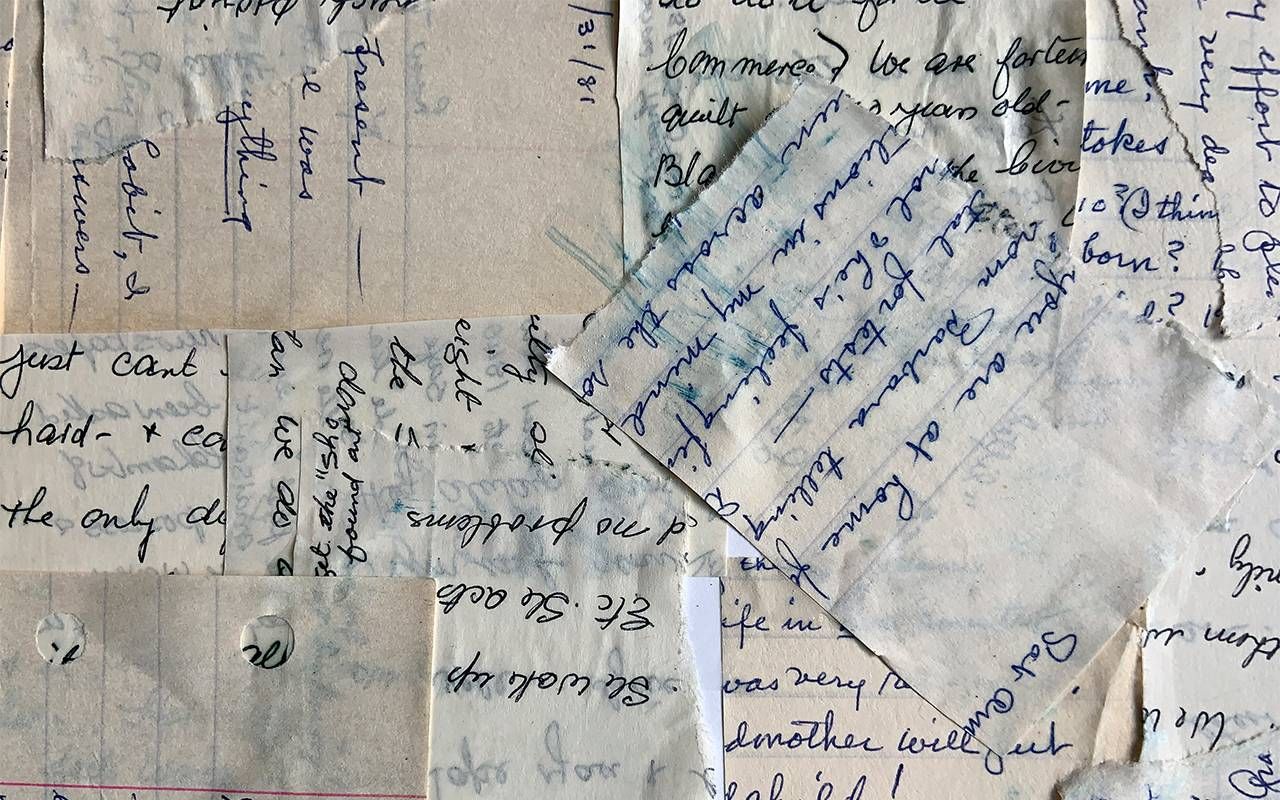

Finding My Mother's 'Talk' In Her Handwriting

Handwriting is living talk. Type and talk-talk can make me feel like I'm drowning, but handwriting breaks me apart.

People say too many words. The talking heads on the news shows I'm addicted to, turning each event into "breaking bombshells!" Everybody on social media. Me.

That's the worst. The spasms to myself about what I did wrong, whatever is my frustration du jour, my judgments about what everybody else is doing — like talking too much. Too much talking is why I write. To get it succinct.

I'm a writer, the daughter of a deceased writer whose distinctive handwriting I'm staring at because a money-grubbing relative who can't shut up and never knew my mother has nudged me to claim some unclaimed funds 33 years after Mom's excruciating demise.

Just the sight of her cursive F catapults me into the meeting she took me to where the lawyer lectured her about a living will ...

