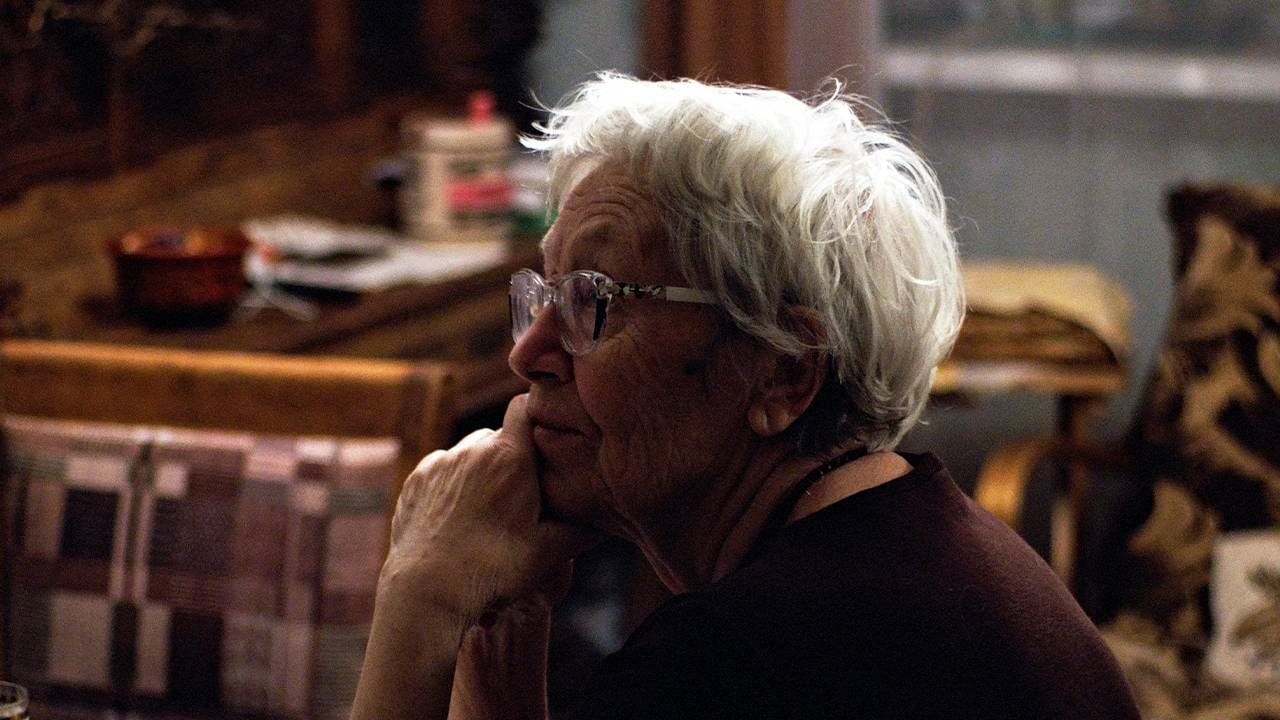

How To Tell If Your Parent is Suffering from Depression

Feeling unhappy is not a normal part of aging. Here are some signs of depression to watch for, and ways to offer help.

I didn't have much contact with older people when I was young. Much of what I thought I knew about them came from movies and TV, which often portrayed them as doddering, infirm, and/or clueless. Getting older, I concluded, was a sad time of life, and the people who had to go through it—somehow this did not include me, as I would be young forever—must be so depressed.

And then a funny thing happened: I got older. And instead of getting depressed, I got happier. I worried less about the future. I took up pickleball and cultivated new friends. I figured out how to appreciate the present. I felt less pressure to become something amazing. In short, I relaxed, and when I did, the world seemed less threatening, and more amazing itself.

Depression and anxiety are as much a cause for concern in older people as in younger people.

Of course, not everyone feels less depressed or anxious as the years go by. Things happen—accidents, illness, loss, all of which can throw us for a loop—but the assumption that, as people age, they naturally become more depressed and anxious, is not borne out by research.

In fact, the National Institute on Aging (NIA) reports that the later years are often an especially contented time, as there is freedom from child-raising responsibilities and the confines of work, as well as (hopefully) a comfortable level of financial security.

So when depression and/or anxiety do arise in older adults, it's not fair to assume it's "just aging." Depression and anxiety aren't the norm, and they are as much a cause for concern in older people as in younger people.

How Signs of Depression and Anxiety Can Be Missed

"We tend to end life the way we begin it. When we are little, emotional problems often show up somatically (physically), which holds true for older adults," said Maximilian Fuhrmann, clinical psychologist with a specialty in geropsychology, and co-author of "Pandemic Schmandemic," which discusses the point that depression is not part of aging and that the young have been more depressed and suicide rates corroborate this, during the pandemic.

"When seniors feel bad, they typically go see their medical doctor. Rather than explain that they are depressed or anxious (which they themselves may not recognize as such), they complain instead of lack of energy or motivation, which prompts their MD to run a series of medical tests. It's rare that their MD thinks to refer for them for a mental health workup," said Fuhrmann. But often that's exactly what's needed.

