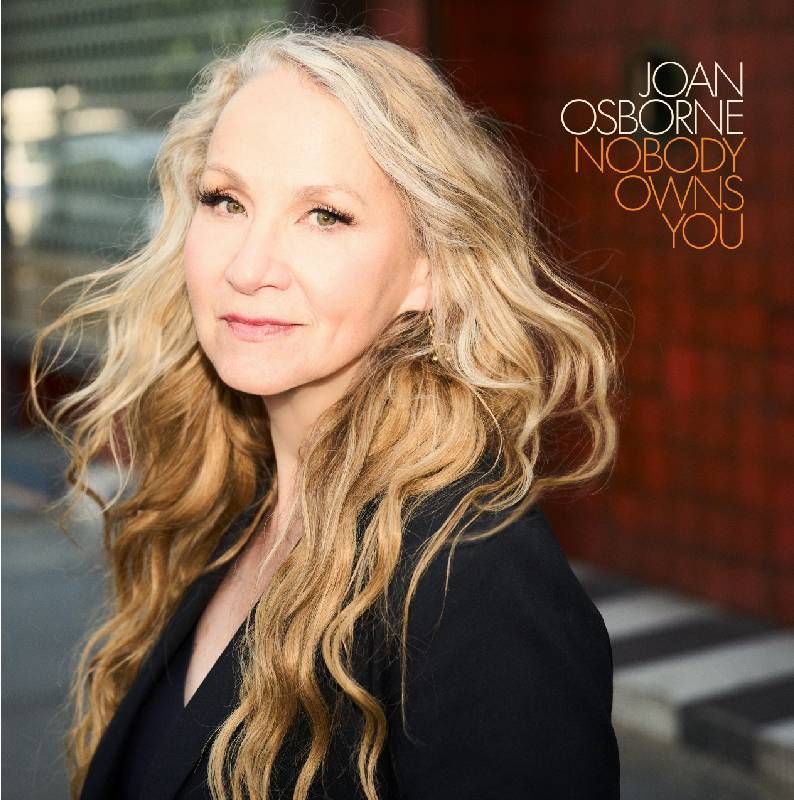

Joan Osborne on 'Nobody Owns You' — Her Most Personal Album Yet

The singer-songwriter behind 1995's hit "One of Us" discusses how the challenges in her personal life influenced her latest collection of songs

By the mid-1990s, singer-songwriter Joan Osborne had built a small but devoted following of fans, due in large part to her live performances as well as her debut album, "Soul Show: Live at Delta 88," which she'd released on her own indie label, Womanly Hips Records.

Then, in 1995, everything changed. Her first major label album, "Relish," was released, and its lead single, "One of Us," became an instant hit, garnering Osborne five Grammy Award nominations, including Best New Artist, Album of the Year and Record of the Year.

"It was," she tells Next Avenue, "the best of times and the worst of times." Though the major label deal, MTV videos, and seemingly overnight success had its benefits, including performances alongside Stevie Wonder and Luciano Pavarotti, a co-headlining spot on the 1997 Lilith Fair tour, and a musical guest spot on "Saturday Night Live," life in the spotlight wasn't a comfortable place for Osborne. In the years since the release of "Relish" she's put out 12 additional albums, none of which have reached the same level of commercial success — and that's perfectly okay with her.

"I feel like I've gotten to this place, and have been here for a while, that is pretty comfortable for me and that I like very much."

"Ironically," she says, "I've found that I have landed in this position, which was what I wanted back at the beginning — to have enough of a following and a fan base where I could continue to do the work that I am interested in without a bunch of people over my shoulder telling me, 'You gotta do this, you gotta do that.' And without that pressure of, 'We need the hit song.' I feel like I've gotten to this place, and have been here for a while, that is pretty comfortable for me and that I like very much."

Osborne recently spoke to Next Avenue about her newest album, "Nobody Owns You." An introspective collection of songs about love, loss and life's challenges, it is her most personal record yet. Over the course of a wide-ranging conversation, she discussed her discomfort with fame, her musical influences and the advice she'd give to her younger self.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Though you'd been touring and building a following for a few years, once the single "One of Us" was released it exploded and really changed the trajectory of your career. What was that period like for you?

On one hand, it was incredibly gratifying to have all the attention and all the praise and all the people saying good things about the record. It felt like people were responding to the record in an emotional way, and that it had meaning for them; it wasn't just like a booty shake song or something. It had a deeper impact, and that's what you want as an artist — you want your work to reach people. So that was wonderful.

It was a bit uncomfortable for me as a person, because I felt like I had found this place where I was more in control of my career, touring all around and doing shows, building a following and having my own band, and making decent money. But stepping into this other world of the photoshoots and the TV performances — just feeling so exposed like that. I mean, I didn't consider myself someone who looked or acted like a person that I would see on television, or a person that I would see in a magazine. That sort of mainstream success was nothing that I was looking for, and I felt like an alien in that world.

"I didn't consider myself someone who looked or acted like a person that I would see on television, or a person that I would see in a magazine."

I'm a private person, so it was weird to be recognized everywhere I went. I would go to the corner store and try to buy tampons, and people would be following me down the aisles. It was strange. I do have to acknowledge that without the success of that record, I probably would not have had that kind of big push which I'm still benefiting from today. But it was, just on a personal level, a bit like being forced to go back to junior high school again, dealing with all of that self-conscious stuff.

Your new album is deeply introspective. Can you share a bit about what's been going on in your life over the past few years, as you were writing and working on this collection of songs?

