Patti Davis on Ronald Reagan's Alzheimer's: 'His Soul Can’t Be Sick'

Insights from the new book by former President Reagan’s daughter, based on her years running a support group for dementia caregivers

"I now begin the journey that will lead me to the sunset of my life." Those are the words former President Ronald Reagan wrote in a seminal letter to the world in 1994, announcing his Alzheimer's Disease diagnosis.

Now, his daughter Patti Davis is out with a book, "Floating in the Deep End: How Caregivers Can See Beyond Alzheimer's," that's not just about her father. It's also about mine — and maybe yours, or your mom, your partner or any close loved one with dementia.

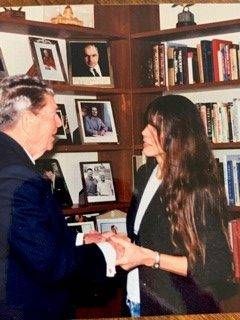

Davis' anecdote-and-advice-filled guide is built on twin experiences: the 10 years she watched her father descend into dementia (material she first explored in "The Long Goodbye," published in 2004, the year he died) and the six years she led "Beyond Alzheimer's," a twice-weekly caregiver support group she founded, originally at UCLA. She now licenses its clinical and emotion-based curriculum to other hospitals and sometimes participates virtually.

Davis' insights from these intimate encounters with Alzheimer's are organized chronologically from "The World Just Changed" to "The End Stages." She includes many strategies for caregivers' hard realities like bathing resistance, creative lying, family discord, managing anger and feeling guilty for laughing when situations turn, well, funny.

Next Avenue talked with the 68-year-old caregiving advocate and novelist, who lives in Los Angeles, about her newest book:

Next Avenue: You've written about your family and about Alzheimer's before. Why this book and why now?

Patti Davis: "The Long Goodbye" was written in journal form as I was going through it. The lessons you learn — they settle with you and get more fleshed out over time. I had more to say about the practical side. Primarily — and why I started the support group — there's still not enough investment in caring for the caregivers, certainly not by the medical community.

The book's essential takeaway is, as you write, 'I didn't believe a person's soul could have Alzheimer's. I made the decision that if I kept reaching beyond the disease, if I kept aiming for my father's soul, I would somehow be able to connect with him.'

It was the first thing that came to me when I found out my father had been diagnosed with Alzheimer's. I was in living in New York when mother (former First Lady Nancy Reagan) called to tell me. As I walked around Manhattan, this thought came to me: He has this illness, I don't know a lot about it. But his soul can't be sick. I knew if I could hang onto that, it could ground me no matter what happened.

What did that look like in practice?

Well, it's not easy when someone is talking word salad and not making any sense; it takes faith. But if you're locked in an attitude of 'Well, they're gone,' you'll miss those fleeting moments when there is an aperture through the disease, when you see they're there.

Once a doctor was talking about my father as if he wasn't in the room, and I called him on it. The look in my father's eyes turned amused — I knew he was thinking, Good girl, you got this exactly right.

Three Things Every Family Should Know at the Start of a Dementia Journey, According to Davis:

1. This disease will bring up everything — in families, in you. It's like this detox of things you thought you dealt with or went to therapy for. It helps to know that, going into it.

2. We all like to think we can control things, but the disease is what will be in control. Obviously, there are steps you have to take or things you need to do, but you're not going to control this disease.

3. There are things Alzheimer's disease can't destroy. It can't destroy love. People anticipate it being so traumatizing when the person forgets their name, who they are. But just because they don't know your name, the disease can't destroy their love for you. That's not centered in their brain. It's in their heart and soul.

Do you think your mother shared your perspective?

Since I was a little girl, my father and I often talked about God, but spirituality was not something I went to my mother with. In my eulogy for her, I talked about how she was determined to be at my father's side when he died — so I said what I thought my father would have said: that it was in God's hands. God knows what he's doing. She frowned and said, 'Well, God can do what he wants, just as long as I'm there when your father dies!'

You really explore the universality and 'okay-ness' of emotions like guilt, denial and grief. Why do you think that even after all these years of understanding more about the disease, so little is said about caregivers' feelings?

I think people are still really scared of this disease. It's like death; there's this feeling that if we talk about it, we'll invite it in, like, I'm going to be next. It is a mysterious disease, and people are uncomfortable with it and scared to talk about it. But it needs to be talked about.

Was there an emotional challenge that you struggled with most?

I struggled with my father's elusiveness. I was never as close to him as I wanted to be, and now this disease was taking him further away, so how do I reconcile that?

But the more the disease went on, the more I realized I was getting to know my father better — I think because I wasn't expecting anything. I was willing to learn and grow into it. In those ten years, I got to know his essence — he was a very sweet person. It's like a palimpsest, something that keeps get stripped away [by Alzheimer's] so you see what's underneath.

Another wonderful line in your book: 'It broke my heart to hear people berating themselves for imagined faults when all I saw was astounding courage.' You're talking about caregivers beating themselves up for perceived shortcomings, like not doing enough or responding the right way or having to place a loved one in a facility. How can caregivers change that self-critical headspace?

Guilt is like this muscle we have — and it's bad and it's good. We need to have it if we do something wrong. But sometimes it gets twitchy and shows up when it's not needed or appropriate.