The NIA points out that the somatic symptoms of depression can differ across people and across cultures. In some cultures, depression may manifest as generalized or specific aches, pains, headaches, cramps, or digestive problems, while in others, fatigue and lethargy are more typical markers of depression.

Contributing to the problem of getting an accurate diagnosis is the fact that older adults often buy into the myth that feeling bad is a "normal" part of aging. Insomnia is a prime example, according to Fuhrmann.

"Longstanding insomnia alone can contribute to the development of depression and anxiety," he said. "It can exacerbate already existing mental health problems, or it can be a symptom of an underlying emotional problem. But because we've "normalized" insomnia, we fail to recognize when it is a sign of something deeper."

Too, certain medications or medication interactions can also give rise to sudden or gradual emotional changes, while too high a dosage of certain medications can contribute to lethargy, depression, cognitive problems, and agitation. And according to the NIA, depression is not uncommon in people suffering with Alzheimer's and related dementias

"Dementia can cause some of the same symptoms as depression, and depression can be an early warning sign of possible dementia," the agency reports. While certain mental illnesses tend to soften over time, there is evidence to suggest that people who experienced depression and/or anxiety as a young adult are more likely to experience them again as an older adult.

What Are the Causes for Concern?

Emotional problems should always be taken seriously, whether in the young or in older adults. With the older population, however, there are specific risk factors associated with depression and anxiety, especially when there is compromised immunity. Older adults who are struggling emotionally often don't heal as quickly or as completely from cancers, infections, and other illnesses.

Suicide is also a concern.

"The second highest rate of suicide is in elderly white men," said Fuhrmann. Loss of status and/or income, the loss of a spouse, a troubling diagnosis such as a terminal illness or dementia, or the sudden transition to living alone can drive up the suicide risk factor.

Challenges After the Holiday Season

For many older adults, the days, weeks and months following the holidays can be particularly difficult. The sudden plunge back into a quiet routine, or into isolation, can be a recipe for depression and anxiety, or, if depression and anxiety are already present, can exacerbate things.

But, said Fuhrmann, sometimes it's the holidays themselves—getting together with adult children and noisy grandkids, in a setting where they may not be comfortable—that can actually be more stressful.

Often older adults feel excluded in large groups, especially if they can't hear well, or if people are flitting around and ignoring them. After decades of holiday celebrations, some may feel the holidays are more of a burden than a joy. Fuhrmann suggests that sometimes it can be better if adult children go to their home instead, rather than bringing grandma or grandpa to their noisy home, or if that's too stressful, visit in smaller groups.

Encouraging the older adults in your life to talk about how they feel shows them you care, and allows you to keep your finger on the pulse of their emotional state.

"For some seniors, being visited alone is the best gift," says Fuhrmann.

But for those loved ones who feel at a loss after the holidays, helping them transition back to a quiet life is essential. Schedule regular visits during the first few weeks of January and February so that there is not a sudden plunge into isolation. If you live far away, even more frequent phone calls can help ease the transition.

If they are interested, schedule activities for them that begin immediately after the holidays, for example at their local senior center (if COVID-19 protocols are in place), and be sure they have a way to get there.

Encouraging the older adults in your life to talk about how they feel shows them you care, and allows you to keep your finger on the pulse of their emotional state. If you see new or worsening symptoms—anxiety, insomnia or hypersomnia (sleeping too much), loss of appetite, loss of interest in previous activities, vague physical complaints, or a worsening of existing physical ailments, it's time to call in a mental health professional.

Be Wary of Making Assumptions

It's time to challenge our myths about aging. It isn't true that people become depressed and anxious as a normal course of events as they age. Insomnia and hypersomnia (excessive sleeping) are not inevitable as we age.

It's true that individuals who suffered with emotional problems as young adults are more likely to suffer them as an older adults. But what's also true is that those who have had depression and anxiety in their young lives may be better able to cope with it as an older adult than someone for whom depression and anxiety come on "out of the blue."

The bottom line is that everyone is different, and making broad, general assumptions about what aging looks like and feels like is oversimplifying the matter, and potentially harmful to those we care about.

Where to Look for Local Resources

- Geriatricians (medical doctors who have additional training in the issues facing those age sixty-five and up) can be very helpful. You can get an online consultation with a geriatrician through university medical schools that have a department of geriatrics.

- Mental health facilities exist in most areas. Ask if there is someone on staff who deals in issues facing older adults.

- Your local senior center may be able to refer you to a gerontologist or therapist.

- Speak with your and/or your loved one's medical doctor about your concerns, and ask specifically about how to obtain a mental health workup. Don't be afraid to ask twice.

Listen to What Your Loved One Says

Don't forget that the older person you are concerned about has opinions, thoughts, and wishes all their own. It's important to listen to what they want and do not want, and to not assume that you know what's best.

It's always better to approach others in a spirit of camaraderie and teamwork rather than attempting to impose a course of evaluation or treatment without their input. It should go without saying, but always be respectful. You might think you know what's best for someone else—and you might even be right some of the time—but what's "right" might not be what's desired, and we all—regardless of our age—are entitled to be heard.

Read More