His Mother's 'Combat Buddy' Gave Luis Alberto Urrea the Key to His New Novel

A Donut Dollie during WWII, Phyllis McLaughlin's wartime experience was traumatic and years after her death, her son learned more of the story

As a young boy, writer Luis Alberto Urrea rarely slept through the night. "I became a teenage insomniac. I could not sleep," he says.

His mother's memories from the front lines of World War II were so vivid and traumatic that she had nightmares for the rest of her life and the sounds of her dreams echoed throughout their home. "You couldn't awaken her or she would jump out of a window," Urrea says. "Nights were very difficult in our house."

"For so many of those boys, the women were going to be the last friendly, caring face they ever saw in their lives and I think the burden of that was pretty heavy."

Urrea knew some of the specifics of his mother's service. As a child, he'd found her box of mementos from the war. But until he began researching his newest novel, "Goodnight, Irene," about a young New Yorker who volunteers for the Red Cross in 1943, the color and the fabric of his mother's experience had been missing.

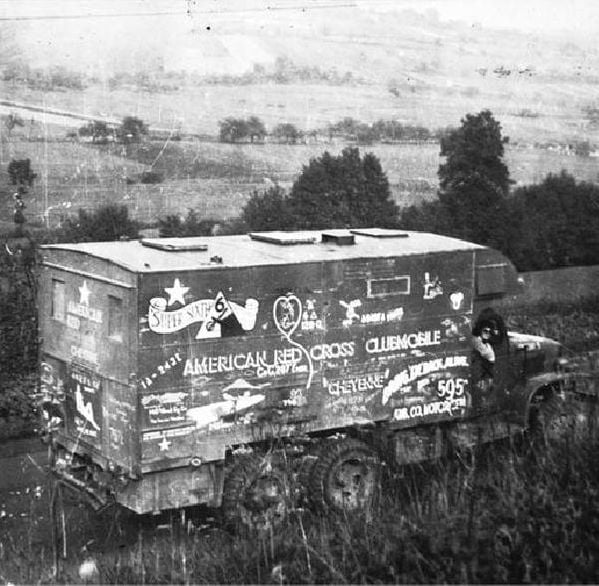

Urrea's mother, Phyllis McLaughlin, was a twenty-seven year old socialite in New York when she signed up with the Red Cross and was assigned to a Clubmobile. "This was like Ike's (General Dwight D. Eisenhower) genius, if you will," Urrea explains.

The Red Cross had set up clubs for enlisted men and officers that were called Donut Dugouts. "It was Ike who thought, 'Let's make it mobile. Let's put the club on the back of a two-and-a-half-ton GMC truck,' which they did," says Urrea.

