Linda Ronstadt on Preserving Her Culture

In an exclusive interview, she talks about helping Mexican youth discover their roots

During her four-decade-long career, singer Linda Ronstadt seems to have covered it all: country, rock and roll, pop, jazz, opera, Broadway standards, big band and songs influenced by Mexican and Afro-Cuban Cultures. She was awarded 10 Grammys as well as the National Medal of Arts, and membership in the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame.

Not only was Ronstadt successful with solo performances, she recorded chart-hitting duets with many singers including James Ingram and Aaron Neville. With Dolly Parton and Emmylou Harris, she formed the group Trio, which released two albums.

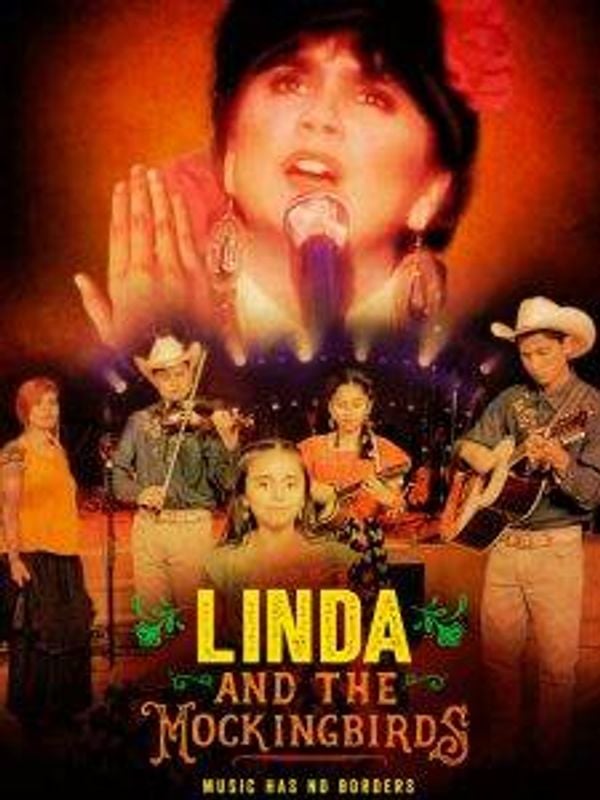

Although she retired from singing in 2011 due to health reasons, Ronstadt has stayed busy. A recent project is the documentary "Linda and the Mockingbirds," which chronicles her 2019 trip to Mexico with students from Los Cenzontles Cultural Arts Academy in San Pablo, Calif.

From her home in San Francisco, Ronstadt spoke with Next Avenue about the trip, the importance of preserving her Mexican-American culture and what she's up to now. The following interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Next Avenue: Why did you want this documentary to be made?

Linda Ronstadt: It came about purely by accident. I was taking a trip to Mexico with thirty kids, ages seven to nineteen, who are with this cultural group that I work with called Los Cenzontles. They take dancing, singing, instruments and visual arts in Mexican culture. They make videos of their own to document their trips.

Another couple of people were making a documentary about me. I said, 'If you want to interview me, you have to come to Mexico.'

And they said, of course, you're Linda Ronstadt. We'll go wherever to film you.

It was more interesting than filming me in the living room as a talking head. I think they saw the value in that.

But because they wanted to bring a film crew and we wanted to bring a film crew, it was crowded on the bus so I said, 'Let's just take one film crew and share it.' But then director James Keach decided he wanted to take over the Cenzontles film documentary. He liked it, and we wanted to do that, too, so it just came about very organically.

You've been a patron of Los Cenzontles Cultural Arts Academy for twenty-six years now. How did you get involved with them?

I was walking along the street, and they were playing on the sidewalk for change. I heard them, and they were really good. They were playing a regional haka [dance], and in Mexico, if you go across the street you have a different rhythm culture, different art, different everything.

Really?

Oh, it's so regional, and the regions are very close together. I think there might be thirty different languages that they speak in Mexico. I know they have thirty different languages in Guatemala.

