How Art Can Help Heal

A cancer survivor and artist finds peace in the meditative practice of ikebana

When you meet Tisha Kenny — vibrant and enthusiastic — you’d never believe she’s a cancer survivor, not to mention a three-time survivor of breast cancer in her 30s.

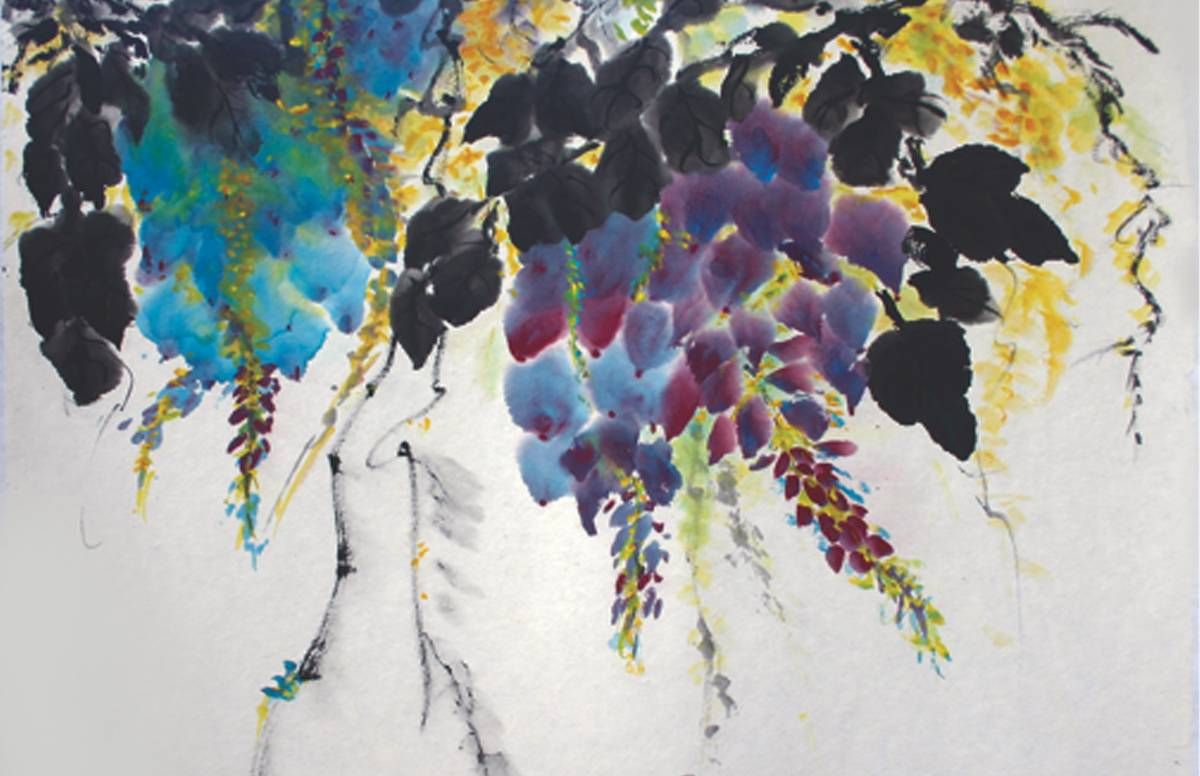

“I never thought I’d see 40,” says Kenny, 74, a San Francisco artist who’s a retired nurse and co-founder of an art/health nonprofit. Her passion is flowers. Her art features both delicate Chinese brush-style watercolors on rice paper of flowers, like the iris, lotus and peony, and Impressionist-influenced landscapes: two very different styles.

“Impressionism for me is freedom with color and the unfolding of a painting as a journey on a canvas. Brush painting is structure,” she says.

So is ikebana, the Japanese art of flower arranging, which she’s studied for over 30 years in San Francisco. Kenny is a student of the oldest style, Ikebana Ikenobo, founded in the 15th century in Kyoto, Japan by monks, a complex art underpinned by Buddhism thought.

Watching Kenny create an ikebana display is like a meditation, a serene lesson in restraint, form and less-is-more, a startling contrast to the profuse bouquets you often see at florist shops and on event tables.

"I made a commitment to art to apply to my own healing and my work in the health care field."

In 2017, she self-published a book about the significant roles of art, ikebana and writing in her healing process, Shifting Branches/Shifting Thought: Ikebana and the Art of Healing. Her book also recounts how she used what she learned at the San Francisco nonprofit she co-founded, Health and Human Resource Education Center.

Art and Illness

Kenny's art has changed over time; before, during and after her cancer. As an intensive care unit nurse in San Francisco and later a nurse practitioner at the Asian Women’s Health Center in Chinatown and at Planned Parenthood, Kenny always took art classes. She created art notecards from her watercolors, which three local stores carried.