These songs are very personal. They come from a time that's been pretty turbulent in my personal life. My daughter is now grown and she's leaving for college, so there's that process of figuring out how to say goodbye to her and grieving her loss, but also being excited for her. My mother is beginning to show the unmistakable signs of Alzheimer's and dementia, which her older siblings had, and that is difficult, of course. I ended a 15-year romantic relationship, and that left me in a very raw place emotionally. And also, I turned 60 in 2022, so that's a moment where you take stock of your life and you think back about all the things that have happened to you. So it all comes from that perfect storm, if you will, of different things happening all at once.

According to the press release for the album, the title track was written as a message to your daughter. But as I was listening to it, I wondered how much of it was written as a message to yourself, that "nobody owns you."

Well, I think the reason I can say that to her is because I know it for myself, and if I am restating it for myself, too, then I think it's just because I've lived to understand that. I say this when I introduce it in a live setting — she has no interest in hearing anything that I am saying to her right now. [Laughs] She is not listening to any of my advice, my words of wisdom, that could make her life so much easier and save her so much trouble and suffering. Which is appropriate; what she needs to do now is separate from me. But I can put that in a song and then it's waiting for her whenever she is ready to listen. And in the meantime, anyone else who needs it can have it.

The song "Secret Wine," which you wrote about your mother, is heartbreaking. I watched my grandmother succumb to Alzheimer's, so I understand how devastating it is. What was it like for you to put those words to paper and record it for the album?

"Secret Wine" is a sort of prayer for [my mother]; if these things were being taken away from her, I pray that maybe there's something else that can arise in their place, that can be a comforting thing for her. In a way, it's like those Tibetan prayer wheels that every time you spin them, the prayer is said, whether you're speaking it or not. I put these thoughts and these hopes in a song and then every time it's played, either on somebody's stereo at home or me performing the song live, it's like spinning that prayer wheel and letting that prayer go out into the world. It's hard to do, but on the other hand, once you've faced those fears within yourself and tried to turn them into this positive hope, then the more people who hear it, the better. But it is scary to think about. I mean, you saw with your grandmother, it's frightening to see someone disappear in front of your eyes.

It's awful. If it's okay to ask, how are you doing with all of it?

My mother lives in Kentucky, and I haven't lived in Kentucky for a long time, so I definitely am wrestling with some guilt of having chosen to not be in the same city that she's in. Now that my daughter is going to college and I don't have to be around for her, I'm planning on spending more time in Kentucky to be with my mom. But we all carry that child within us, and it's disappointing to be in the presence of this person who always meant certain things to you and always could be certain things for you, and to seek that again and it's just gone. I mean, this isn't about me, it's about her. But that is a part of this that is hard — to seek something in someone that doesn't exist anymore.

"It's disappointing to be in the presence of this person who always meant certain things to you and always could be certain things for you, and to seek that again and it's just gone."

In addition to the personal songs, there are a few political ones, as well. The first single off the album is "Great American Cities." How did that track come about?

I travel a lot. And inevitably, I'll be sitting in some airport or bar or something, and there will be a TV playing and there will be these pundits who are running down American cities and saying all this stuff about, "They're crime ridden, they're dangerous." And I sit there and I'm like, "You are in your air conditioned studio, and you're gonna go from there to your air conditioned town car with the tinted windows and be driven by your chauffeur to your gated community. And you don't know these places, because you don't go there." I go there, and I see and understand that, yes, they have problems, but they're also full of the energy and joy and life that is a huge part of what America is. So that was my rebuttal to people who are running down American cities. I don't think they really know what they're talking about because I think they don't experience these cities in any but the most abstract way, because they never go there.

I read the essay you wrote for "No Depression" in 2020 in which you talked about Bob Dylan's influence on your last album, "Trouble and Strife." Were there any particular musicians that influenced this new album?

Yeah, absolutely. I was trying with this record to be direct and simple. I've written other songs that are more imagistic and sort of magical realism, and [with] this one, I just wanted to state very plainly what I was thinking and feeling. People who do that are people like Leonard Cohen, Lucinda Williams, [and] Hank Williams — people who are doing things in a very direct and simple way, and yet call forth very complicated emotions. We also listened to a lot of Feist. She's got these wonderful arrangement ideas and wonderful songs. She's a great singer; she was a real inspiration for this record. Also, Aimee Mann was a real inspiration for this record. You know, you're not necessarily stealing from people, but it's good to have this stew of different influences that you're playing at home and you're listening to on the subway or whatever, just to keep your mind in that place of, this is a way you can express yourself.

One of the things I've always loved about your albums is how different they all sound. "Trouble and Strife" has this AM radio kind of vibe, while this new album is more Americana. They all sound so different, even going all the way back to your first album. Do you go into a project with an idea of how you want it to sound? Or does it just organically happen?

I certainly have gone into the studio and said, "I want it to sound like this. I want this to be the sonic territory." And that will sometimes guide you. But sometimes the songs don't want to be that and they want to be something else. And if you listen to them, they will tell you what they want to be. That's something that I've learned, I think the hard way — that you have to listen to the songs instead of imposing your will on them. You have to allow them to blossom in the way that makes the most sense for them. So yes, you can say, "I want it to be an Americana record" or "I want it to be an R&B record," or whatever, and that can guide you. But you also have to let the songs be the ones that decide what they're going to be.

Given how personal this new album is, and all that you've had going on your life in the last few years, if you had to go back to the Joan of 1995, just before your career really took off, and impart some wisdom, what would you say?

[Long pause] I would say things that I probably knew even back then to be true: that you have to satisfy yourself before you can satisfy anyone else, and you have to drill down into the bedrock of your own self to get to the good stuff. You know, things that people will say that sounds cliché, but it's true. Write like no one's going to ever see or hear what you write because that's when you get to the good stuff. If you're worried about what this one or that one is going to think, or if you're worried about, "It's got to be a hit, it's got to be some artistic achievement," you're going to strangle the idea before it's ever born. So write like no one is ever going to hear or see what you do.

Read More