How Mental Health Stigma Shapes Lives

Psychologist Stephen P. Hinshaw revealed his family secrets in a 2017 memoir, where he described how his father’s misdiagnosed mental illness fueled his own career-long fight against stigma

I recently wrote "After 50 Years, I'm Not Keeping This Secret: I Have a Mental Illness" for Next Avenue about my experience living with bipolar disorder.

Knowing I wanted to learn more about the subject of stigma, I contacted Stephen P. Hinshaw, PhD, Distinguished Professor of Psychology at the University of California, Berkeley, where he was Department Chair from 2004 - 2011. He is also Professor of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at the University of California, San Francisco.

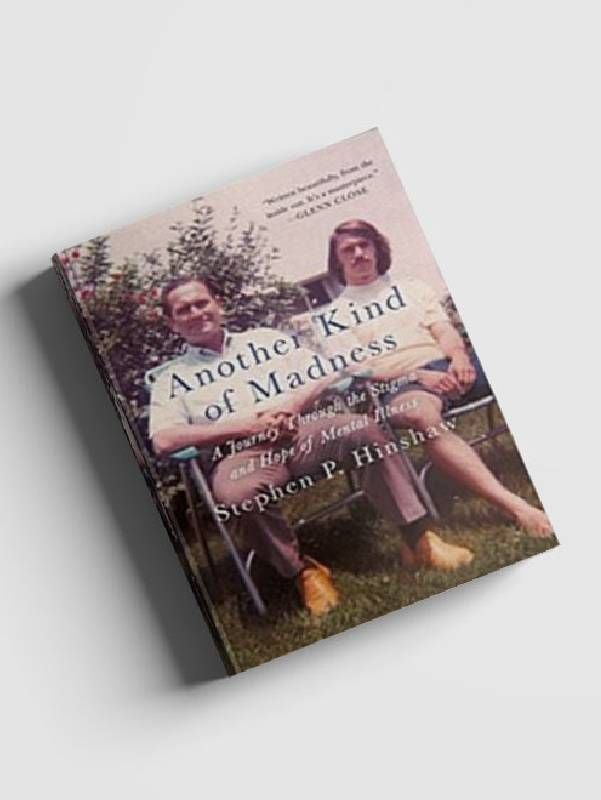

Hinshaw is the author of "Another Kind of Madness," a book he wrote about his family's mental health and how stigma made it infinitely worse.

This interview has been lightly edited and condensed.

Steve Mencher: Perhaps we should start off with a brief description of stigma as it applies to mental health.

Stephen P. Hinshaw: Stigma is a term, interestingly, of ancient Greek origins. It signified, millennia ago, a literal brand, a burn, on your skin to show to the general public that you're a member of an outcast group.

In the 1980s, people in many countries were literally branded if they were HIV-positive, given that HIV was a horribly stigmatized illness. If you were in a concentration camp in Germany or Poland in the 1930s or 40s, you would have numbers tattooed or burned into your left wrist, visible stigma. Such individuals included not only Jewish people but gay/lesbian individuals and those with mental or neurodevelopmental conditions.

"If we denied positions of leadership and empathy for everybody who had experienced major depression or bipolar disorder or PTSD or ADHD, that's a third of the population."

Today, it's more psychological, and too often applied to people with mental or neurodevelopmental disorders. We tend to stereotype such people. They're not very competent. Probably they're violent. We have prejudice. We don't really like them. They're threatening in some way.

And then we are highly likely to discriminate, which can mean denial of health care and basic human rights — and also being placed for centuries in snake-pit institutions or, before that, banished to the countryside. Today, since we've closed most of the psychiatric state facilities, discrimination means being left on the street without adequate support or services and being blamed for your predicament.

So, stigma is not just the sum of stereotypes, prejudice, discrimination. If I stigmatize you, you're not only a member of that outcast group, but you've also lost your individuality. And worse, maybe even your humanity. Stigma ultimately leads to dehumanization.

There's a chilling and dramatic scene in your memoir, "Another Kind of Madness," where psychologist and writer, Kay Redfield Jamison, who is one of my heroes, is teaching a class of young mental health professionals in training at UCLA. She asks whether they would end their pregnancies or that of their partners if it could be conclusively demonstrated through DNA testing that the fetuses contained a gene for manic-depressive illness. All but two members of the class raise their hands to indicate they would terminate the pregnancies.

Can you recount that scene for me and expand a bit upon what you felt at that moment, taking into account that you would have been erased from the world [because of your father's illness], as I would have been [because of my own diagnosis], if nobody with a gene for bipolar illness was ever born?

I thought, 'Don't you know my dad?' I mean, he struggled since he was 16 with being misdiagnosed [as schizophrenic] for 40 years. Almost dying in some of the country's worst mental hospitals. Spontaneously, miraculously in some ways, recovering from these terrible bipolar episodes he had, and he was a great dad and a great teacher and philosopher.

I thought, 'Don't you know that a person with lived experience of bipolar disorder is more than the symptoms and the impairments that they experience?' You don't know what it was like to have, when I was a kid, my dad disappear for month after month at a time, and never know where he was because his own doctor had said, 'If your children ever learn of your mental illness, they'll be permanently destroyed.'

Back in the 50s and 60s, the doctor's orders were, 'Mental illness is so toxic, you can't talk about it.' This is the ultimate stigma and silence and shame. We can't live this way as a society — everyone loses, economic productivity is lost and human potential is shattered.

