How This NPR Host Became an Advocate for Assisted Suicide

A talk with Diane Rehm about her book, 'On My Own'

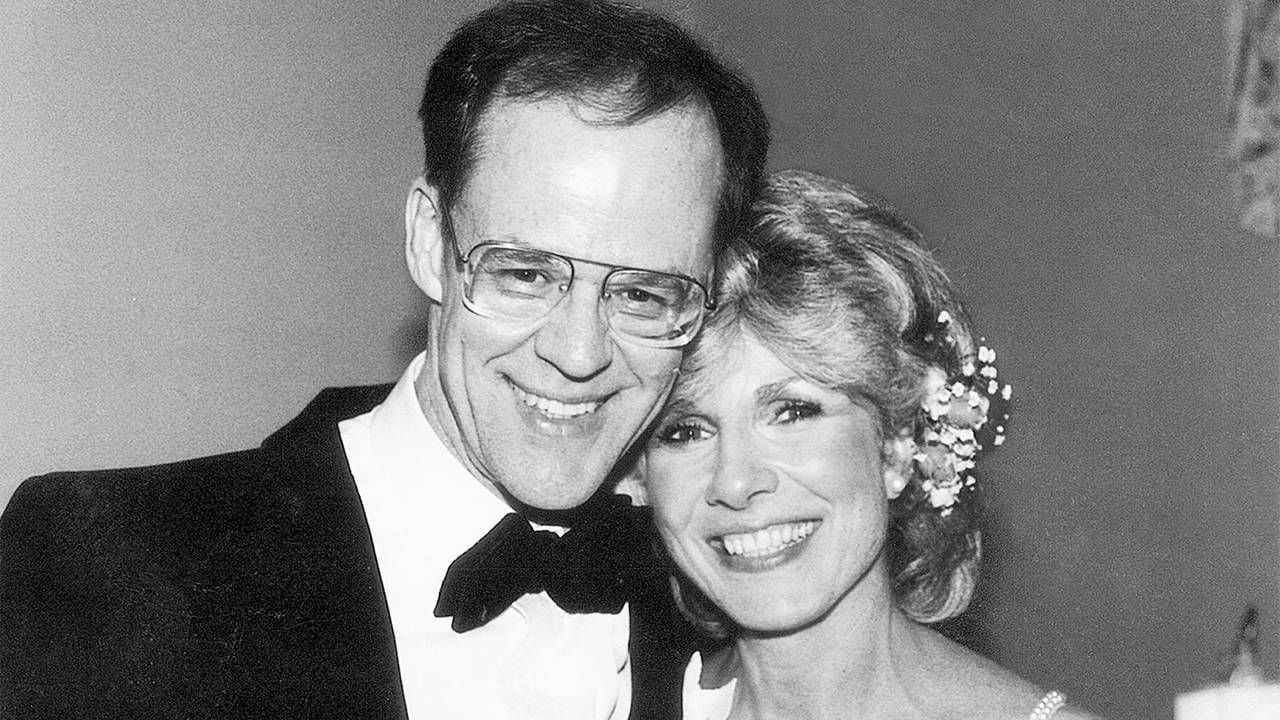

When Washington attorney John Rehm was walking with his wife, NPR talk-show host Diane Rehm, in 2005, she noticed a different sound in his footfall, a shuffle. It was the first sign their lives would never be the same. John Rehm would soon be diagnosed with Parkinson's disease.

As his condition worsened, the couple made the decision that John would be cared for at an assisted living facility in nearby Maryland. By June 2014, when he was no longer able to use his hands, arms or legs and couldn't stand, bathe or eat by himself, John told Diane he was ready to die. But when he asked for a lethal dose of medication, his doctor refused. Maryland is not among the four states (Oregon, Washington, Vermont and California — as well as a county in New Mexico) that allows doctors to assist their terminally ill patients to end their lives.