But she began studying ikebana during her breast cancer bouts in her 30s, which ended with a double mastectomy. Though she often didn’t feel like it, Kenny resolved to attend an ikebana class every Monday, regardless of how she was feeling that day.

“I made a commitment to art to apply to my own healing and my work in the health care field. If you're committed, you have to make time for it," says Kenny, an Irish-American whose voice still retains traces of her native Rhode Island, though she came to San Francisco during the Summer of Love in 1967 (and never left).

Perhaps ikebana is linked to longevity: she studied until her teacher, a Japanese woman, retired at age 95. Her new teacher is, relatively speaking, a spring chicken at 88.

Revealing Emotions Through Art

Two art-health programs in the breast cancer community helped her enormously, Kenny says. The Healing Legacies Project invited women with breast cancer to submit art about their experience — anything from sculpture to quilts to writing to performance pieces to photographs — which appeared with a short bio of the woman and her artistic process. Kenny wrote about her personal experience with cancer for the project, founded by the Breast Cancer Action Group in 1993.

Another artist submitted a self-portrait wearing an evening gown, cut to reveal her mastectomy scar — a controversial photograph that ended up on the cover of The New York Times Magazine in 1993, and elicited one of the biggest responses to anything ever published in the newspaper. Artist Matuschka, then 39, was giving out posters and postcards in public of her dramatic self-portrait, which grabbed the attention of the magazine’s female art director.

At Art.Rage.Us, a project that asked artists and writers nationwide to contribute to an exhibit at the San Francisco Main Library Gallery, launched by the Breast Cancer Fund and local chapters of the American Cancer Society and Susan G. Komen Breast Cancer Foundation, Kenny was on the founding committee. The exhibit later toured the nation, and resulted in a powerful 1998 book, Art.Rage.Us.; Art and Writing by Women with Breast Cancer, where 75 women express, and transcend, their emotions about cancer in fiction, nonfiction, art, photography and mixed media.

Music of many types, from nature sounds of the sea and rain to meditative music that promoted relaxation, also helped Kenny heal. “I took it to the hospital with me, and listened to it when I was going to sleep and when I needed to relax in making decisions,” she says.

Validating the Role of Art

After getting a master’s degree in public health from University of California at Berkeley, Kenny ran graduate health services administration programs at Antioch University West in San Francisco, an outgrowth of Antioch College in Ohio, founded by abolitionist and education reformer Horace Mann. In 1984, she co-founded, and became executive director, of Health and Human Resources Education Center in Oakland.

The center developed a Health Through Art program, where art was used for healing in social issues like drug and alcohol addiction, violence prevention and racism.

“My mission is to validate the role of art in personal and social healing,” Kenny says.

Longtime Health Through Art board member Adriana Diaz, who’s taught creative meditation worldwide, wrote Freeing the Creative Spirit Within, a guide to releasing your inner artist through exercises and spiritual practices.

“A student with cancer told me one of the exercises in the book, drawing mandalas, helped her more than anti-nausea medications she was taking. ‘I forgot I was nauseous,’ she said,” says Diaz, who currently teaches art classes at senior centers in the Bay Area.

"Art is an experience of going deep within you, and going to where your pain is."

Anna Halprin, the well-known postmodern dancer, once took a workshop where everyone was told to draw pictures of their bodies, Diaz adds. Halprin drew an object shaped like a pinto bean in her lower abdomen. After she went for tests, she was diagnosed with a tumor in that very spot.

“She found her own cancer; it was like her body talked to her. Maybe she had sensations in that spot and drew it unconsciously,” Diaz says.

It seems her art keeps her young: today, Halprin is 99.

'A Balance of Left and Right Brain'

After Kenny retired at 65 from her nonprofit, she kicked her painting career into high gear. She joined Etsy to sell her work online, and began actively pursuing galleries for exhibits.

Kenny's art has been exhibited all over the Bay Area, including, from 2011-2019, at Art Span Open Studios where over 800 artists in San Francisco showcase their work each October (different neighborhoods are featured each weekend). Galleries from Grey City Gallery to City Art Gallery, the Hotel Triton, restaurants like Crepe on Cole and health centers have exhibited her paintings and notecards. Filoli, a historic century-old house and garden in the South Bay, as well as the Ikebana Ikenobo San Francisco headquarters, have displayed her flower arrangements.

Why does art hold such a special place in Kenny's heart? “Art is so therapeutic. From expressing your creativity in creating visual arts, to seeing it in hospital and health environments, to journaling, it touches a place you don’t get to otherwise,” she says. “Art is an experience of going deep within you, and going to where your pain is. It’s a balance of left and right brain."

Read More