Morphine: A Misunderstood Medication

Physicians and caregivers work to clear up myths about powerful end-of-life drugs

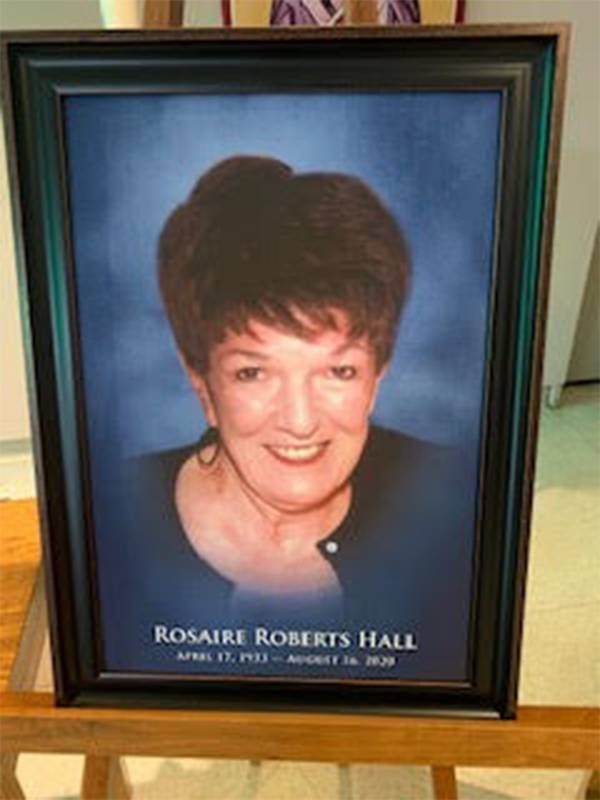

Within weeks of being diagnosed with multiple myeloma at 87, it became clear that Rosaire Roberts Hall was at the end of her life. Last summer, she moved from her lake house in the woods of northern Minnesota to a hospice home that was nearer to her family.

"The disease took off fast, but she was still sharing memories at the end. We sat together and she told stories I'd never heard," said her granddaughter Heather Kern, of St. Cloud, Minn.

Hall lived a big life, not just a long one.

"It would have been horrible to see her suffering. What we had with her right until the end was quality time. It was a real blessing."

Raised in an affluent family in suburban Detroit, she entered the Dominican Sisters' Congregation after high school. As a Catholic nun, she became a school principal and a Mother Superior. After 25 years, she was dispensed from religious vows and went on to marry a Minnesota businessman, adopt his four children and become a college professor.

The type of cancer that Hall developed can cause severe bone pain. Her doctors used morphine to manage it.

"They found the right dose. She wasn't sedated too much; she could talk to us and we shared memories," Kern said. "We had good communication from the whole team."

Being with a loved one as their days wind down can be a painful, profound and poignant experience for family members. Their sorrow can be compounded by confusion and fear about the heavy-duty narcotics that are routinely administered to keep the dying patient comfortable.

Physicians and others who work in hospice want to lift the veil on end-of-life medications to better prepare patients and families for their use. These drugs are widely considered helpful in managing pain and facilitating the so-called "good death" that hospice offers.

"The goal of hospice is to improve life at the end of life. Good pain-symptom management is one of the most primal things people want then. Morphine and strong opioids are key tools we have to make that happen," said Dr. Joseph Shega, executive vice president and chief medical officer for VITAS Healthcare, the nation's largest single-source provider of end-of-life care.

Hospice professionals say that in an ideal situation, the patient, their family and their health care providers have time to meet to discuss the plan for the patient's final days, complete with a conversation about the goals and expectations of morphine in managing pain.

"We try to be more proactive than reactive, to overcome some of the preconceptions people have about the use of morphine. Many families worry that if their loved one takes morphine, it will shorten their life," said Shega. "We explain that we start morphine at the lowest dose possible so that people stay awake, alert and have good symptom and pain management. Our goal is to neither accelerate nor prolong the dying process."

That said, there have been anecdotal cases where hospice workers or doctors have subtly let family members know that if they say a patient is in too much pain, the morphine dosage can be increased, hastening the death.

Comfort Care

In hospice, the focus of care shifts from pursuing cures and treatment in favor of medical support that emphasizes comfort.

In the past four decades, the hospice movement has gone mainstream for patients who have a terminal condition. An analysis by the National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization, tracked a steady rise in the number of patients choosing this kind of care. Its most recent survey showed 1.5 million Medicare recipients were enrolled in hospice in 2018.

"Unfortunately, people don't think much about dying until the end is very near. If the situation gets out of hand, they are unprepared. The more planning people do, the better off things are."

But being with a loved one as death approaches remains an experience that most people are unfamiliar with. They may misunderstand the value of drugs they have heard described as dangerous.

"Patients may have a plan they've discussed with family, but end-of-life opioid use is seldom part of it," said Arun Vijay, a Seattle physician who is board-certified in hospice and palliative medicine. "They may all have assumptions and opinions associating these drugs with addiction. But that should not be a concern in hospice."

According to statistics compiled by the national hospice group, more Americans want to breathe their last in a familiar setting. Half of all hospice patients now die at home while being attended to by hospice medical professionals; the other half die in assisted living, nursing homes, hospitals and hospice facilities.

Sometimes family caregivers who are on duty with loved ones in the home are given so-called comfort kits, a package of medications they can administer when they observe a change in symptoms when a nurse or doctor is not present.

"They consist of several medications to help with symptoms — diuretics, drugs to help with nausea, shortness of breath and fluids in the lungs, and concentrated morphine for pain," said Kevin Truong, a pharmacist based in Seattle. "The drugs are in small doses and meant to help get through a time until the provider can get to the patient."

Seeking Support

Hospice professionals find that the active-dying process typically lasts less than a week, but the end can be excruciating for some at the bedside.

Hospice clinicians report that family members, distraught in a loved one's final days, have been known to request that the dose of morphine be upped to speed the process.

"They will ask if providers can move it along and the answer is no. If a family member says, let's make this happen, we explain that's not how hospice works. We want to keep the patients comfortable and not alter the timeline," said Vijay.

"This usually happens when the family is just exhausted," added Shega. "In hospice, we rely on an interdisciplinary team for psychological and spiritual needs. We can bring in social workers and chaplains for that additional support that acknowledges what they are going through."

Medication used at the end of life is defined differently in the nine states that have enacted death with dignity laws.

These states allow terminally ill adults to request prescription medication to hasten their imminent death. A waiting period is built into the process and two physicians must confirm the patient's diagnosis, prognosis and mental competence before writing prescriptions for life-ending medication.

"It's actually very hard to kill someone, even with very powerful medicines. Our systems are well designed to keep us alive," said Dr. Bob Wood, a retired internist and medical adviser at End of Life Washington.

"We think it is important to ask the client what a 'good death' is. They really ought to define it," he said. "A 'bad death' is someone who is going out in agony, dying without support and nothing for their pain and anxiety. Unfortunately, people don't think much about dying until the end is very near. If the situation gets out of hand, they are unprepared. The more planning people do, the better off things are," Wood added.

Quality Time

The call went out to a large number of Rosaire Roberts Hall's loved ones as her body slowed down, and three generations of loved ones arrived to say their final farewells.

Because of restrictions brought on by the pandemic, two loved ones could sit by her side for limited hours. A steady stream of children, grandchildren, great-grandchildren and their spouses gathered outside her window to wave, blow kisses and say goodbye through the screen.

"We could see how relaxed she was. They helped her get her sleep, so she was rested," said Kern. "It would have been horrible to see her suffering. What we had with her right until the end was quality time. It was a real blessing."