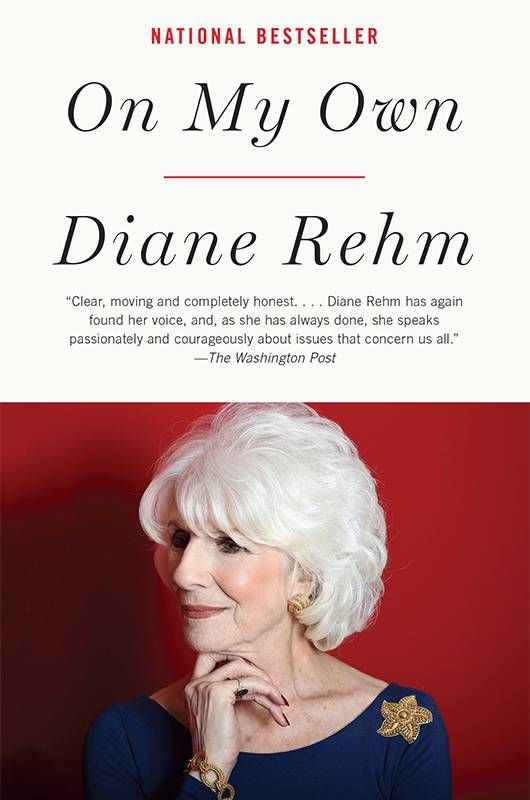

'On My Own' Tells Their Story

As Diane Rehm recounts in her book, "On My Own," her husband of 54 years had just made life's "ultimate decision," and it was thwarted. Still determined to die, John Rehm spent his last 10 days refusing all food, water and medications. He died of dehydration.

"We don't let our little animals suffer and people shouldn't have to suffer" if they choose to die, Diane Rehm railed at the time. That searing experience thrust the now-retired award-winning public radio host, known for moderating debates on controversial issues, into an unaccustomed role: as an advocate on one side of this country's right-to-die divide.

She and I have been friends for more than 30 years, and we spoke recently in her office at WAMU, the Washington, D.C. NPR station where she once originated her national broadcast (Rehm retired at the end of 2016) about her husband and her new mission:

Next Avenue: Before John was diagnosed with Parkinson's, how much did you know about the right-to-die movement and did you have strong feelings one way or the other?

Diane Rehm: Long before. John and I had both gotten a book from the Hemlock Society because we had talked about our deaths even in our forties and fifties when we were both healthy. We felt it was very important to think about death as a part of living. So as you plan your finances, you plan how you're going to exit this life. Neither one of us wanted to go into long-term care. Neither one of us wanted to suffer a long illness and we told each other that.

Based on your parents' experiences?

Absolutely. John's mother had taken her own life at age ninety-two. His father had taken his own life at age seventy-two. My mother died when I was nineteen and she was forty-nine. My father died eleven months later, truly of a broken heart. So I think deaths form us just as life forms us.

Was John's illness and his inability to get his doctor to prescribe the lethal dose of medication the wake-up call you needed about the issue?

Not the wake-up call, Richard. I wondered all along how long John was going to put up with his situation, because there were a few times even before he lost the use of his hands when he could still feed himself when he said, 'I don't know what the use of this is,' sitting in the bed. And I just listened. But (when) he got to the point where he could no longer do anything for himself, he said out loud, 'I am ready to die.' That was it.

As an accomplished lawyer, what gave John the notion that his doctor would be able to legally grant his wish and prescribe the lethal medication? He must have been aware that was not legal in most states, including Maryland, where you and he lived.

He knew full well that that was not legal in most states, but you have to understand along with Parkinson's comes a certain lack of logical thinking. So when he said, 'I feel betrayed,' which he did say so strongly, I think he was truly thinking that this doctor would help him die, a doctor with whom he had a relationship. And the doctor was sympathetic, saying, 'I don't blame you for wanting this. I understand, but I can do nothing.'

