How My Dad's Letters of Gratitude Overcame Death

Research shows, and his letters proved, that writing letters of gratitude builds stronger positive emotions and elation

During my dad's 12-year battle with Alzheimer's, I witnessed his mind roam away, slowly, until his body gave way, shutting down too. His departure was torture.

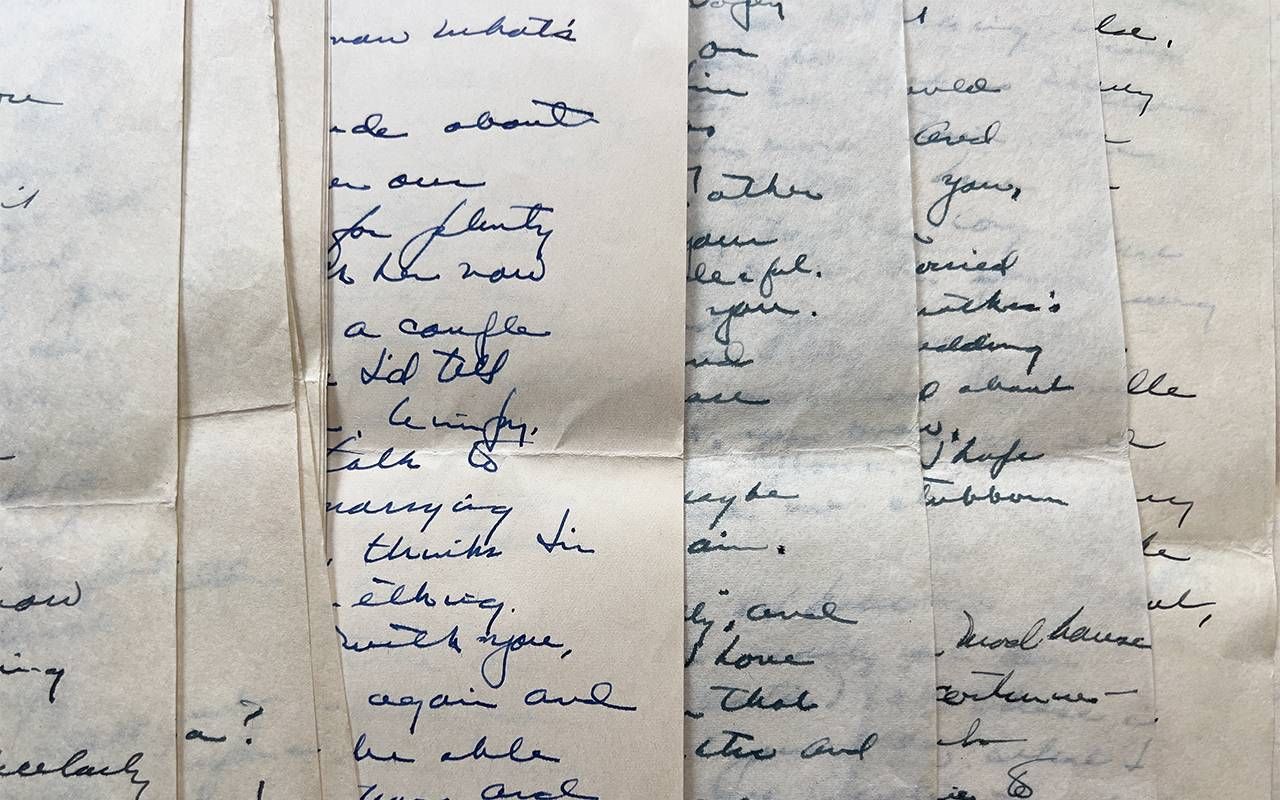

Yet he left me with more than the devastation of a disease that steals words, memories and years of life. Behind him remained sentiments of gratitude in letters, emails and poems that encapsulated the best of his spirit over decades.

He left joyous descriptions of his dad, his fox terrier Harry, my mom, his ceramic sculpture making, his sailing and his beloved views on nature. Some of my dad's letters are written in ink via one of his many antique fountain pens that now sit on my desk. Other messages from Dad are digitized.

When I read his words, an ethereal voice wakens.

One he sent me in 2013 a couple of years after his Alzheimer's diagnosis says, "My new fascination with cloud formations is refreshing. They are right over my head, and yet I have hardly noticed them. Sometimes they are dull, but often they are very dramatic. It's a free show!"

