'Every Woman in Journalism Owes Barbara Walters a Debt'

A new book tells how the groundbreaking journalist was proud of her work and always pushing, but never content

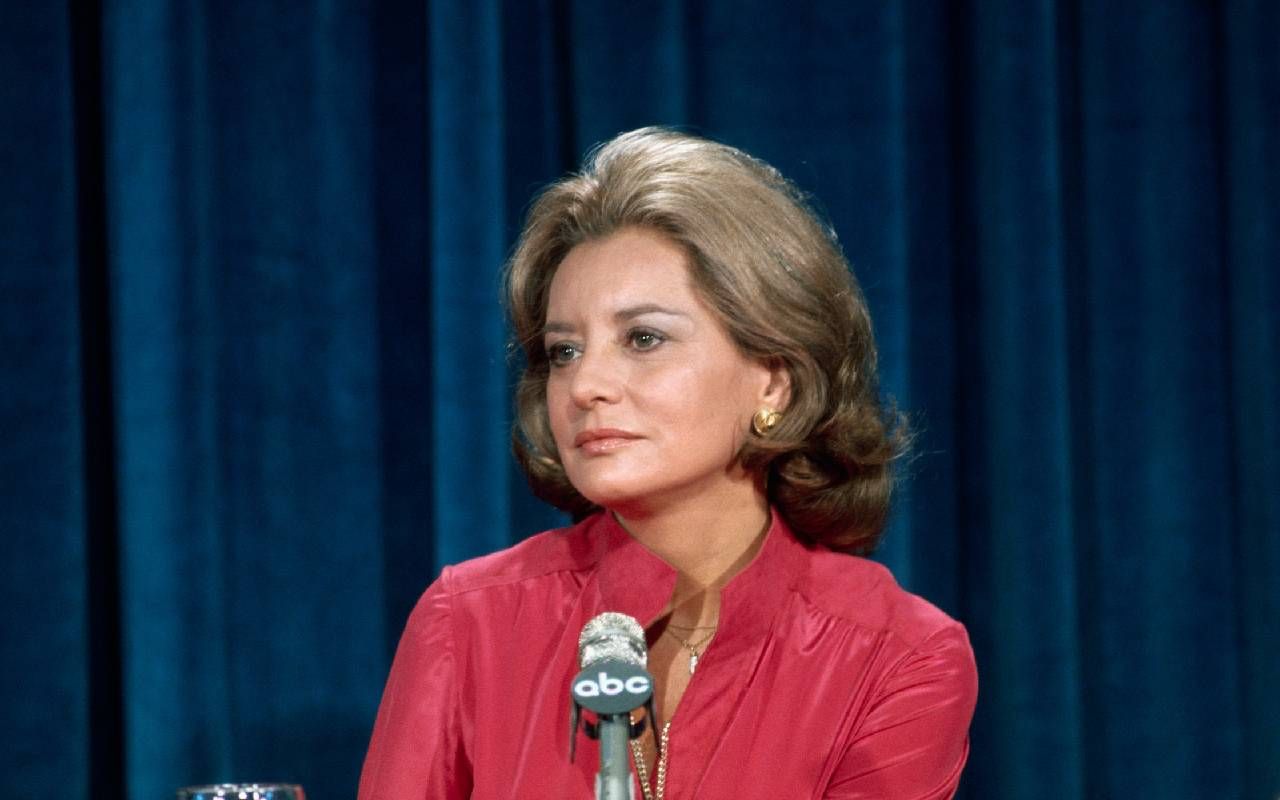

Nearly fifty years ago, it was a huge media story, a bombshell really. Tucked in the corner of the front page of the New York Times on April 21, 1976, ABC News had just offered Barbara Walters a million dollars a year for five years. It was a television news salary unheard of to that point, for a man or woman. It wasn't just the money that was historic. Walters would also be the first woman to regularly co-anchor the "Evening News" over a major television network.

But for Walters, there was no shortage of derision, especially from the men, like Harry Reasoner, her sourpuss co-anchor. He clearly didn't want to share the studio with anyone else, especially a woman. Gritting his teeth, he co-anchored with Walters for the next two years until he left ABC.

"She just powered through every person who told her what she couldn't do, an example for us all. She carried the scars to show it, too."

Barbara Walters, a groundbreaking journalist left her job at the "Today Show" at NBC to join ABC and immediately faced ridiculing headlines in some newspapers. Take the Miami Herald, for example: "Barbara Walters: Million-Dollar Baby?" Or the chauvinist comments of people like Richard Salant, the President of CBS News, who asked, "Is Barbara a journalist or is she Cher?" And just days after the news broke of the million-dollar offer to Walters, "Saturday Night Live" introduced the Baba Wawa character that would torment her and would be a staple of the comedy show for the next four decades.