The one thing you did when you hosted several broadcasts on this issue is to have people on both sides: Barbara Coombs Lee of Compassion & Choices (who helped write Oregon's first-in-the-nation aid in dying laws); Dr. Ira Byock, the palliative care specialist, who argues against doctor-assisted dying because he says it distracts from the real issue — improving end of life care and Dr. Atul Gawande, another respected physician who wrote "Being Mortal," who has also not signed on to the campaign. The American Medical Association is also against it, saying it's antithetical to the doctor's role as healer.

But in California, the California Medical Association said we will not oppose this legislation, which passed, and where California goes, so may go the nation. (The law took effect in June, 2016.)

Do you think there are merits to the other side; do you respect their arguments?

I totally understand their arguments. That's why my argument is simply not that you should do this, but I should have the right to choose. That's my argument. There may be millions who say I want to live as long as possible, just keep me comfortable. Ira Byock is absolutely right to provide that kind of palliative care for those who want it. I don't want it for me. That's what I'm arguing for. I should have the right to choose.

I read recently that a thirtysomething Marine Corps vet was given four months to live 20 months ago. He was diagnosed with brain cancer and he argues if he had legal access to lethal drugs in the first dark days after the initial diagnosis, he might not be alive today. He got a second and third opinion and ultimately found a doctor who removed a majority of the malignant brain tumor. Today, his cancer is in remission. This points up that medicine is not an exact science and with the choice you're advocating, people could take their life when they don't need to.

On the other hand, that Marine, God love him, went and got several other opinions. He was not ready to say immediately, I'm done. He said, 'I want to find out whether this is truly the case or not.' I would do the same thing. I would check and check and check. But if after checking and checking and checking, the only thing that was going to matter was to keep me comfortable, then I'd be ready to go.

There's a debate in the right-to-die community about calling this 'assisted suicide' or 'aid in dying.' The term you use in the book was 'an act of relinquishment.'

Absolutely. It means letting go of life. That's what John wanted to do. His book was titled, 'Onward Journey,' and he really believed that we are so caught in the midst of this so-called reality that we don't fully understand or apprehend the other dimensions of what our reality may be. And I think he really did believe he was going on to a new journey.

You're pretty tough on yourself in the book, expressing guilt about not giving up your career to stay home to care for John. Was the choice really that stark? Because you describe the incident where John fell in the bathroom and how difficult it was for you to lift him back up. And you said you wouldn't have been much of a caregiver. Knowing all that, why are you wracked by guilt about this?

Because we took vows. I think at the end, our decision to place him in that facility was to my mind a relinquishment of my vow. Everybody who walked into his room said, 'Oh my God, how beautiful.' Because we had taken the same fabric from the drapes in his bedroom to create a warm environment. He loved it. (Yet) turning John over to someone else's care really did make me feel guilty. People are thinking, 'So, Diane you've had this great career, you've done all this stuff, talked to all these wonderful people, maybe now you ought to just go and stay home with him?' I think I just couldn't do it. I wasn't ready to give up [my career]. It was both the difficulty of giving this up and the difficulty of becoming a caregiver. I was afraid I'd end up resenting him and his illness rather than being the loving, wonderful wife that some fairy tales have us being.

If the situation were reversed and it was you who he had to worry about, would you go willingly to a nursing home or beg to stay at home?

I would have stayed at home and I probably would have taken my own life. I'm never going into a facility. Not ever. As nice as they may be. I was surprised that he agreed to go because we both said, 'Who wants to go there?'

In some ways, the title 'On My Own' is not completely accurate, I would suggest, based on your own writing where you say you still talk with John, he's always with you.

Absolutely.

So you're really not on your own?

I talk with him every single day. I talk with him privately. I talk with him when I'm sitting in the studio while I'm recording and looking out the window. And I talked with him this morning. I was leaving the apartment and leaving my dog, Maxie, and I said, 'Maxie, Brian's coming to pick up this check but Daddy's here with you.'