'Geriatric Champions' Are Changing Medicine for Good

A new fellowship in Oregon deepens clinics’ understanding of treating patients

Dr. Subhechchha Shah recently saw an 80-year-old patient with a long list of medical ills, including chronic pain from multiple back surgeries, Parkinson's disease and related dementia.

In the past, Shah would have referred the patient to specialists, who in turn would likely order a battery of tests, procedures and medications. But this time, Shah spent the visit listening to the patient and her husband.

"Falls, for example, are not normal and the risk can be reduced."

"She said she was tired of going to doctors almost every day," said Shah, who is a family practice physician with Providence Medical Group in Medford, Ore. "She said, 'I don't want more medications and more appointments. I want a little more control of the pain and to live my life a little bit better.' I was happy that I was able to have that conversation."

Shah's newfound appreciation of learning what is meaningful to her patients is the result of an intensive geriatric training program she recently completed. The "geriatric mini-fellowship" launched in 2018 by Providence Health and Services in Oregon, is offered to small groups of the system's primary care providers to deepen their understanding of treating older adults. Shah and her six physician classmates met in Portland, Ore. for four one-week sessions, spread throughout the year.

Health Systems Need Help

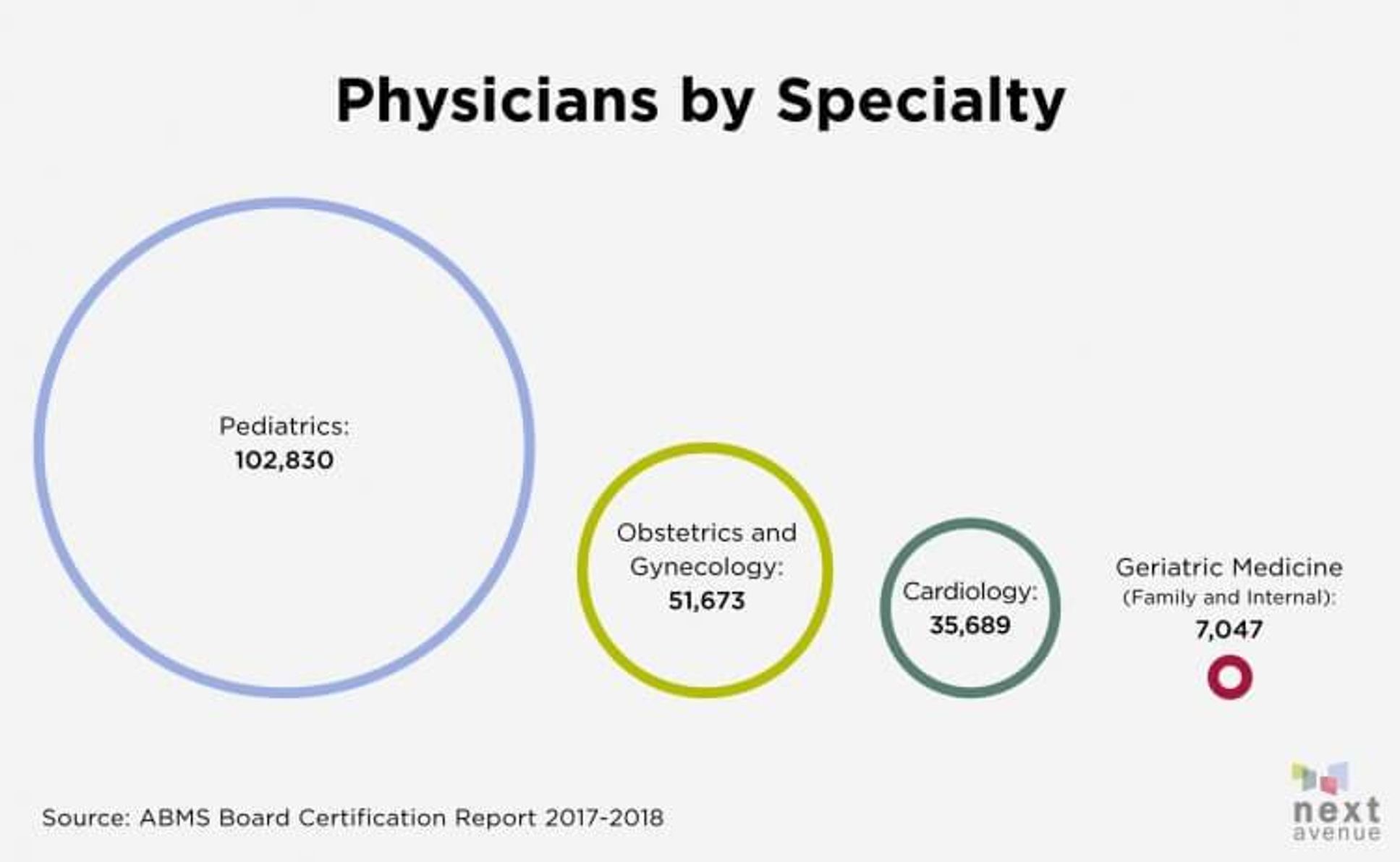

Providence operates 45 primary care clinics in Oregon, whose patient population includes 83,000 people 65 and older. But as of 2018, the state has only 88 board-certified geriatricians — doctors who specialize in the care of older people. And that's not just an Oregon problem. The entire country has just 7,047 geriatricians.