Walters' news-making interviews — Monica Lewinsky smashed the ratings record — with world leaders and entertainment figures are just part of her legacy. In May 2014, Walters appeared on her last broadcast of "The View," the late morning broadcast she co-founded. She was greeted by a procession of more than two dozen female broadcasters led by Oprah Winfrey who declared, "We proudly stand on your shoulders, Barbara Walters." And as she gestured to the high-powered women surrounding her, she said, "I just want to say, this is my legacy. These are my legacy."

Susan Page, Washington Bureau Chief for USA Today, has written "The Rulebreaker: The Life and Times of Barbara Walters" out this week. The conversation has been lightly edited.

Next Avenue: Why a book on Barbara Walters?

Susan Page: Every woman in journalism owes Barbara Walters a debt. That includes me, too. She just powered through every person who told her what she couldn't do, an example for us all. She carried the scars to show it, too. Yet there was no serious biography of her. I thought, how could that be? And I wanted to write it when there were still dozens of people around who had worked with her — and competed against her – and could help tell her story.

By the time Walters died 16 months ago, she was more or less a recluse, and seeing only her caretakers.

I went into this project knowing I was very unlikely to be able to talk to her. And I didn't know her. And that was one of the reservations I had about doing this because for my previous two biographies, I had done extensive interviews with First Lady Barbara Bush and then with House Speaker Nancy Pelosi. So this presented some special challenges. PR representative Cindi Berger who's very close with Barbara talked to her about it.

It's not an authorized biography. It was a journalism project. But Barbara Walters didn't tell people, "Don't talk to her." And for that, I'm grateful that people could make their own decisions about whether they wanted to talk.

But, you know, Richard, what made it okay? I was the beneficiary of 1 million interviews about her life she had done from the time she was just starting out in television. There were profiles written about her. She lived life out loud.

"She lived life out loud."

After falling on the stairs at the British Embassy in 2013, you write it started a long decline and injury to Walters' brain.

Barbara's spokespeople kind of downplayed the seriousness of it. In fact, I found in doing the reporting, it was quite a serious injury that had enormous repercussions over the years that followed — brain issues associated with cognitive decline that contributed to a loss of mobility.

So by the time I began this book, she was in and out, as some older people are, and living a life of some isolation. As her health declined, she pushed away even many of her closest friends, and she was very concerned that the paparazzi not get a picture of her — which they did not — in her wheelchair. It meant she lived the final years of life, basically in her fabulous Fifth Avenue apartment with caregivers and her chief of staff, and just a very, very few people that she was willing to see.

You talked with dozens of people who knew Walters well. What was the one question you would have asked Barbara if you had the chance?

That's such a great question because of course, she was so great at crafting exactly the question that everybody wanted to hear the answer to. Here's a question I posed to almost everyone I interviewed, and maybe this is what I would have asked Barbara too. She is a woman of enormous achievements, of great consequence, enormous amounts of money, fame and groundbreaking things. But she had a difficult personal life, three failed marriages, a daughter, Jackie, whom she was estranged from for a time, but eventually reconciled. Never a sense of contentment. So I asked a hundred people this question: Was she happy?

Was she?

A couple of people said yes, but I've got to say 95% of the people who knew her said, you know, she was proud of what she did. She took joy in the work. But was she happy? No.

When Harry Reasoner told Barbara Walters at the end of their first co-anchored newscast, 'You owe me four minutes,' he was dead serious. They never got along, did they?

No. He threatened to quit when they told him that they were going to hire her to co-anchor the news, and then they gave him a big raise and he decided not to quit. But he made a private arrangement that he could leave, despite his contract, if he was really unhappy, which turned out to be the case.

He had pushed Howard K Smith away as a co-anchor. He wanted to be on the air by himself, but he had a special, sexist attitude toward women in general. And so, resentment at Barbara Walters. She thought about quitting. Instead, for nearly two years she waged what became a war of attrition against Reasoner, one that would damage both of their careers, at least for a time. Reasoner was quite the wordsmith in some ways. But if you read his columns in today's context, they would have gotten him fired. He wrote a column that said that he thought that flight attendants or stewardesses should be light and fluffy and basically entertaining, and then they should go away. Now, no one could have been less light and fluffy than Barbara Walters.

"No one could have been less light and fluffy than Barbara Walters."

