne said about her decision to return as the station's weeknight anchor and investigative reporter.

Following the Tutwiler stories and some basic federally supervised reforms, Shelburne continued to report about abuses in the state's prison system, ranging from dangerous overcrowding, unmitigated violence and a death rate — including suicides — five times the national average. Alabama incarcerates more residents per capita than any democratic country on earth and 41% more than the United States overall.

This has provided a rich vein of stories for Shelburne to uncover, including the DOJ's protracted investigation of inhumane conditions in the state's 14 prisons and its decision in 2020 to sue both the state and the Alabama Department of Corrections. The suit is set to go to trial in November.

The Heart Speaks

As Shelburne became immersed in the seemingly intractable problems facing the state's criminal justice system, she felt a disconnect between the need for deep, sustained reporting to expose the problems, and the limitations of TV news. "You cover the crime, you may cover the conviction, and then you move on," she said.

As that conflict became more acute, Shelburne's dissatisfaction grew, but "I was making a lot of money," she recalled. "You have those golden handcuffs."

To develop longform narrative journalism skills, Shelburne enrolled in a master's program in creative writing at the University of Alabama Birmingham, on top of her full-time anchor-and-reporting job.

Deciding to Leave TV

Six days after defending her thesis in April 2018, Shelburne, then 43, suffered a type of heart attack called spontaneous coronary artery dissection, better known as SCAD. It often strikes young, healthy women with no history of heart disease, but may be triggered by stress, among other factors.

"I made the decision the first night I was in the hospital that I would take myself off air," she recalled. "I realized I needed to do everything I could to get myself into a happier place."

Shelburne went from earning a six-figure salary to making $15/hour as a part-time digital reporter at WBRC, with plans to fill the rest of her time with independent passion projects. "It probably wasn't the best business decision, but I sleep well at night," she said.

The Human Cost of Harsh Law

While recovering from her heart attack, Shelburne applied for and was named a PEN America Writing for Justice Fellow, which supports writers pursuing substantive projects about mass incarceration. Her topic — a group of aging men in Alabama sentenced to life without parole for petty crimes committed decades ago — was an extension of her master's thesis.

She detailed that work in 2020 in a nearly 10,000-word article published by the news website The Daily Beast. It chronicled the human costs of Alabama's Habitual Felony Offender Act, a 1977 law that mandates life imprisonment without parole for persons convicted of a Class A felony — including those that do not result in physical injury — if they have been previously convicted of any three felonies, no matter how minor.

"Her willingness to share all her research is just amazing."

Shelburne painstakingly told the life stories of men sentenced to die in prison for crimes sometimes no more serious than third-degree burglary.

That work evolved into a partnership with the Alabama Appleseed Center for Law & Justice, part of a network of 18 organizations across the United States and Mexico committed to reducing poverty and ending discrimination. When the center wanted to examine the Habitual Felony Offender Law, its then-new executive director, Carla Crowder, turned to Shelburne.

"Beth had the data and the information to open that window," Crowder recalled. "Her understanding of who these folks are and how sympathetic they are and her willingness to share all her research is just amazing." That alliance has led to the release of 16 men in the past four years, at least five of whom Shelburne directly referred to Appleseed.

'Most Gratifying Thing I’ve Done'

Shelburne considers her work about the habitual offender law as "one of the most gratifying things I've ever done," adding that among the people who've been released, "the recidivism rate is zero."

Shelburne has befriended some of the men she has helped free, including Ron McKeithen. Raised in poverty and neglect, McKeithen, had, by 18, racked up charges for illegal possession and fraudulent use of a credit card and third-degree burglary. Then, he and a buddy in 1983 robbed a convenience store clerk at gunpoint, saying the clerk owed them money. No shots were fired and no one was physically harmed, but the offense made McKeithen, at 21, among the first ensnared by the multiple offender law.

Thirty years later, despite completing roughly 100 prison educational and behavioral programs, living in a special, application-only faith-based honor dorm, teaching and mentoring fellow inmates, and filing several court petitions, McKeithen remained locked up in the state's maximum-security William E. Donaldson Correctional Facility. He met Shelburne when she interviewed him for a documentary about an educational program offered by the prison and UAB.

She persuaded Appleseed to pursue his appeal, and he was released from prison in December 2020, at age 60, after serving 37 years. "I could see reflected in Beth's eyes that she really understood who I was," McKeithen recalled in February, while celebrating his 62nd birthday in Last Vegas. "I didn't have to convince her that I was a good guy."

Not Without Sacrifice

In addition to the financial hit her career detour exacted, Shelburne unsurprisingly has faced hostility from state agencies and officials unhappy with her work.

After particularly damning reporting on prison deaths and corruption, Shelburne has twice been unceremoniously dropped from news media lists of both the Department of Corrections and the governor's office, and had her requests for information completely ignored, the last time for a year-and-a-half before new leadership restored her access. "It's a hell of a thing to feel that kind of hostility from a government agency," Shelburne recalled.

In both instances, Shelburne's news colleagues rose to her defense, drafting letters that garnered signatures from journalists from throughout Alabama and the country.