To help provide a fraction of Oregon's older patients with better care, geriatrician Dr. Marian Hodges and geriatric clinical nurse specialist Colleen Casey developed the fellowship. Health care providers welcomed the program. "They all know they do it lousy," Hodges said of geriatric care.

One problem, said Shah, is that physicians have been trained to treat older adults the same as younger ones. Older patients' changing bodies, cognition or social structure are not taken into account. "What we do in medicine is one size fits all — the research, the evidence that we have, is based on the adult population, and we just apply that to the geriatric population," said Shah. "This is a population that needs a different approach."

Beth Ott, nursing quality supervisor at the Providence Medical Group Orenco clinic in Hillsboro, Ore., agrees. In nursing school 15 years ago, she had no training in geriatrics, compared to a three-month rotation in pediatrics. Before the fellowship, she said, the providers knowledge base was "pretty limited."

"We treated these patients like any other patient. But it's a specialty."

To address this gap, Hodges and Casey, working with a nurse practitioner, created a curriculum aimed at transforming providers into "geriatric champions."

"The goal is that they're not just getting smarter about how to care for older adults. They go back and improve the processes of care and serve as a resource for other partners and primary providers," Hodges said. "We know our clinics are not very well structured to take care of older adults — from the front desk check-in for someone with dementia sitting in the waiting room for a long time to someone very frail who can barely walk, let alone get up on the [examining] table. We realized this is a team sport."

The program got a boost from The John A. Hartford Foundation (a Next Avenue funder) and the Institute for Healthcare Improvement, which are partnering on an initiative to encourage age-friendly health care in health systems throughout the country. Providence, one of five systems to receive pilot funds, used the $250,000 grant to help pay for a number of projects geared toward older patients, including this geriatric fellowship.

The Geriatric Mini-Fellowship Curriculum

The fellowship curriculum is organized around key interventions known as the 4Ms: medication reduction and management, mobility (fall risk and function), mentation (dementia, depression, delirium) and what matters to individual patients. Shah's conversation with her patients on quality of life was an outgrowth of the week spent on "what matters."

Program instructors include social workers, geriatric psychiatrists, nurses, physical and occupational therapists, chaplains, older patients and family caregivers who share stories and experiences.

To help physicians get buy-in from their home clinics, the program invites a different staff member from each participating clinic to attend for a day on each week of the fellowship.

"The first week, we had pharmacists come and learn a brief summary of what the providers learned about reducing medications," explained Hodges. "Then we had the pharmacists sit down and brainstorm about how to make the clinic better."

Ott took what she learned from the session on mobility and focused on reducing fall risk at her clinic.

"We started doing a fall-risk screening questionnaire once a year," she said. This involves monitoring any changes that make patients more vulnerable to falls. The team also installed grab bars near the clinic scales. Ott is now part of a fall-risk collaborative and is participating in a pilot project that follows patients who come to the emergency room after a fall.

"We're wrapping our arms around [patients] as far as resources, meeting with the caregiver and family member and doing everything we can to reduce the falls risk," she said.

Since the fellowship, Ott's clinic has an increased knowledge of the needs of their patients as well as more empathy and compassion for their older patients, she says.

Ott brought back disability-challenge exercises to the staff, including role-playing of patients with hearing or vision loss, impaired balance or cognitive decline. In one exercise, participants try to read a medical bill in which numbers and letters are transposed, as a way to demonstrate what patients with cognitive decline may experience. Medical assistants and reception staff participated. "They said, 'This is so frustrating. How are people with mild dementia figuring this out?'"

Clinics Changed for Good

Shah said she learned three key lessons from the fellowship.

The first is that she should focus holistically on the patient, not just the disease or condition.

The second is that she is part of a team. "Now I'm in touch with the occupational therapist, the physical therapist, the nurses. I'm getting more help, and they feel comfortable reaching out to me," she said.

The third is that she learned what "normal aging" is. Falls, for example, are not normal and the risk can be reduced.

Shah now spends more time focused on healthier patients in their 60s and 70s to help them proactively improve their diet, exercise and balance. After coaching one who was mildly overweight with high blood pressure and pre-diabetes, the results paid off. In six months, after the patient improved her diet and went to physical therapy, Shah saw a remarkable improvement. "She had a stable gait and much more confidence," she said.

Finding time for the physician fellows to conduct the staff training at their busy home clinics — and to sustain the momentum — is an ongoing challenge. At Ott's clinic, the team now has daily huddles to review the schedule and identify which older patients might need special attention.

Shah has been conducting education and training for her staff and colleagues in areas such as advance-care planning. The fellowship reimburses each clinic so the fellows can spend two hours a week on their geriatric initiatives. The fellows also meet quarterly to "stay nourished" and will act as mentors to the next group of fellows.

According to Hodges, a highlight of the fellowship is the chance for the physicians to bond and share the challenges they face. "It became a very intimate experience," she said. "It's a small group who were very vulnerable, very interactive. There's tears and laughter. Some were beginning to burn out, and this fellowship helped them renew their passion for taking care of patients."

Editor’s note: This story is part of a Next Avenue initiative on age-friendly health care, with support from The John A. Hartford Foundation.