When I read his words, an ethereal voice wakens, flickering on my screen or in the semi-permanent loops and flows still breathing on the pours of paper. These words stay with me when I swim in the lake near my home in Switzerland, heart up, tracking cloud shapes I want to store in my mind. My dad's messages grip gratitude that clings to me, replacing less happy memories I let disintegrate.

I used to pull away from hugging him. I stopped wanting to swim with him as a child. I didn't often hold his smooth fingers, because, as I grew up I became afraid of his moods, intensity, and irritability. He wasn't an easy person to grasp, yet those same hands of his left crumbs of a soul beyond depression, work stress, and the misuse of alcohol.

He Wanted to Encourage Me

"Dear Amy … I want to visit you at Syracuse," he wrote when I was still getting my bachelor's degree. He was concerned I'd be disappointed by his business trip to North Carolina that would interfere with Parents Weekend in New York.

As an advertising exec, his letters to me didn't highlight his back-stabbing clients and the weight of his role working as the CEO for a business built on making objects and services appear worthy of love. Instead, he shared what he loved about his work, details he scribbled down because I was studying for a career in his industry. His note on an LA hotel stationary described a live TV commercial he knew I'd find cool. He wanted to encourage me.

His tone was Seussical, infused with joy. His letterforms rippled like Lake Michigan, Newport Harbor and the Intercoastal Waterways where he sailed.

When my oldest sister was born in 1967, my dad, an American naval officer, was stuck overseas. He sent my mom a letter that captured his young voice. It reads, " ... it's such an important thing (referring to his new baby girl) that it doesn't seem like anyone in the world, let alone on this ship, is worthy of being the first to know."

Further on he wrote, "I've decided I won't tell anyone! I'll keep it all to myself (referring to the birth of my sister) and hoard the pictures, letters, tapes and everything, especially thoughts, up in my bunk."

Years later, in a long letter written to my oldest sister's newborn son, he began with, "You were born today!" His tone was Seussical, infused with joy. His letterforms rippled like Lake Michigan, Newport Harbor and the Intercoastal Waterways where he sailed with my sisters, my mom and his grandchildren. He wrote my nephew about every trivial yet wonderful thing that was happening the day he was born, just so one day my nephew would know his significance.

What His Letters Proved

My dad struggled to connect off the page. He fought a sense, I observed, of never achieving enough, at least according to his own impossible standards. But his letters proved the existence of a guy who, if given the time to reflect, could find treasures even while suffering the isolation of a neurological disease.

It seems he instinctively knew that the act, not just the feeling, of being grateful alters the brain, impacting mental health, especially if that gratitude is recorded and gifted to others. Research shows that writing letters of gratitude builds stronger positive emotions and elation than writing gratitude lists, journaling, or reflecting on positive things. Research on holocaust survivors showed that neural correlates to gratitude, in the brains of those living in concentration camps, could be linked to the survival of the victims.

Research shows that writing letters of gratitude builds stronger positive emotions and elation.

If it's so simple to write a short letter with a handful of grateful phrases, then why don't we write more letters? Why do many of us never find the time? According to a paper by Amit Kumar, assistant professor of psychology at University of Texas, Austin, we miscalibrate.

We underestimate the impact of "prosociality" and how a letter of gratitude will impact a recipient. We may become overly concerned with word choice and the quality of writing. Yet Kumar explains, " ... what may matter most to recipients is that gratitude is expressed at all." Kumar goes on to quote George Saunders, a professor from my alma mater who said at a Syracuse University convocation speech, "What I regret most in my life are failures of kindness."

There's still time for all of us to leave letters with thankful details embedded in them like my dad did. My new writing practice involves deploying the fountain pen my mom and dad engraved with my name when I was a teen or the one my husband gifted me, depending on the day.

There's still time for all of us to leave letters with thankful details embedded in them like my dad did.

I can record a detail of that sunrise. I can share the name of the novel I started or that gladiola that bloomed this morning. I can place a stamp on a letter or postcard before I forget. I can shuffle to the post box, and slip my words inside the hollow space where words, or the minds they come from, move on connecting to others, maybe forever.

One of the last stanzas of my dad's poem "My Head Held Back" in his chapbook "Rhyme and Reason" reads:

The balance and rhythm of flying

comes naturally, like riding a bicycle.

But the details that keep you alive

come slowly from study and practice.

My dad was right. His study and practice of using words survived decades. They traveled oceans. His words sent to others outlasted alcoholism, depression, Alzheimer's and even death.

I see many of the best details of him still there on the page or sometimes in the clouds. I can only hope to follow him, leaving behind the most fascinating traces of what I've been given.