"Cutting Beth out meant cutting out a perspective we desperately need, even if our state leaders prefer to ignore it," Alabama press corps veteran Brian Lyman wrote in an email about the first open letter drafted on her behalf.

Prosecutor Urges Focus on Victims

Officials at the Department of Corrections and the offices of Governor Kay Ivey and Alabama Attorney General Steve Marshall did not respond to several requests for comment about their relationship with Shelburne and her work.

C.J. Robinson is district attorney in Alabama's 19th Circuit and chairman of the state's preeminent crime victims' organization, Victims of Crime and Leniency (VOCAL). Robinson's largely rural district is home to four state prisons and will be the site of a $1 billion, 4,000-bed "super-max"-style prison, the most expensive ever built in the country, and slated to open in 2026.

While commenting that he thought Shelburne's work for WBRC has been solid, Robinson said too much attention is paid to the rights of the incarcerated, and too little to crime victims and deterring future crimes.

Reform Could Reduce Recidivism

"This never-ending cycle that we find ourselves in in Alabama — that we continuously reduce sentences, reduce sentences and reduce sentences — is not in the best interests of the victims," he said.

Robinson, however, acknowledged that the state's prison system needs reform, including addressing its "dilapidated facilities, lack of programs, and a sheer shortage of people needed to supervise prisoners."

"If all those things could be improved," he added, "I think we'd see a better product and lower recidivism."

That a tough-on-crime evangelist like Robinson concedes the severity of the issues Shelburne covers demonstrates the power of her work and her credibility as someone from Alabama. "It's harder to challenge criticism from a native daughter," Appleseed's Crowder observed.

"Earwitness" Podcast

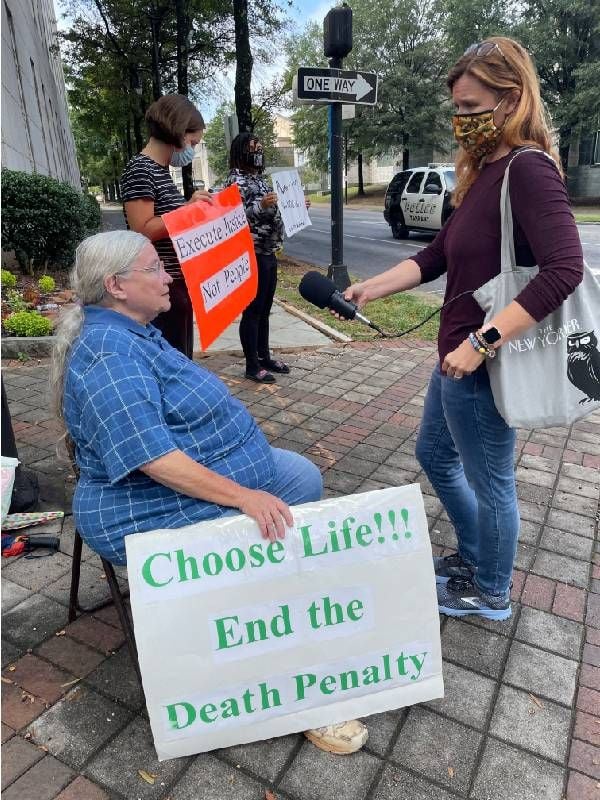

One of Shelburne's latest projects is a podcast series funded, co-produced and distributed by multimedia platform Lava for Good titled "Earwitness," about Toforest Johnson, an Alabama man who has spent the last 25 years on Alabama's death row for the murder of an off-duty Jefferson County sheriff's deputy.

"This never-ending cycle that we find ourselves in in Alabama . . . is not in the best interest of the victims."

With 10 alibi witnesses placing Johnson at a nightclub four miles from the scene of the murder and no forensic or physical evidence implicating Johnson, he was convicted on the testimony of a single "earwitness" — a woman, Violet Ellison, who told police she overheard Johnson confess to the crime on a three-way jailhouse phone call. Ellison received a $5,000 reward from the state for that statement, which officials kept secret for 17 years.

Attempts to secure a new trial for Johnson have been unsuccessful, although he remains a pro bono client of the Southern Center for Human Rights and the Death Penalty Clinic at the University of California Berkeley School of Law, which continues to pursue his exoneration.

Call for New Trial Is Ignored

The podcast took Shelburne two years to research, report and produce. The final episode was released in late 2023, and featured interviews with the state's former attorney general, the county's current district attorney and the former assistant district attorney who prosecuted Johnson, all agreeing that Johnson's conviction should be overturned, and a new trial held, which state officials so far have refused to do.

Shelburne will teach a class on podcasting at UAB this fall, and is waiting to hear on another national fellowship that would underwrite a significant new reporting project. Regardless of what's next, she's comfortable where she's landed.

"There are a lot of things Alabama symbolizes to people that are offensive, but it's not the entire story," Shelburne said. "We also have a great history of resistance, and courageous people who don't accept the status quo.

"It's a place that's challenging, and that can be really exhausting, but it also can be really rewarding. I like to think I'm doing something that's changing the world for the better."