"It's important for them to know that their heritage is rich in cultural treasures — like music and poetry, and dance — and that those things are not necessarily just for performance."

So, they were singing both in Spanish and in one of the indigenous languages, and I know those styles and those traditions. They were really authentic. I said, 'Where did these people come from?' thinking they'd come up from Mexico. They were in the East Bay.

They were trying to get enough money to make a trip to Mexico to this certain region where they found these masters of different kinds of music that they're studying. They wanted to take the kids there and see where it came from. So, I said, 'I'll give you some money,' so I added another concert. I was having my tour then of my Mexican show, so I added a show and gave them the proceeds from it, and they were able to go.

I love to go over there [Los Cenzontles] because I learn so much from the kids, you know. I talked to the ambassador for Mexico to the United States and she said she saw them and she said, 'There's stuff that we're not even playing in Mexico anymore.' Los Cenzontles are the only ones that are playing it, and they feel like they've really become this preserver of cultural treasures.

Why was it important for these kids to make this trip?

It's important for them to know that their heritage is rich in cultural treasures — like music and poetry, and dance — and that those things are not necessarily just for performance. They're for social interaction and processing your own feelings and reclaiming who you are with dignity, precision and musical ability.

Those kids don't have to audition to get in there. They're not pre-selected for talent. They figure that everybody can play and sing if you're taught right. Of course, they're right. They play it right.

A ten-year-old doesn't play necessarily as well as the symphony player, but they play the music right, and so it works. They learn rules of traditional music carefully, and they work on it for years. But after they learn the rules, they can break them if they want to.

What do you hope they learned from that trip?

Most of them are not from northern Mexico, so they learned about it, and it's its own little domain. It has a lot of influence from Indian, French and German people. It's a real mixed bag.

"Sometimes, we'd go to somebody's wedding, somebody's ball or somebody's picnic. Picnics were the best."

My family were German and Mexican. My great-grandfather married a Mexican woman whose family had been there since the 1670s. The Sonoran Desert is one region that happens to have a border fence through it at this point, but for centuries it didn't — and we were very happy without the fence.

I remember going to lunch with my family in Nogales, which is the border city sixty miles from Tucson. We'd go have lunch with friends and then we'd go shopping because they had fabulous stores. They had beautiful things that were handmade and imported from all different regions in Mexico. Sometimes, we'd go to somebody's wedding, somebody's ball or somebody's picnic. Picnics were the best.

We had a great time, and my dad would visit with all of northern Mexico. He owned the hardware store that supplied all the ranches, and he helped the people in the city, so it was a very urban-rural combination place. The food was divine.

My grandfather was born in a little town called Banámichi, on the Sonora River Valley, and they have the richest soil in Mexico. They've farmed in the same land for a thousand years. They farmed with irrigation techniques that the Indians developed that are completely sustainable.

Wow.

We built these two strips of alluvial soil down on the side of the river that's just like Egypt. In the middle of the harshest most unforgiving desert, there's miles of this green snake going down through the valley between the mountains. A lot of their farmlands are communally held, so they live together in a village, and they work the land in a cooperative way, so the culture is advisal and congenial and smart because they've refined these abilities over the centuries.

How long was the trip with Los Cenzontles?

About four days.

You all did a lot in four days.

It was amazing. They were so interested in everything. They danced, sang so beautifully and played. They got to meet a group of semiprofessionals, a regional dance group that won all of the national contests in Mexico. But they were a performance group with a different pedagogy. They throw their skirts higher, and they're more decked-out. But the kids that we took down there played their own music.

The performing group danced to recorded music because they had to dance to a lot of different regions and they couldn't afford to have all the bands there all the time to rehearse. But there's something about the dancers dancing to live music, the music responding to the dancers and the dancers responding to the music that is more special.

When you recorded the album 'Canciones de Mi Padre,' you told the public about your Mexican-American heritage, you toured with the album and you paved the way for so many others today. And you just received the Legend Award from the Hispanic Heritage Foundation. Do you see yourself as a trailblazer?