Fri 24th — 2:30 and the name of the law firm that executed Mom's will. Just the sight of her cursive F catapults me into the meeting she took me to where the lawyer lectured her about a living will ... which leads to the memory of how she followed orders but abandoned that living will when she switched to a doctor who gave her delusional hope…demolished once she was moved to a ventilator with tubes in every orifice, and how, when I, her third-party power-of-attorney advocate and executrix, found said living will, the delusional doctor yelled, "Don't you dare bring that thing in here. She never talked to me about living wills, and if they see it, they'll make me stop feeding her."

My Mom's Wishes

Clipped to her Will documents folder, her careful script names her bank accounts and instructs — me? her? — that they're in checkbook and desk drawers — Oil Division Orders in dining room closet shelf.

And my heart is pounding and it's thirty-three years ago and I'm standing in her vacuum of an apartment, knowing to go to the closet to get the bag of division orders that I then lug to the lawyer, who exclaims: "Abandon them! This is the kind of stuff that ties up an estate for years. It'll cost more than the estate to get local counsel all over the Midwest to claim them. Get rid of them!"

And then I'm here in 2023 buried in forms to claim them because I followed those orders, and I feel guilty. Guilty that I disobeyed even though she compulsively told me that if anything happened to her, I was to find the mineral and oil interest leases that had come from her uncles in Oklahoma and claim them. Here I am, four years older than she was when she died, bawling like a little kid who knows she did wrong.

Here I am, four years older than she was when she died, bawling like a little kid who knows she did wrong.

Is it the words or the handwriting?

Handwriting is living talk. Type and talk-talk can make me feel like I'm drowning, but handwriting breaks me apart.

My mother, Edna Robinson, was a mostly frustrated fiction writer. Her Will documents folder has a carbon copy of a letter to her lawyer mentioning the novel she was writing that she hoped would be the most valuable property of her life.

When I appropriated her manuscripts (she left them to me), there was no book — just miscellaneous pages and notes. What was fully birthed was the book she wrote in 1959 and, when she couldn't sell it, closeted with less belief in its worth than the oil leases.

No matter what publishers had said, I considered it valuable, so I edited and got it posthumously published. During the process, I laughed and cried and yelled at her, but that was different from reading handwriting — things she wrote to and for herself.

Her Journal Pages

Since I'm already back in 1990, I pull out a blank journal that her front-of-book handwriting says is From Betsy 12/25/76 — when I was living the life of a young writer/actor with delusions of my own and she was working full-time writing advertising for cosmetics and cookies.

She saved my gift note in dictatorial block print:

Dear Mumsy,

This is a blank book. You have 365 days to fill it. DO IT! If you're not going to write stories, the least you can do is write a book.

xox, your daughter and cheerleader, Betsy

And, even though it was a joke that we both laughed at, I cringe at my youthful ignorance and arrogance, my lack of understanding about her and her history and why she might be paralyzed and more prone to talking about writing fiction than doing it.

Her first blank book entry was probably that Christmas evening:

12/25/76

I figured out why, at even the most unlikely times, I like to play solitaire. I have no control over the cards: that's understood from the beginning. They fall into the right pattern — or no pattern — by chance. I can only hope to win. The only time in my life when I can't delude myself into believing that what I do makes a difference is when I turn the cards and admit I'm at their mercy.

And her last entry for that year:

1/17

Moments of startling understanding are easy. Have an energy of their own. Surprise. Thrill content. When a friend dies — the shock — the sudden awareness that your own life has more meaning. Simply because it is. You exist & the other no longer is. It's the aftermath — now that you know this — that's difficult.

Mothers are expected to have certain fears for their daughters, other ones for their sons. They are not permitted specific fears to do with themselves — as adult children aren't allowed infantile insecurities.

And the next and final entry, written in the back of the book after six years of blank pages:

3/14/82

The secrets change. In corporations middling people never reveal their salaries. In Tulsa in the late 30s no one talked about Indians and colored peoples' curfews: First Avenue (street) on Saturday night was a different world. Mothers are expected to have certain fears for their daughters, other ones for their sons. They are not permitted specific fears to do with themselves — as adult children aren't allowed infantile insecurities.

It was inner talk, the kind of thing that tortures me, but because it's hers, in her handwriting, I turn infantile, missing my mom, and melt in a love puddle. Do I owe the money-grubbing can't-shut-up relative a thank you? Perhaps, but I'm done talking.