I'm also someone with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder as your dad was, and I'm writing about my own experience with stigma, but I didn't really understand all the facets of it before I read your book. Tell me what self-stigma is.

Back in 1954, a famous social psychologist named Gordon Allport wrote a book called "The Nature of Prejudice." Now, stigma wasn't quite in the lexicon then, but he said pretty categorically, if society has a lot of prejudice and bigotry against a certain group, it's inevitable that members of that group will internalize it.

We know today that this was an exaggeration because members of stigmatized groups can overcome this internalized or self-stigma, especially through advocacy, bonding together with like members, and taking social action. Many members of so-called minoritized groups have higher self-esteem than the so-called majority, as a function of getting birds of a feather to flock together, demanding rights, and losing that isolation that's a big part of self-stigma.

Thinking about our conversation, I was trying to come up with things that stigma makes impossible for those of us diagnosed with mental illnesses. Of course, I always think of Thomas Eagleton in 1972 [Eagleton was forced to withdraw as a vice presidential candidate after it emerged he'd been treated for depression]. And I said to myself, oh well, I can't ever be vice president. And my wife has talked sometimes about joining the Peace Corps as senior volunteers and we've wondered if my mental health issues are disqualifying, although their website currently has no hard and fast restrictions on being bipolar.

A recent honor student of mine was denied entry into the Peace Corps because of a history of depression. I mean, this is in the two thousand twenties, right? If we denied positions of leadership and empathy for everybody who had experienced major depression or bipolar disorder or PTSD or ADHD, that's a third of the population. I mean, we're shooting ourselves in the foot. Do we have cures for bipolar disorder, severe depression, PTSD? No, but we have treatments that really aid and abet recovery. If you see your mental health care provider for support and treatment for your mental health condition, with medication as needed, you get better on average than seeing your physical doctor or your general practitioner for a physical health condition.

But the stereotype is 'once mentally ill, always mentally ill.' It's permanent, you're flawed. These are untruths.

I'm thinking about how society has blamed parents for their children's mental illness, an extension of stigma. And I'm remembering growing up in the late 1950s and early 60s and seeing a story on TV about monkeys in a laboratory where they are given a choice of a wire mother or a cloth mother after being taken from their real mother. And I wonder how that sort of research played into attitudes about mothers being responsible for their children's security and even their mental health.

I'm sighing, thinking of that research by psychologist Harry Harlow. Yes, attachment bonds are important, but in wildly inaccurate depictions, what was said to be the cause of autism, from 1938 when it was discovered, until the mid-70s. A refrigerator parent, so aloof and cold that not only did the child have an insecure attachment, but no attachment bonds altogether. But these old ideas of 'parenting is everything' die hard.

"So, access to treatment, recognition, family support, understanding the genetic liability to bipolar disorder and recognition that recovery is a real possibility — all these are key."

How did you develop schizophrenia? Well, you had a schizophrenogenic mother: cold, aloof, hostile, demanding. You couldn't really deal with that so you coped by developing an alternative reality, starting to hear voices and generate false beliefs. We now know that genes are the big determiner of autism spectrum, schizophrenia spectrum, bipolar spectrum conditions.

However, this doesn't take parents and families — and communities at large — off the hook. It might relieve some unnecessary blame and shame and guilt, but also how a family responds to the youngster, the teenager, the young adult with neurodivergence makes a big difference for outcome. We'd like the genetic perspective to absolve the blame, but not the responsibility for positive relationships at home, for developing strengths, and for the ability to get access to treatment.

Bipolar disorder when untreated, as you well know, can lead to strengths, but also about 35 to 40% of people with severe bipolar disorder attempt to end their lives. And about half of that number complete suicide, often when the energy of the mania and the despair of the depression come together in what we call a mixed episode.

So, access to treatment, recognition, family support, understanding the genetic liability to bipolar disorder and recognition that recovery is a real possibility — all these are key.

And who are some of the most successful people in just about every society we know? It's the first and second degree relatives of people with bipolar disorder. They have some of the genetic liability, some of the 'juice' if you will, but lacking the despairing depressions or the psychotic manias. This is why bipolar disorder has not faded out of our gene pool, because it can be adaptive if it shows up with 'low doses.'

Finally, as we finish, what positive changes have you seen in relation to stigma and what changes still need to be made?

I am co-chair of the scientific advisory council of Bring Change 2 Mind, Glenn Close's anti-stigma organization, with Bernice Pescosolido, the noted sociologist from Indiana University, who runs the National Stigma Study. This study has been going on for decade after decade. Interestingly, since the 1950s, the same vignettes and questions have been used to try to track trends in the public's attitudes about people with mental illness.

Two years ago, Pescosolido published a study with her team showing that for the first time in modern history, the U.S. public actually is more accepting of depression — not desiring as much social distance. It's pretty clear that athletes, celebrities, the good part of social media and the like, have lifted depression out of some of the accompanying shame and stigma. But, in the same study, stigma against addiction/substance abuse, as well as schizophrenia, increased during the two thousand teens.

So, there's a long way to go. We're still threatened by the 'choice' that the addict puts the stuff in their veins, or their mouth, or their nose. And the stereotype of schizophrenia as irrational and violent all the time is scary and threatening.

What's the public face of mental illness in the United States? Images of young men in their 20s, strange looking, who are school shooters. Incompetence and violence are still the number one media stories.

We've got a long way to go, Steve. What's needed are improved and accurate media coverage, enlightened policies, funding for community programs and treatment — and above all, humanization.