I didn't at the time. There were groups like Los Tigres del Norte, who can outsell The Rolling Stones in any country, but American/Anglo audiences haven't heard of them — even though they're the biggest group in the world. There have been groups like that, but they just weren't noticed in Anglo communities.

Mexican music tends to be dismissed like this is something you have in the background while you eat guacamole.

Why is it dismissed?

Because Mexican culture tends to be dismissed, even though it's had a profound effect on American culture.

Just the tiniest example is the cowboy suit, which comes from Mexican culture. Mexican food is the fastest-growing food culture in the world. Everybody knows what a taco is and everybody knows what a burrito is, but they don't know anything about the persons responsible for inventing it. And they don't know the best way to eat them either, which is in Sonora where they make the big, white-wheat tortillas by hand. They make it with an old variety of wheat, and they make it with lard and salt and it's so delicious. They bake it on a griddle over the fire.

That's what I grew up eating — it's completely different from a commercial tortilla that you buy.

What do you think about the push to involve people of diversity throughout all types of media? Why is it so important?

Because otherwise people are marginalized. The group that's been marginalized probably the most are the Native Americans — and the ones from California the most critically. There's no excuse for it. It's ignorance.

They wouldn't teach the history of slavery in the schoolbooks. I had to learn about how horribly slaves were treated. In the schoolbooks, they said, 'Oh, some people were nice to their slaves.' How do you be nice to a slave? The condition of the enslaved person is not nice to start with.

Fifteen years ago, I read that history, and I was just stunned that people were tortured through basically a reign of terror for four hundred years. When it stopped being slavery, it started being Jim Crow. And when it stopped being Jim Crow, it started being putting everybody in prison forever.

It's just one continuous spread. It has to stop. We're going to have a race war if it doesn't.

I think we're going to have a civil war. I don't think there's any way around it. Race will be drawn into it. It'll be a cultural war, but race will be drawn into it as it always is. It's always bad results.

You were originally diagnosed with Parkinson's disease, but now doctors have said that you actually have progressive supranuclear palsy. Is that correct?

Yeah, that's right. It's a form of Parkinson's, and it's really easy for it to be misdiagnosed as regular Parkinson's disease. But it's a little bit different. For instance, it doesn't respond to any Parkinson's medicines.

Because of it, you can't sing. But has anything changed for you in a positive way because of what you've experienced?

I get to stay home and read all the time. That's pretty good.

Unfortunately, eye problems come along with the disease. But I'm still able to read, so that's a good thing.

I'm a homebody, basically, and I've traveled a lot of places. I don't need to travel so much anymore. It's very difficult to travel and to go out, so I pick my occasions like going out to the opera. But I can't do that now.

"I loved singing with the duet partners I've had. Singing with Aaron Neville is like being in heaven singing with an archangel."

And I'm hoping that by the time the pandemic is over, I am still able. But the disease takes away a lot of things. I like to knit and I like to sew and I like to embroider, and I can't do any of those things anymore.

There's nothing to do but accept it. No use fighting it and arguing with it.

What message do you hope that viewers who watch this documentary get out of it?

I hope they understand that dehumanizing an entire group of people who are humans is a losing proposition. It deprives us of the richness of their culture and of their ability to incorporate into the mainstream of our culture. We're losing the gifts they can give us, and besides, it's mean.

I agree. Last question: Regarding the duets that you sang, do you have a favorite?

I did my best signing on a duet with Frank Sinatra, but it was really hard to sing a duet with him. His voice was in sort of rocky shape, but he was still dangerous. I had to figure out a way to slide around him and make it work. I was really pleased with the way it came out.

I loved singing with the duet partners I've had. Singing with Aaron Neville is like being in heaven singing with an archangel. I learned so much singing with him.

I probably learned the most from singing with Emmylou Harris. She taught me a great deal at a time when I really needed to learn it.

And John David Souther — I was really happy singing with him, too.

"Linda and the Mockingbirds" will be released digitally on Tuesday, October 20.