Beyond Reasoner's bullying, a powerful Senator John Pastore, Democratic Chairman of a Communications Subcommittee, said at the time, 'It's ridiculous. The networks come before my committee and shed crocodile tears and complain about their profits. Then they pay this little girl a million dollars. That's five times better than the president of the United States makes.' This little girl!

Barbara was 47 years old at that time. She had spent more than a decade at the height of TV journalism. She was also someone who was supporting her father, her unhappy mother and her disabled sister. I mean, this was no little girl, but that is the kind of dismissal that she dealt with all the time.

As you write in 'Rulebreaker,' Barbara Walters had only started her journey on the road to being somebody when she made this declaration of intent in 1972: 'It's no fun being nobody, not having enough money to enjoy life, being trapped. It's wonderful to be somebody.'

Was that Barbara's main mission in life: to be somebody? Or is that too simplistic?

I actually think there was a pivot point in her life when she was 48 years old. She was kind of aimless. She had just gotten divorced from her first of three husbands. Her mother called on a Saturday morning and said that her father had swallowed all his sleeping pills in an attempted suicide; and I think, notable that her mother did not call an ambulance. She called Barbara, who ran over to the hotel with her parents. Barbara called the ambulance, and rode in the ambulance to the hospital. And at that moment, almost instantly, Barbara understood that the care and support of this family was now going to fall on her. It was at that point that she got serious about a career that she began to work harder than anybody else.

She had this relentless drive that she showed the rest of her life. Her father, Lou Walters, was an enormously successful impresario, founder of the famous Latin Quarter. He would make $1 million and then gambled it all away. So, during her childhood, they would be rich, and poor in a flash. I think that instilled in Barbara a belief that you could never be confident that everything was going to be okay. You could lose everything in an instant. And that meant that there was never a moment that she could sit back, relax, revel in all that she had done. She had to just keep pushing. I think Barbara was chased by demons.

"She continued to feel competitive with other women broadcasters even if she was the most well-established, most iconic woman broadcaster of their lives."

Barbara subbed for Ted Koppel during my time at "Nightline." The main difference between the two anchors — Ted didn't write down any interview questions, saying it's more of a conversation. But when Barbara came to the show, she enlisted some of the staff to brainstorm questions with her. My boss [executive producer] Tom Bettag reminded me Barbara always came in and seemed to sit under a tree and then she shook the tree to make sure none of the branches fell off. Tom would say that degree of self-knowledge, that hard news was not her specialty, was very impressive.

At one point, Barbara, Ted Koppel and Sam Donaldson called themselves The Three Musketeers. When Barbara encountered trouble as the co-anchor of the "Evening News" and was really in some professional distress, she did some White House coverage with Sam, and Ted was also involved. She didn't get along with everybody but she got along with Sam and Ted.

Barbara's friend and colleague Cynthia McFadden's standard line to Barbara was: 'If you could appreciate your success as much as the rest of us have benefitted from it.' But she wasn't able to do that. Why?

She didn't tie her success to make things better for women who followed. She pursued her career to pursue for herself. She continued to feel competitive with other women broadcasters even if she was the most well-established, most iconic woman broadcaster of their lives. It's part of her never being content or feeling entirely secure. It's just the thing that bedeviled her to the end of her days.

The constant harping on Barbara's speech anomaly that kept the "Saturday Night Live" caricature going for 40 years must have been annoying for Barbara.

Barbara was wounded by the SNL caricature. But when she did an interview with Bette Davis, whose most famous line was "What a dump!," she said to Barbara, you should be really glad you're being caricatured because it means you've succeeded in becoming iconic. That was of some comfort to Barbara. When Gilda Radner, who was the first to spoof Barbara on SNL, died young, Barbara wrote a sympathy note to her widower Gene Wilder, expressing sorrow. You know how she signed it? Baba Wawa.

Walters' second husband Lee Gruber once joked with Barbara that her grave marker should reflect her constant indecision. His suggestion: "On the other hand, maybe I should have lived." You not only found out where Barbara Walters was buried in the Miami cemetery, you also learned that her grave marker is distinctly different from her father's, mother's and sister's.

I figured that Barbara would've been buried next to her sister at a cemetery in Miami. But I had to finally hire a researcher to case the joint to try to find the burial site, which had been so private to even some of her closest friends who didn't know exactly where it was and what it said on her marker.

They all had these small grave markers. And the ones for the other family members say "beloved father," "beloved mother," "beloved sister" and the one for Barbara Walters says simply: "NO REGRETS. I HAD A GREAT LIFE."

And I guarantee you that Barbara Walters is the one who wrote that.