My method is to talk to that guilt and say, 'Thanks for showing up, but I don't need you here.' It's kind of silly, but I think it works.

Many families, like your own, have fraught or complicated relationships even before the strain of Alzheimer's comes into the picture. You've written a lot about your difficult experiences with your late mother. What are some tools or approaches a family member should know when they're falling into those old patterns — the grievances, power battles, old family roles?

Unfortunately, those relationships are probably not going to change. It's great in Lifetime movies to say, 'Let's rise above this terrible disease!' But in real life, you have to change how you look at it.

Instead of thinking, Here I am in this toxic dance again, take a step back and look with more compassion for that other person. That's not to say they didn't mean how they've treated you in the past; they probably did! But try to see their negative or harsh choices from a different angle, so you can think, How sad for them.

I did this with my sister Maureen (whose mother was Jane Wyman, Reagan's first wife; Davis wasn't told of Maureen's existence until she was 7). She was a very difficult person, and we tried to mend our relationship but really couldn't. While she was dying of cancer [in 2001], I ended up looking at her with a lot more compassion, what her choices were and how she fought death to the end.

What do you think your father would make of your work today?

I think, I hope, he would be proud. My father was this elusive man — there were times in my life where I thought if I turned water into wine I wonder if he'd notice? But I'd like to think he'd be proud — and happy I'm not the resentful child I once was.

The following is an excerpt from Davis's new book, "Floating in the Deep End: How Caregivers Can See Beyond Alzheimer's"

The World They Have Created

I don't know what worlds my father drifted into. I wish I did. There were glimpses in the earlier stages of who he was as a boy, as a young man, and I felt that I had gotten to know a bit more about him, this man who had always mystified me. But he grew silent at a certain point; he basically stopped talking except for a few syllables once in a while. Sometimes I saw him moving his hands in a very deliberate way and I tried to figure out if he was reining in a horse or doing ranch work. I had only my imagination to fill in the blank spaces. But wherever he was, he seemed content.

One day when I visited him, not too long before he died, the song "Danny Boy" was running through my head. I had been listening to Eva Cassidy's rendition of it earlier and it had stayed with me, partly because my father used to sing it to me when I was very young. He was, as usual, lying on his back in the elaborate hospital bed that he lived in then, and his eyes were half open. I started singing "Danny Boy" to him very softly, hoping I might see something ignite in his eyes. I didn't, although I did notice the corners of his mouth turn up slightly. But I once again had to grab onto my faith that, deep inside him, he was remembering, and singing along with me.

When I was about eight or nine, I ran in from the backyard and found my father behind his desk writing on his note cards, and pulled him outside to the yard. I pointed up to the sky, where thick gray clouds were bumping into each other and a shaft of sunlight was splitting through like a spotlight. "That's God looking through the clouds at us," I told him.

"Maybe," my father said, nodding and getting an amused look in his eyes. "But you know, God doesn't need a window through the clouds to see us. He's always watching over us."

There were times during the Alzheimer's years when I wondered if God was watching or if He had turned away. But with my father in some distant place and his days on the earth growing short, I reminded myself that faith is what you hold onto for dear life when there aren't any signs or whispers, when things seem bleak and you feel yourself edging toward despair.

It was a lonely decade for me, in part because my family was so disjointed, I didn't have the constant embrace around me that strongly bonded families do. The memories from my childhood, when my father talked to me about God always being present, always listening and watching, were what pulled me back from despair. They had imprinted themselves on me, and in many ways they became my lifeline.

Alzheimer's is a clever thief. It steals a person in so many different ways. Sometimes you're surprised by the absence that confronts you. Sometimes you're taken aback by what has moved into that absence, what has replaced the person you knew. This is particularly true if the person with Alzheimer's turns into a younger version of themselves — someone you never knew — or if long-buried personality traits rise to the surface.

You might find yourself constantly thinking you did not see this coming. I think the salve for the wounds that open up is the knowledge that you are getting to know your loved one in ways you might never have before. Of course, that can either be a good thing or a bad thing. But I believe strongly that curiosity can dull the edges of the pain you're feeling.

I often wished my father hadn't slipped into silence. That wish was resurrected when I started the support group Beyond Alzheimer's and heard so many stories about the personality transformations of people's loved ones, and how they got to see facets of them that had been hidden. I will always wonder what I might have learned about my father if he hadn't drifted so far away, if he hadn't settled in a place where he apparently didn't need a voice.

So much changed in the years of his illness — both within me and between the two of us. There was a tranquility, even a familiarity and a comfort level, that had not been present before. But in the deepest places, he remained a mystery. Maybe in some way that was his victory over Alzheimer's, that even an overpowering disease couldn't breach the walls of the citadel where he kept much of himself hidden.

As a young girl, I rode behind him on horseback, wondering what he was thinking, what was going through his mind as his eyes roamed over hillsides and fields. As a grown woman, I sat at his bedside wondering many of the same things — where was he? Where had the wanderings of his soul taken him? He left me with both gifts and mysteries, and I have to find contentment with that.

Excerpted from "Floating in the Deep End: How Caregivers Can See Beyond Alzheimer's." Copyright (c) 2021 by Patti Davis. Used with permission of the publisher, Liveright Publishing Corporation, a division of W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.

Read More