Donut Dollies

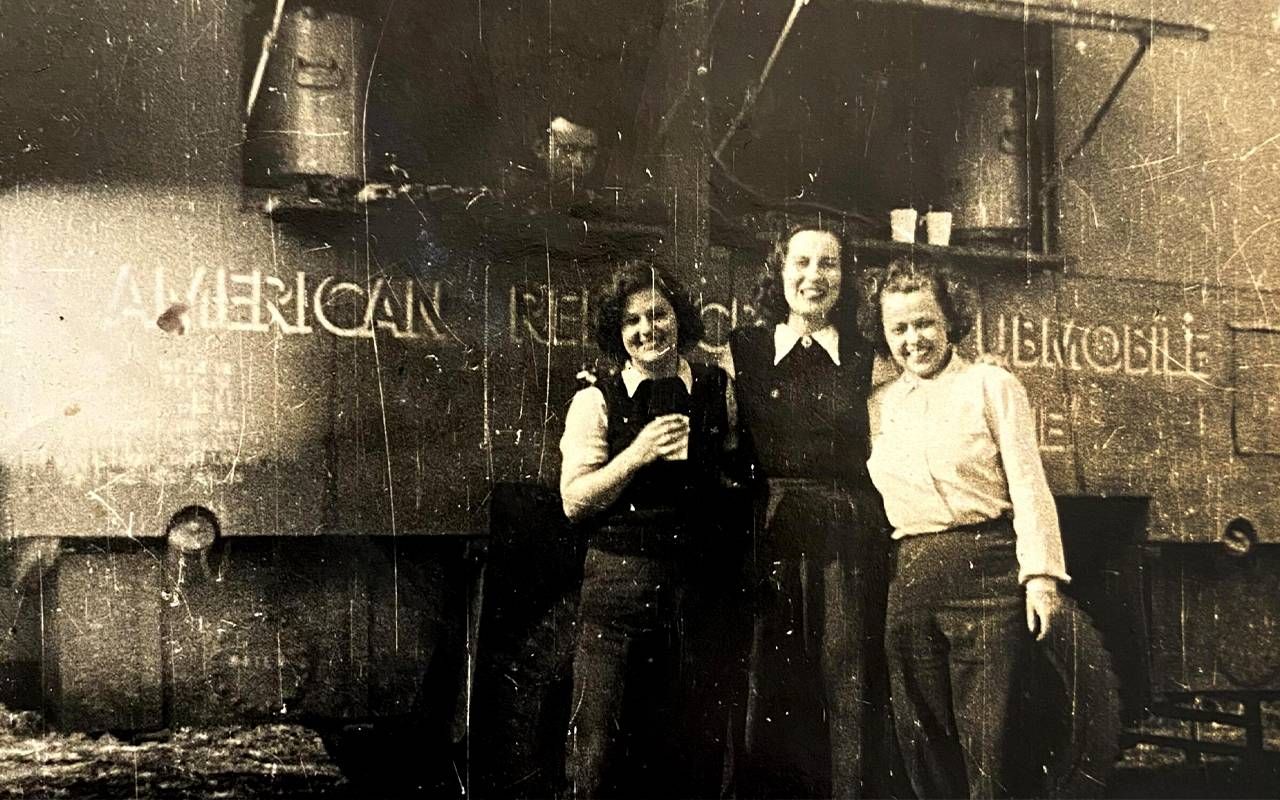

McLaughlin and other Donut Dollies — as they were called, much to the women's chagrin — were deployed overseas with the Clubmobiles. They went first to Glatton, England for training, where Urrea's mother lived upstairs in a house whose downstairs was occupied by film director John Ford's documentary camera crew.

Urrea's mother was teamed up with Jill Pitts, a 6-foot-plus force of nature who drove the truck and who would become one of her dearest friends. Once in Europe, the Clubmobile trucks followed the Allied soldiers as they fought to liberate territory from the Nazis.

"For so many of those boys," Urrea told me, "the women were going to be the last friendly, caring face they ever saw in their lives and I think the burden of that was pretty heavy."

But one of the experiences that haunted his mother most unfolded in a village that McLaughlin and the other women believed had been liberated. As Urrea says, "They got there. They were ahead of the troops. It had been liberated. They thought."

The village mayor, who'd been tortured by the Gestapo, warned them the Germans weren't gone. "He had his little girl and he and his wife begged the women in the truck to hide the little girl and drive her out of there. They turned them down believing that George Patton was on his way." Urrea paused for a moment. "[My mother] had this burden of guilt that she may have denied that child salvation."

A Night of Barbarity

Phyllis McLaughlin also survived a barbarous night, hiding in a hayloft, as German soldiers swept through a village, meting out brutality to the men and women they encountered.

"She hid in a barn with one of her friends, one of her teammates, and they buried themselves in hay because of the atrocities going on outside, specifically atrocities addressed to women. And I think that was the gist of her nightmares because she prayed, 'Please God, let them stay out there, doing what they're doing and not find me.' Urrea thinks for a moment and then adds, "And she felt so guilty about that prayer that she had done something so terrible, but she was so afraid."

"There she was, twenty-seven, glamorous, a hero, going out to save boys in trouble and being the source of joy."

Near the end of the war, Phyllis McLaughlin was seriously wounded in a truck accident. When she later described what had happened, she would say, "And we never found the other girl."

For years, Urrea assumed the other girl was Jill Pitts. But when he and his wife, Cindy, began the research for "Goodnight, Irene," his wife discovered that Pitts had survived the war and was living just 90 minutes away.

"So we rushed down to meet her. She let us in. And on her wall was a framed picture of my mom. And she said to me, 'Luis, I drove the truck, but your mother brought the joy.' And I suddenly saw her. There she was, twenty-seven, glamorous, a hero, going out to save boys in trouble and being the source of joy."

'Miss Jill Gave Me the Key'

Miss Jill, as Urrea and his wife called her, shared scrapbooks, keepsakes and photographs with the writer. "The first day we met her, she showed us that she had the actual map that she had used driving all over Europe and it has her notes on it," says Urrea. "She said, 'I'm willing to share a lot of these things with you but you can't have my map.'"

Luis Urrea's friendship with Miss Jill, which began when she was ninety-four years old, and included long lunches where Jill sipped a Manhattan or two, brought his mother's life into sharper focus. He began to understand who she'd been before the trauma of her wartime experiences. "My mom was heartbroken that she had been broken (by the war.) That something was wrong, but it was uncontrollable." Urrea's mother died in 1990 at age 74.

Jill Pitts Knappenberger did not live to see the publication of "Goodnight, Irene," dying at age 102. But Urrea believes that she understood how essential she'd been to giving him a richer portrait of his mother's life.

"The thing about the novel is that I didn't know how to write it and Jill is the one who gave me the key."